Highlights

- We take another look at adopted children's academic and behavioral outcomes in response to reader questions. Post This

- Foreign-born adoptees were less likely than U.S.-born adoptees to have their parents contacted due to classroom behavior problems, although the significance level of the difference was only marginal. Post This

Adopted children are more likely to struggle in school—both in terms of academics and behavior—than children from other types of families. This was the takeaway from our most recent post on adoption, and it is surprising because adoptive families tend to be more affluent, educated, and stable than other American families. The post garnered a good deal of attention and a number of important questions. We deemed the following two questions especially important and have sought to answer them with some of the data at our disposal.

1. In your most recent post, you compared all adoptive children to children being raised in intact, biological families. That means you did not compare adoptive children in intact, married families to biological children in intact, married families? When you do this, what do you find?

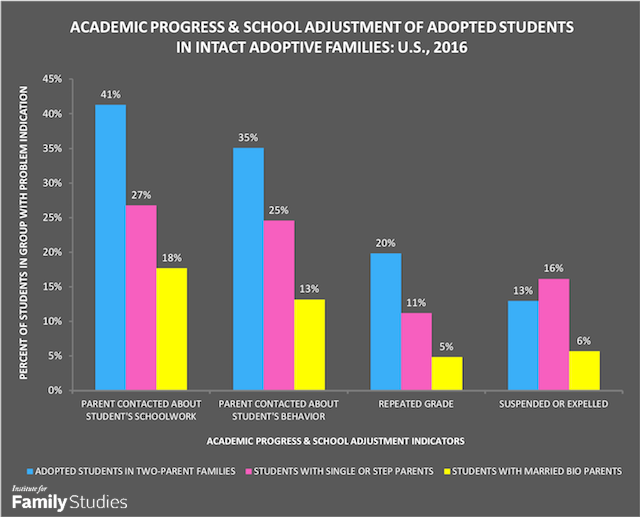

Figure 1 below shows how adoptive students in intact, married families compared with biological children in intact, married families on indicators of academic progress and adjustment.1 It also shows how these adoptive students compared with those in single birth parent and birth parent-stepparent families.

On each of the indicators, the adoptive students had significantly higher levels of performance and behavior problems than biological children in intact, married families. They did not always have higher levels of problems than the single- and step-parent group, however. In particular, the adopted students were not significantly different than the single-step group with respect to suspension or expulsion frequencies (13% versus 16%). Adoptees in two-parent families were less likely to be suspended than those living with single adoptive parents (13% versus 27%), although the significance of the difference was marginal.

2. Are the patterns similar for children who were born in a foreign country versus children born in the United States? Do you have any information about the age when they were adopted and the relationship between the age a child was adopted and these outcomes?

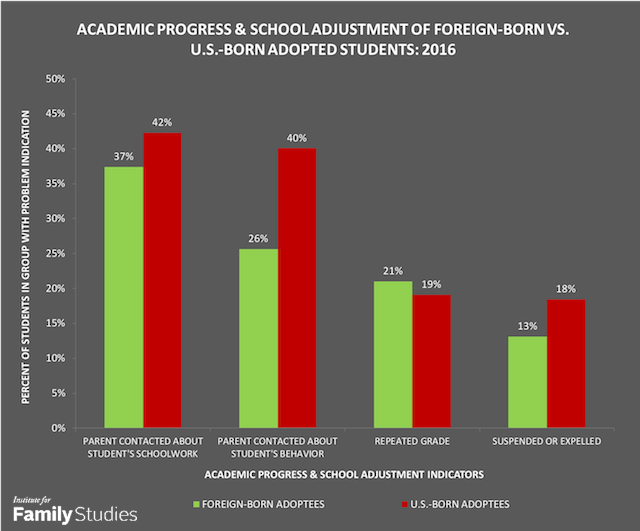

Figure 2 below shows how adoptive students born in foreign countries compared with adopted students born in the U.S. on the same academic progress and school adjustment indicators mentioned above.2 The foreign-born adoptees were less likely than U.S.-born adoptees to have their parents contacted due to classroom behavior problems (26% versus 40%), although the significance level of the difference was only marginal. The foreign-born students appeared to have a lower frequency of suspension or expulsion (13% versus 18%), but this difference was not statistically significant. The rates of parent contact for behavior and suspension for foreign-born adoptees were not significantly higher than those for non-adopted students, however.

On the other hand, the foreign-born adoptees did have significantly higher rates of parent contact due to schoolwork problems and of grade repetition than non-adopted students. And their learning-problem rates were not significantly different than those for U.S.-born adoptees, as may be seen in the figure.

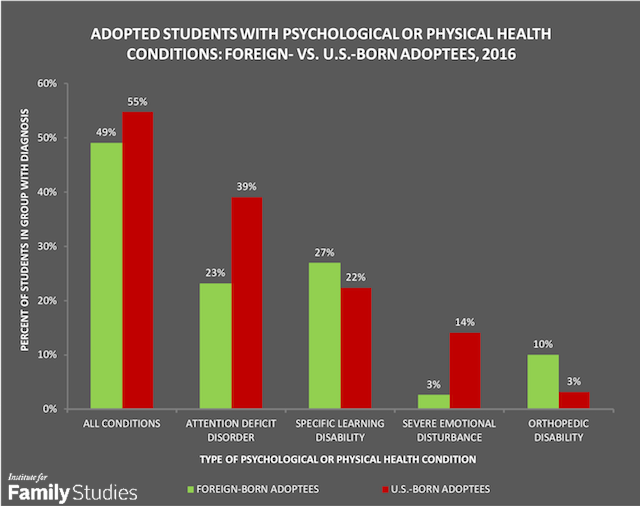

Figure 3 below shows how foreign-born and U.S.-born adoptees compared on the frequency of psychological and physical health conditions. The total percentage of students with one or more of the health conditions did not differ significantly (49% for foreign-born, 55% for U.S-born). Both percentages were significantly higher than that of non-adopted students. Foreign-born adoptees were less likely than those born in the U.S. to be diagnosed with attention-deficit disorder and severe emotional disturbance. In addition, foreign-born adoptees were not significantly different than non-adopted students with respect to severe emotional disturbance.

Foreign-born adoptees were as likely as U.S.-born adoptees to be diagnosed with a specific learning disability. They were significantly more likely to have an orthopedic disability. Previous research on foreign adoptions has found that the likelihood of the child having a severe health condition varies across different countries of origin.3 A frequent problem with foreign adoptions is the limited and sometimes questionable information available to potential adoptive parents about the social and health background of the birth parents and the health history of the child.

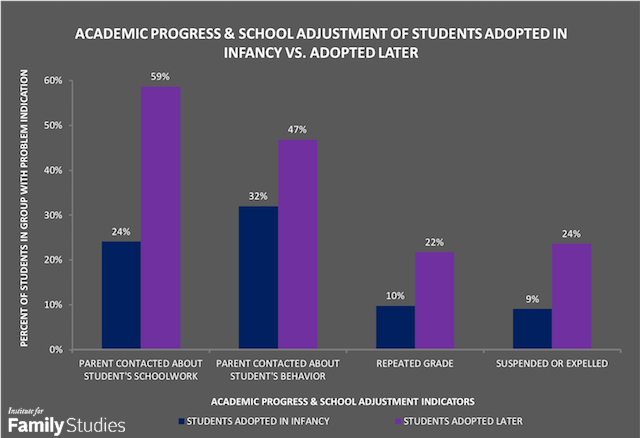

Information about the age at which students were adopted was only available for a subset of the adopted students in our survey sample.4 Based on this subset, we found that students adopted in infancy (i.e., at or under age 1) had less than half the rate of suspension and parent contact due to schoolwork problems as students adopted at later ages. Both differences were statistically significant. Also, the adopted in infancy group had half the rate of grade repetition, but this difference was only marginally significant. An apparent difference in parent contact due to child behavior problems (32% versus 47%) was not statistically significant. Despite their lower problem rates, students adopted in infancy still had higher rates than those living with married birth parents on several problem indicators.

These findings, though necessarily tentative, are consistent with those of previous studies and with child development principles.5 There is clearly a need for further and more definitive research on how the circumstances of adoption, especially the age at adoption and adoption from foster care, affect the likelihood of academic and behavioral difficulties for the child.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce. W. Bradford Wilcox is a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies and the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia.

1.Note: 288 students or 67% of adopted students were living with two married-parent families (weighted percentage). The intact-adopted families include same-sex married couples.

2. Note: 79 or 17% of the adopted students in the NHES sample were foreign-born. The statistical power of comparisons involving this subgroup is limited by the relatively small subsample size.

3 Gunnar, M.R., Van Dulmen, M.H.M., & The International Adoption Project Team. (2007). Behavior problems in post-institutionalized internationally adopted children. Development and Psychopathology. Vol. 19, 129–148.

4. A question about the age at which students were adopted was not explicitly asked in the NHES questionnaire. We have been able to surmise the likely age based on questions about the age at which the adult respondent first became a parent and, for foreign-born children, the age at which the child entered the U.S. The subsample with such information consists of 237 students, or 51% of the adopted students.

5. Vandivere, S., Malm, K., & Radel, L. (2009). Adoption USA: A chart book based on the 2007 national survey of adoptive parents. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.