Highlights

- The proposed universal child care plans should be seen for what they are: efforts to crowd-out family and informal child care in favor of a government-centered model. Post This

- A one-size-fits-all model of child care wouldn’t have worked for Senator Warren. And it won’t work for the rest of the country, either Post This

- Given a transparent price for child care, parents can—and do—make their own choice. Post This

Federally-funded universal child care is one of the most popular ideas on the Left right now. In February alone, three distinct proposals for universal child care were released, two from Senators Elizabeth Warren and Patty Murray, and one from Matt Bruenig of the People’s Policy Project.

While each proposal differs in important ways, they share a common vision of greater federal involvement in child care, regulations that mandate worker quality, and public financing to make formal child care centers either free or heavily subsidized. Left off the agenda is equal recognition of home- and family-based models that remain the dominant source of child care in the United States, and one that surveys show most parents prefer.

In addition, while framed as responding to a crisis of affordability, none of the above plans offer a strategy for addressing the root causes of rising child care costs, and, in the end, could actually exacerbate the affordability crisis. Instead, the plans should be seen for what they are: efforts to crowd-out family and informal child care in favor of a government-centered model. International experience suggests this comes with significant risks, both to the well-being of children and to the freedom of parents to choose a child care model that works best for them.

In what follows, I unpack the two main arguments cited in defense of universal child care—that it’s good for kids, and that it’s good for female labor force participation—and show that, compared to neutral child benefits, universal child care comes up short on both counts, while doing damage to the immense pluralism of American family life.

Is Universal Child Care Good For Kids?

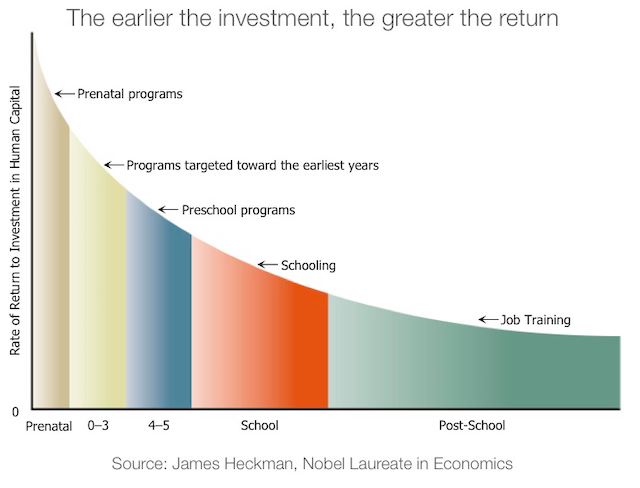

It’s impossible to delve into the child care debate without running into the name James Heckman, a Nobel prize-winning economist, famous for his work on human capital development and early childhood education. According to Heckman, “The highest rate of return in early childhood development comes from investing as early as possible, from birth through age five, in disadvantaged families.” This is shown in the famous Heckman Curve, a stylized representation of the return on human capital investments at different stages in life:

Consider the Perry Preschool program, a randomized controlled trial in 1970s Michigan that compared the life trajectories of 58 preschool-enrolled children to a control group of 65 children. Based on the improved life outcomes of children who attended preschool, researchers have estimated large “internal rates of return” on the initial childhood investment, ranging from 8% to 21 percent. Studies like these are the source for the often-heard claim that $1 spent on child care produces $8 for society, thereby paying for itself. But is this true?

What advocates neglect to mention is how much of an outlier the Perry Preschool program study and similar studies, like the Chicago Longitudinal Study, are compared to studies of comprehensive state- and nation-wide programs. In the Perry study, as much as two-thirds of the estimated benefits derive from lower rates of incarceration by age 40, thus capturing the unusually high cost of the U.S. criminal justice system. The mechanism appears to be the extraction of disadvantaged kids from high-crime neighborhoods and unstable households into comparatively benign social settings. In contrast, the Abecedarian Project in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, another ‘70s-era randomized study of disadvantaged children under five, found no effect from preschool on reduced criminality. Nonetheless, advocates routinely extrapolate inflated rates of return to universal child care when there’s no reason to think they generalize to the country as a whole. Indeed, a comprehensive study of Head Start, the federally funded and nationwide preschool program for poor children, found no significant effects on criminality.

But what about other effects, like on child cognitive and noncognitive skills? After the Canadian province of Quebec introduced universal day care in 2000, subsequent research found large, detrimental effects on child noncognitive development, including increased rates of criminality. A third of the children who entered the program came from family-based and informal care arrangements. In order to achieve universal scale, many of the kids who had their care arrangements displaced became victims of a “lowest-common denominator” effect.

Studies in the U.S. find positive effects from Head Start on long-run outcomes like educational attainment. However, the same line of research has reached the seemingly contradictory conclusion that the impact of early childhood education on test-scores is subject to rapid fade-out, disappearing after a year or two. Rather than “teaching young brains how to learn,” preschool appears beneficial for purely social reasons. In particular, Head Start frees up low-income parents from child care duties, allowing them to enter the workforce and pass on the associated benefits to their child later in life. While this lends support to the case for child benefits targeted to low-income households, it’s disastrous for the broader Heckman-inspired narrative. Indeed, it suggests the Heckman Curve should be flipped. Rather than supporting the human capital development of kids, at best, universal child care supports the human capital development of parents.

The Incomplete Labor Force Argument

This brings up the second defense of universal child care: increased female labor force participation. Jordan Weissmann recently made a strong version of this argument in a column for Slate, arguing that the high price of child care in America was “leaving GDP points on the table”:

One of the better arguments for providing child care services—as opposed to straight cash payments to parents, as some policy wonks have proposed—is that encouraging women to stay in the workforce will create future economic gains.

As the previous section showed, this argument has some merit. The question, of course, is whether universal child care is the best way to get there.

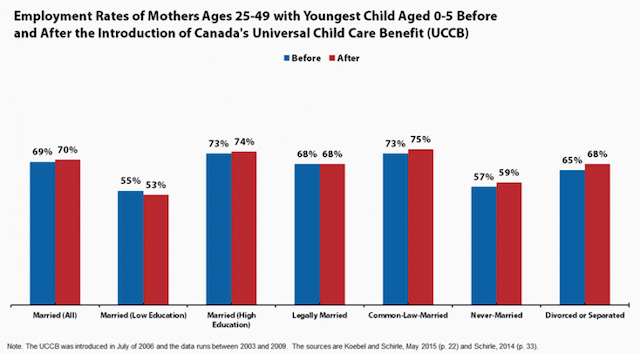

In my 2016 paper, "Toward a Universal Child Benefit," I argued that a fully refundable Child Tax Credit (i.e. a child allowance) would be able to meet the child care needs of parents while preserving family style choice. Weissman pooh-poohs cash payments, however, because they don’t foist maximal labor force participation onto parents. Yet after Canada enacted a national child allowance in 2006, employment rates for mothers actually increased across the board.

The one exception was married women with low education, and for obvious reasons. As I wrote in a 2017 report for the Niskanen Center,

The decision of whether to be a stay-at-home or working parent is a function of opportunity cost, which is, in turn, a function of education. Like it or not, it is often the case that parents who have a low level of formal education but who also have the support of a spouse are often the most cost-effective (and highest quality) provider of child care among the available options.

Importantly, low education is not the same as low income. For poor households, a child allowance that helps the parent afford child care as they attend school can boost their educational attainment and future earnings. Yet whether this is a cost-effective choice depends both on their preferences and on transparent pricing. Suppressing the price signal of market-rate child care through subsidies or direct public provision, in contrast, only serves to induce the use of formal child care by households where the opportunity cost doesn’t otherwise make sense. This destroys, not increases, GDP.

An Agenda for Child Care Pluralism

Canada doesn’t have a national child care program, yet it has a prime-age female employment rate that is nearly 6 percentage points higher than in the United States. Canada’s liberal regulation of home day care providers is partly to thank. Only one-third of Canadian children, age 4 and under, rely on formal day care centers, similar to the rate in the U.S. The remainder are cared for by private care like family (28%) and home day care (31%).

Home day care providers in Canada can open without a license below a certain threshold of children. In Ontario, the most populous province, the threshold is more than 2 children under the age of two or more than five children over the age of two (both including your own children under the age of six). Past this threshold, home day care providers are required to register with the province and meet provincial health and safety inspections. Licensed home day care workers are also required to pass a criminal record check and take first-aid training but are not required to obtain a “Registered Early Childhood Educator” designation.

Seen through the lens of the working parent, the pursuit of higher child care “quality”—be it in the form of stronger licensing requirements or mandatory curriculum standards—is actively counterproductive. Instead, child care choice and affordability can be tackled simultaneously by relaxing regulations on home and formal day care centers across the United States and, in urban areas, reducing restrictions on land use that push up the price of real estate.

With appropriate cash benefits to parents and a legal framework that opens up lower cost options, there is no argument for favoring universal child care outside of social engineering. Given a transparent price for child care, parents can—and do—make their own choice. Only 11% of Canadian parents cite affordability or the feeling that they only had one option as the reason behind their choice of child care. Many households simply prefer family and home-based child care, both for their proximity and because they know and trust the provider. Surveys of U.S. households express a similar preference.

Unlike other early childhood interventions, the positive impacts of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit on child outcomes are large and unambiguous. Given that a true child allowance would also be among the most cost-effective anti-poverty programs possible, its prioritization in the U.S. debate should be a no-brainer. The only contemporary proposal that comes close to this reality is the American Family Act, sponsored by Senators Michael Bennet and Sherrod Brown. It would transform the existing Child Tax Credit into a monthly child allowance of $300 per month for children under 6 and $250 per month for children under 17. On its own, this would cover about 75% of the cost of full-time child care in a low-cost state like Mississippi. Importantly, it would also preserve the incentive for more expensive states to address affordability through real reform, rather than have the costs of their excessive regulation propped-up by federal grants.

Conclusion

In the essay introducing her universal child care proposal, Senator Warren opens with a story from early in her academic career:

One day I picked up my son Alex from daycare and found that he had been left in a dirty diaper for who knows how long. I was upset with the daycare but, more than anything, angry with myself for failing my baby. At the end of my rope, I called my 78-year-old Aunt Bee in Oklahoma and broke down, telling her between tears that I couldn’t make it work and had to quit my job. Then Aunt Bee said eleven words that changed my life forever: “I can’t get there tomorrow, but I can come on Thursday.” Two days later, she arrived at the airport with seven suitcases and a Pekingese named Buddy—and stayed for 16 years.

Senator Warren never expresses any regret for enlisting her Aunt Bee. Something tells me that she, like millions of Americans, preferred the care of a loving family member over that of a stranger, credentialed or not. I suspect Aunt Bee enjoyed her time as well, finding new meaning and purpose long into retirement.

Of course, not everyone has an Aunt Bee to call upon. But that’s simply a reminder of the immense diversity of life in America, spanning families large and small—parents with promising careers and others who find fulfillment nurturing their family. While the debate around universal child care can often sound technocratic—“internal rates of return” and GDP figures abound—it’s important to remember the pluralism beneath it all. A one-size-fits-all model of child care wouldn’t have worked for Senator Warren. And it won’t work for the rest of the country, either.

Samuel Hammond (@hamandcheese) is the director of Poverty and Welfare Policy for the Niskanen Center.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.