Highlights

Richard V. Reeves argues in his provocatively titled book that upper-middle-class Americans have become Dream Hoarders. In our determination to see our children succeed, he writes, we resort to unfair tactics and end up depriving other people’s children of the chance to attain the American dream.

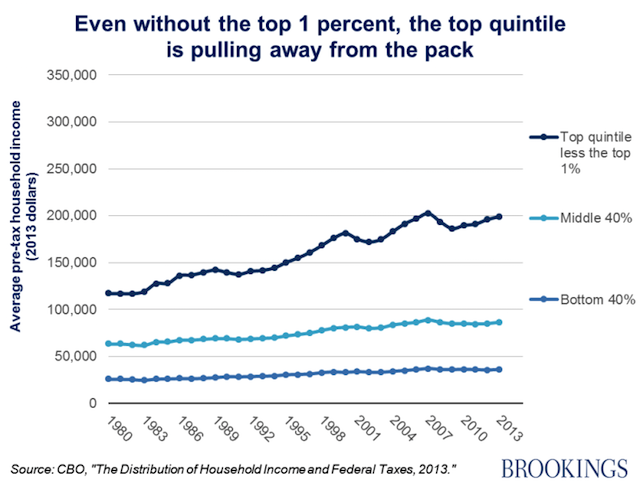

Unsurprisingly, this accusation has some of his readers up in arms. Looking at the thorny problems of inequality and social (im)mobility, we all want to blame those richer than we are—and raise their taxes to address the situation. Reeves does not dispute that the disproportionate economic gains of the top 1% of income earners are unjust. Yet CEOs and celebrities are not the only ones who have benefited from the economic and political changes of the past four decades—so have the other Americans in the top income quintile: the households earning over $112,000 a year, more than 80% of American families. The figure below, which excludes the top 1% of earners, illustrates just how much the income of upper-middle-class households has risen since 1980.

In terms of education, marital stability, health, and longevity, too, this group is doing better than the other four income quintiles. The children of these Americans are far more likely than their peers to graduate from college, attain great jobs, and earn top-quintile incomes themselves—thanks in no small part to their parents’ advantages.

This is where the thorny questions arise. In addition to genetic engineering, or handicapping the genetically blessed, giving all kids a truly equal shot at achieving the American dream would require incredible invasions of freedom. Beyond maintaining the exact same standard of living for all families, the government would need to make parents’ decisions for them, from who takes care of infants, to which schools children attend, to how high-schoolers spend their free time.

Most parents do their best to help their children succeed in school and beyond, but today’s upper-middle-class parents have taken that mission to a new level. In New York City, some parents pay tutors to prepare their four-year-olds for a test that determines admission to the city’s “gifted and talented” public elementary schools. What can any of us do to stop them? Or how can we ensure that disadvantaged kids receive anywhere near the same amount of attention and resources in the course of their education?

Reeves recognizes that the barriers to economic mobility in a free society are formidable. Instead of calling for upper-middle-class parents to curtail their frantic efforts, as some of them probably should, he distinguishes between fair methods and unfair methods of promoting your children’s success. Moving into a neighborhood with good schools is fair; using exclusionary zoning to keep poorer families out of the area is not. Helping your son study for the SAT and apply to college is fair; legacy preferences in college admissions are not. Covering your daughter’s living expenses during her unpaid summer internship is fair; securing that internship for her by calling up your friend is not.

As one would expect from a Brookings Institution senior fellow, Reeves also puts forward a number of public policy reforms to restore the American dream. Several aim to directly address the kinds of “opportunity hoarding” outlined above. Other ideas include expanding home visiting programs to provide more disadvantaged couples with advice on parenting and child health, offering higher salaries to great teachers willing to work in the poorer schools, and dedicating more federal resources to community colleges. He would fund such programs by raising income taxes, particularly by ending the tax breaks that favor the upper middle class.

While I’m sympathetic to Reeves’ concerns, and to many of his specific proposals for legislators and individual Americans, I finished the book feeling if anything more pessimistic about the problem he describes. If intergenerational mobility in the U.S. has been stable during decades that saw major social and economic changes, as some respected research cited in the book suggests, how much would his ideas really move the dial?

Reeves noted in a weekly newsletter earlier this year that some of his readers and friends want to become better dream hoarders, a fact that underlines what a tough battle he seeks to wage. Few Americans share his visceral passion for fair play when their own kids’ future is concerned. In a society as materialistic as ours, Reeves may need to call on stronger forces than a sense of fairness. It does not seem likely that people whose vision of the good life is primarily material—defined mainly by income, social status, and lifestyle—will voluntarily risk their children’s chances of reaching the top echelons of American society. Our willingness to expend more of our energy and resources on other people’s children could depend on redefining success for our own. Without abandoning political activism entirely, perhaps we should turn some of our attention away from parenting experts and political pundits, and listen more to philosophers and people of faith.

Anna Sutherland is a writer and editor living in Michigan.

Editor's Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.