Highlights

Americans are having less sex. Demographer Jean Twenge has found that adults today have sex about nine fewer times annually than in the 1990s. Twenty-two percent of adults reported having no sex in 2016, compared to 18% in the late 1990s. This is in large part because Millennials have less sex than both their parents and grandparents did at the same age. Gen. Z looks to be even less active: the CDC has found that just 40% of high schoolers have ever had sex, down from 54% in 1991.

This decline—especially among young people—is what a recent Atlantic cover story labeled the “sex recession.” In that essay, Atlantic senior editor Kate Julian does an admirable job of reviewing a whole host of changing behaviors—increased porn use and masturbation, achievement-oriented culture, rising depression and concurrent anti-depressant use, etc.—that might explain why Americans do “it” less.

But there is one major factor to which Julian only gives passing attention: marriage. Americans have conspicuously transitioned en masse from a more sexually active group—married people—to a less sexually active one—the unmarried. Any talk of a “sex recession” must acknowledge this marriage stagnation.

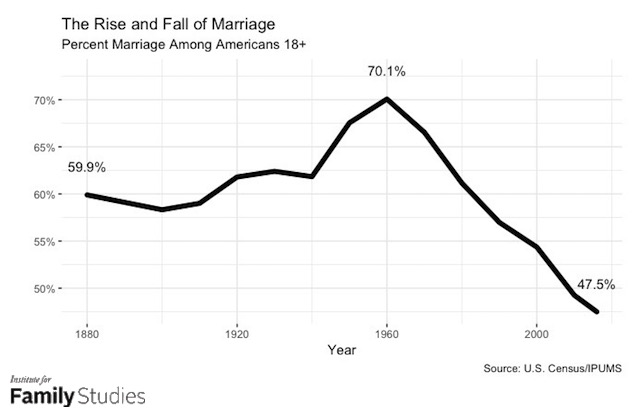

Today, there are fewer Americans married, and more Americans single, than at any point in at least the past 140 years. As the figure below illustrates, Census data show that the married proportion peaked in 1960, driven by surging marriage rates after the end of World War II.

From the 1960s onwards, however, there was a stunning reversal. From a post-war high of nearly three-quarters of the population, the married proportion has fallen by 22 percentage points. Today, only a minority of Americans are married.

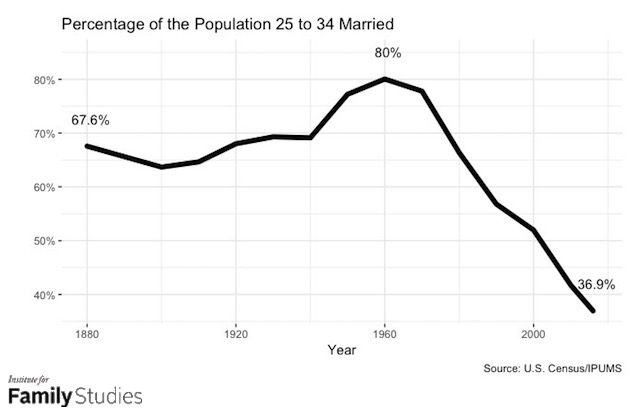

The effect is even more pronounced among young adults—the people for whom the sex drop is most concerning. Americans are of course getting married later, but even looking at those aged 25 to 34—solidly out of college and into adulthood—we find that more than 80% were married in 1960, and less than half as many are married today.

This shift has major implications for the frequency with which Americans have sex. That’s for one simple reason: as Twenge writes, “married people have sex more often on average than unmarried people.”

It is not hard to imagine why. Television’s depiction notwithstanding, the single life is filled with barriers to sex. Ceteris paribus, any two single people potentially interested in coitus have less reason to trust one another, have less ground for shared emotional intimacy, and less steady “access” to one another as compared to a married couple. For millennia, the great appeal of marriage to many has been that it generally provides consistent access to at least some sex.

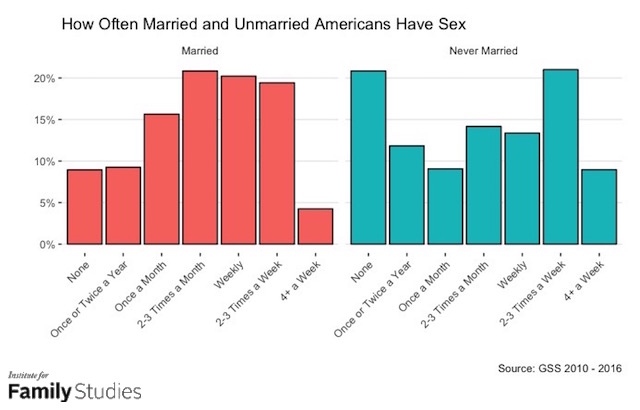

What was true a thousand years ago is true now. We know this from the General Social Survey, which polls respondents on the frequency with which they have sex. The distribution of sex among the married is roughly bell-shaped: some have a little, some have a lot, but most have at least some. The mode frequency is two to three times a month.

The distribution of the never-married population, by contrast, is inverted. It is possible to have a lot of sex while not being married, but it is just as possible to have no sex at all. And most of the “in-between” categories—sex one to four times a month—are far less prevalent among the never married.

This all implies that the distribution of sex among the married is far more equitable than among the unmarried. Copulating while single is a crapshoot, with the population composed of haves and have-nots. But most people who are married have sex — married men and women alike get at least a little. A mass transition of the population from one group to another thus explains a lot about why there are more “have nots” overall.

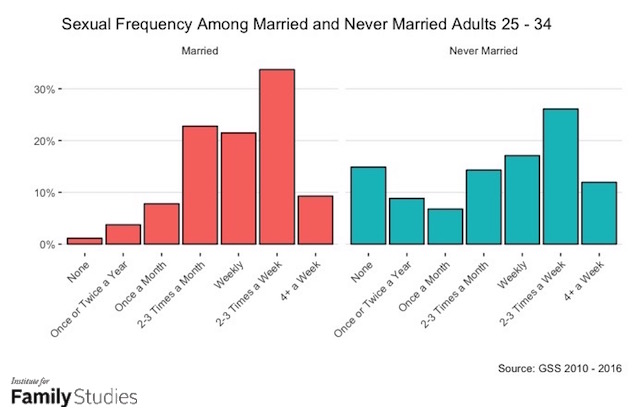

Zooming in on young adults tells a related story. In general, they have a lot of sex—the modal frequency is two to three times a week for married and unmarried alike. But essentially zero married 25- to 34-year-olds are sexless, while a sizable proportion of the young unwed have sex once a year or less.

In other words, if there is a glut of young people who don’t have sex, that group is overwhelmingly clustered among the unmarried. The implication is that those people are sexless in no small part because they are not participating in humans’ most reliable avenue to sex.

Importantly, declining marriage doesn’t totally explain the sex recession. As Nicholas Wolfinger has written for IFS, there’s been a significant drop in sex among married people. Why is an open question; labor force drop out, declining testosterone, and the allure of electronic distractions could all play a role. Still, the within-marriage sex decline is far less pronounced than the great shift of Americans, especially young Americans, from wedding vows to bachelorhood.

There is no monocausal explanation for why marriage has dropped—shifts in culture, economics, and politics all play a role. What we can say is that Julian is probably right: dating apps, widespread porn use, and the eroticization of popular culture have not made Americans more likely to have sex. If America wants to reverse this—and reap all the rewards that come with a robust sex life—then maybe it’s time to think about making it easier, and more popular, to get hitched

Charles Fain Lehman is a staff writer for the Washington Free Beacon, where he covers crime, law, drugs, immigration, and social issues. Reach him on twitter @CharlesFLehman.