Highlights

With Jack Dorsey bowing out and Parag Agrawal taking over as CEO of Twitter, Indian immigrants now captain not just Twitter but many of the biggest companies in the tech sector, from Google to Microsoft. In a comment highlighted by many in the Indian press, Tesla CEO Elon Musk picked up on the trend in a Tweet that read, “USA benefits greatly from Indian talent!”

Indeed, Agrawal was born in Ajmer, a city in the Indian state of Rajasthan. He joins a growing list of American tech executives of Indian descent, including Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and IBM head Arvind Krishna.

One way to view the Indian American success in tech is simply as a matter of numbers. “If a dozen of the top CEOs in the world come from a country with 18% of the world’s population, why would I be surprised?” asked Seshadri Kumar recently.

But the Indian CEOs at the top of American tech companies are hardly the only example of Indian American success. Our analysis of data derived from the 2019 American Community Survey paints a picture of a group that has found astounding success in the United States in achieving what could be called the “Indian American Dream.”

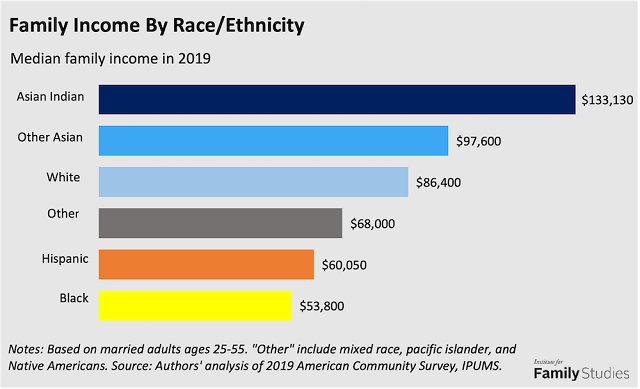

Indian immigrants make up about 6% of the U.S. foreign-born population and are now the second-largest immigrant group in the U.S., after immigrants from Mexico. As one example of their success, Indian Americans now top the charts in income. Median family income among Indian Americans between the ages of 25 and 55 was $133,130 in 2019, well above the white median income of $86,400. Indian Americans also have higher income than other Asian Americans. The median family incomes for Chinese, Japanese and Filipino Americans ages 25 to 55 were about $100,000 in 2019, well below Indian Americans’ median family income.

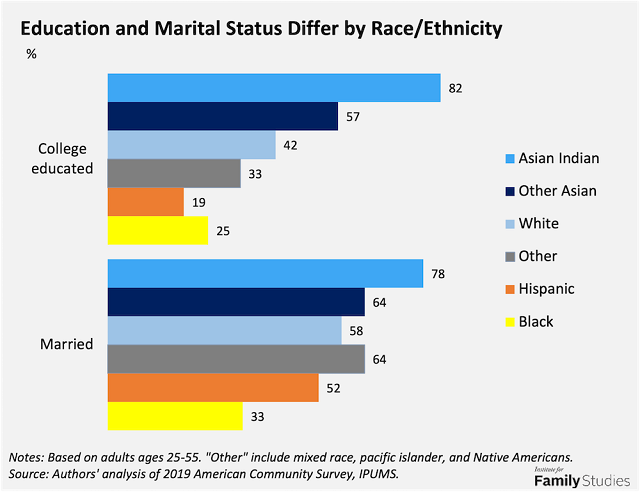

Two factors appear to play central roles in the rise of Indian Americans: education and family. No other racial group of Americans is as well educated as Indian Americans — 82% of Indian American adults ages 25-55 are college educated, compared to just 42% of whites who have a degree. Meanwhile, no other group of Americans is as likely to be married as Indian Americans — 78% of Indian Americans ages 25-55 are married compared to 58% of whites.

Indeed, both education and marriage help explain the income gap between Indian and white families. After controlling for education, the white-Indian gap in average family income shrinks from $61,868 to $36,628. When marital status is also controlled in a regression model, the gap falls to $28,410.

This would hardly come as a surprise to observers of Asian and immigrant cultures, including Indian American culture, which often place a special emphasis on both education and family.

Vimal Duggal, a retired Indian American who moved to the United States in his 40’s and brought his young children with him, explained how he raised his kids to see education as the path to prosperity. “Three years of hard work you do now (in high school), the rest of the life will be easy. You can enjoy life, then the rest of the life will be very hard for you. So, you decide what you want to do,” he said he told his kids about the dangers of slacking off on their studies.

Deepak Bedi, a Houston-area physician who was born and raised as an Indian in Kenya, explained that many Indian American families go above and beyond to educate their kids. “One of the keys that takes Indian kids far is that it’s not just what they learn at school. I think there’s schooling at home in addition to what goes on in schools,” he noted. “You might find a kid who’s 10 years old but is practicing math with their mother at home every day.”

This Indian American emphasis on education came through crystal clear in a study conducted in 2017 by the life insurance company Mass Mutual. The study of parents across America concluded that “Asian Indian parents consider a college education as the key to a child’s success, maturity, respect and the gateway to full employment — and woven into the fabric of Asian Indian culture is a parental obligation” to fully fund their kids’ education. The researchers noted that “by the time a child has reached the age of 10, 79% of Asian Indian parents, more than any other ethnic group in the study, are saving for college.” Moreover, 90% of Indian American parents, higher than any other ethnic group in the study, said that a college education was important.

The Indian Americans we spoke to for this piece emphasized that part of the reason first-generation Indian American parents push their children so hard is because they faced an uphill path into the American middle class.

“When you come to a different country, difficult culture, different society, you have to prove yourself. It’s not going to be easy for us to compete with … native, local residents because for them it’s easier. The path is easy. For us, it will be hard,” Duggal told us. “We have to get that edge, and the only way I think we can get that edge is by going to college and getting some … knowledge and experience and then training.”

Family, too, is a cornerstone of Indian American life. Our analysis of the 2019 American Community Survey finds that Indian immigrants have the highest family stability of any group in America, with 94% of Indian immigrants with children stably married, compared to 66% of white Americans. (Family stability is also higher for Indian immigrants than native-born Indian Americans — for whom 87% are stably married, still way higher than average, but not as high as what we see among the first generation.)

Part of the reason for the strength of the Indian family unit is the way Indian culture stresses familism over individualism.

“With family, it’s a very strong collective unit,” Pooja Mamidanna, a therapist who has spent years working with Indian American clients, told us. “You want to give back to your elders. You want to honor your family’s name, and you take care of your elders. … It’s not I vs. you. (It is a) collectivistic family dynamics that exists, it’s we come together first. So, it’s not even about putting yourself first. It’s putting your family first.”

Duggal stressed that he believed in raising his own children in a moderate way — avoiding being both too tough and too lax. But he also suggested that American parenting is too lax today. “They don’t push at all,” he said of many Americans parents. “They are completely laid back. …. Children need guidance. They don’t need dominance, but they need guidance. And this guidance part is missing in the mainstream (American culture), in my opinion.”

This is not to say traditional Indian American culture is not without its own challenges.

“Being hardworking, being raised in such a family system, it’s a blessing and a curse. It’s a blessing because it helps you achieve your goals, it gives you that drive, it gives you that ambition, but when it becomes slightly problematic is when the parents don’t really understand what that pressure can do to (the kids) in the long term,” Mamidanna noted, “With their identities, like having low self-esteem, having low confidence, or this need to always (be) perfect.”

For many of her younger clients, she needs to get parental buy-in to continue seeing them. But many of the parents she talks to are unsympathetic to their kids’ anxiety and stress. She deals with this by reframing the therapy to appeal to traditional Indian values.

“I had to change the language when I would talk to their parents, like tying it back to their academic success in school,” she noted. “Saying … they are struggling in school a little bit, and therapy would also give them the tools to like better perform in their academic life.”

But like many other groups of people who immigrated to the United States, successive generations of Indian Americans are joining the melting pot, fusing aspects of their homeland’s culture with America’s.

Unlike many other Indian Americans, Bedi didn’t try to pressure his children into joining the fields many Indians commonly enter, like STEM, and he also didn’t push them to get married young.

“They’re making their own decisions,” he admitted of his kids, who are in their 30s. “It sort of can make a parent unhappy at times, but I think we accepted that it’s their life. And I think that sometimes they are performing to a much lesser potential than they could have than if they had stayed on the same straight path as many other traditional Indians do here.”

But he thinks there are benefits of a more liberal approach, noting that Indian Americans are starting to diversify their interests and becoming better represented in fields like entertainment. Ultimately, this branching out may be the result of a generation of younger Indian American children who didn’t have to struggle the same way their parents did and can afford to pursue a less rigid path to achieving the Indian American Dream.

“I don’t think the Indian immigrants here … will become exactly like the locally born Americans in this aspect of achievement because that element of the achievement culture — I’ve got to study, I’ve got to get ahead — that’s already baked into the system, into the genes, if you will,” he said. “Even though I was a physician, I was in a system where I had to perform better than my peers to show them I was equal when I came here. I still had to do that for many years during my career. You had to be better than your local peers to be considered equal. So, I think when these kids were born here, they will never have to do that. They are considered equal in that sense just right from the start.”

The question, of course, is whether Indian Americans born and raised in the United States in coming generations will hold onto the educational and family advantages that have helped the first generation rise to the top of the American economy.

Zaid Jilani is a freelance journalist who previously worked for UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center. Brad Wilcox is director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies and a Deseret News contributor. Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies.

This article appeared first at Deseret News. It is reprinted here with permission.