Highlights

- How can we expect parents to be both breadwinners and caregivers unless we adjust policy in a way that better fits these new realities? Post This

- A top priority should be to ensure all experienced workers access to 12 weeks of paid time off for the birth or adoption of a child and for their own illness. Post This

- Rebalancing caregiving between men and women should be one objective of any new policy. Post This

Editor's Note: In the final essay in our family policy symposium, Isabel Sawhill, senior fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, details her vision for an uncomplicated paid family leave plan.

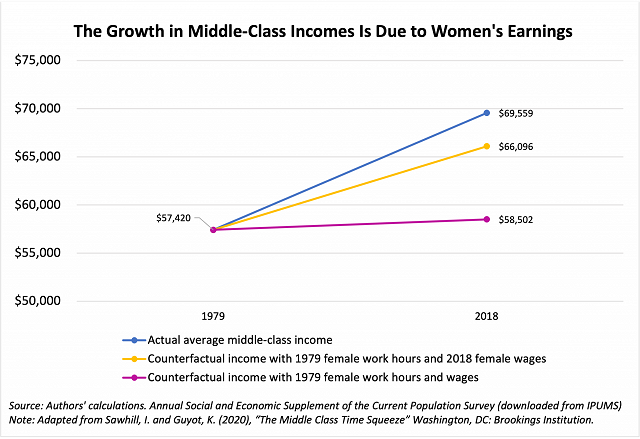

More and more women have joined the work force over the past half century with the result that most women are now employed. Before the pandemic, women held half of all payroll jobs, and 40% of all mothers were the only or primary breadwinners for their families. An analysis of what would have happened to middle-class incomes if women had not joined the work force shows that virtually all of the increase in such incomes between 1979 and 2018 resulted from women’s increased employment. Without women’s economic contributions, middle-class incomes would have stagnated for 40 years.

This development has created a new problem: “a time squeeze.” How can we expect parents to be both breadwinners and caregivers unless we adjust policy in a way that better fits these new realities? Families need more child care, school hours better aligned with work hours, flexible and predictable hours on the job, and more paid leave. Here, I focus on paid leave but would emphasize that all of these policies need to be part of a package for working families. With flexible hours and more telecommuting, for example, it would be far easier for parents to combine work and child rearing.

Discussions of paid family leave have tended to focus on three types of leave: parental leave taken when a new baby is born or adopted, medical leave taken for one’s own illness, and caregiving leave taken to deal with the illness of a child, a spouse, or an elderly parent.

There is more consensus around the need for paid parental leave than there is around the need for medical or caregiving leave. My own view is that a top priority should be to ensure all experienced workers access to 12 weeks of paid time off for the birth or adoption of a child and for their own illness. The policy might cover 80% of earnings up to a cap of, say, $1,000 a week. Some thought should be given to limiting such paid leave to those with incomes below $75,000 a year in order to target the benefits to those who need the most help. An earnings-replacement rate of less than 100% would create an incentive for workers to return to work. The program could be financed by a modest addition to payroll taxes on both employees and employers. The specific parameters of the policy and its costs should be open to debate. As for medical leave, ideally, any new benefit should be integrated with existing policies on sick leave and long-term disability insurance under Social Security (SSDI). But while we are waiting for such a restructuring to occur, all workers should be ensured against income loss as the result of a serious illness.

The birth or adoption of a child is an infrequent and easily defined event, and both research and professional opinion suggest that there can be benefits for both children and their parents if time is set aside for bonding with a new baby. Parental leave should be provided to both mothers and fathers with a “use it or lose it” component for fathers. When fathers take paid leave, it has been associated with an increase in their parenting involvement, leading to more engagement in their children’s lives over the longer term. Rebalancing caregiving between men and women should be one objective of any new policy. Without an evolution in gender roles, the burdens will continue to fall disproportionately on women, and any new family policy designed to address this gender-specific burden could simply lead to employer discrimination against the hiring or promotion of women.

Caregiving leave, in contrast to parental leave, is less well-defined. Who should be eligible to take it (a parent, a spouse, an adult child)? Under what conditions should it be authorized (the illness of a child, disability of a spouse, medical appointments or chores done for an aging parent)? The list of possible conditions and the duration and continuity of any time commitment needed for “the caregiving” is almost endless, raising difficult questions for those either formulating or administering the policy.

These complexities lead me to argue for a policy that simply provides a certain amount of paid leave to all workers, including leave for caregiving, but without trying to specify the purpose for which it is taken in law. It should rely, instead, on a combination of a time limit on that paid leave, and evolving social norms and practices around when such leave-taking is deemed appropriate.

America is a diverse country, fewer and fewer people are embracing parenthood, most people will not face a major medical event during their working years, and workers face many personal emergencies and should have the flexibility to take time off for a variety of reasons of which family caregiving is only one. People need time off from work to attend their children’s school events, meet with teachers, serve on a jury, do volunteer work in their community, attend a funeral, make home or car repairs, help a neighbor, take a class at a community college, or simply to vacation or catch up on personal chores and sleep. For these reasons, many large companies now offer a certain fixed amount of paid time off and allow their employees the flexibility to choose how they will use it. The problem is that not all companies do this, and it tends to be smaller businesses and lower-wage workers that lack such leave.

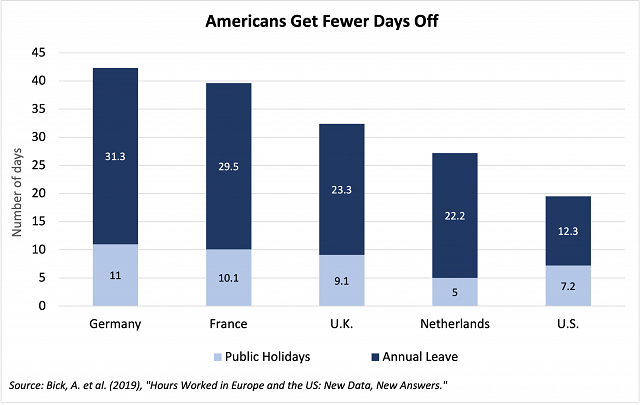

For these reasons, in addition to 12 weeks of paid leave for parents specifically, I also favor a national policy under which every worker would be guaranteed access to 20 days of paid leave every year for any reason (prorated for part-time workers). As shown in the figure below, European countries provide far more time off than does the U.S., and the adoption of 20 days of paid leave per year would still leave the U.S. behind other wealthy nations.

The advantages of such a policy over a more categorical approach, where government specifies all of the parameters under which paid leave may be taken, include administrative simplicity, flexibility for workers, and ease of understanding and of use. States that currently offer paid leave for caregiving have experienced low take-up rates, probably because of lack of knowledge or the administrative burden put on applicants. Those of us who write about, or make public policy, love to design complicated schemes. Their lack of popularity among the general public is contributing to an understandable lack of confidence in, or respect for, their government.

In sum, let’s offer workers more time off with pay but keep it simple—with a longer period only in a few special cases, such as one’s own serious illness or a new baby joining the family.

Isabel V. Sawhill is a senior fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, working in the Center on Children and Families and on the Future of the Middle Class Initiative.