Highlights

- A large minority of young men who are not working, or who are working less than full-time, are collecting food or cash from the government. Post This

- In 2024, 3.8 million men ages 25 to 40 were not in the labor force, and a total of 7.8 million were not working full-time. Post This

- Work done by Princeton's Mark Aguiar and colleagues indicates that screentime—from gaming to porn—can account for nearly half of the drop in working hours for men in their 20s from 2004 to 2017. Post This

American men are in trouble. From Richard Reeves’ Of Boys and Men to Nicholas Eberstadt’s Men Without Work, we have learned that men are opting out of our most important institutions—work, education and family—in record numbers. But what or who is to blame for this male malaise?

Uncle Sam.

This was Allysia Finley’s thesis, writing about men’s growing disconnect from work in a recent Wall Street Journal article: “Blame government, which showers benefits on able-bodied people who don’t work,” Finley wrote.

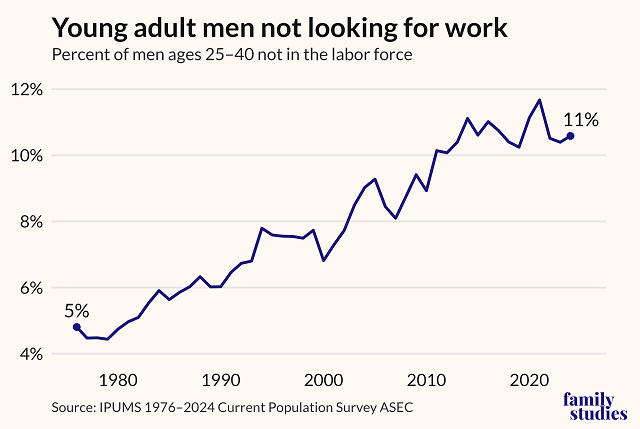

Finley is certainly right that we have a growing problem when it comes to young men’s connection to work. In 1976, just 5% of young men ages 25 to 40 were not in the labor force. That number has more than doubled, rising to 11% in 2024. Over the same period, the share of men in this age range not working full-time rose by 46%, such that now more than 1 in 5 men in this age group are not working full-time. In 2024, 3.8 million men ages 25 to 40 were not in the labor force, and a total of 7.8 million were not working full-time.

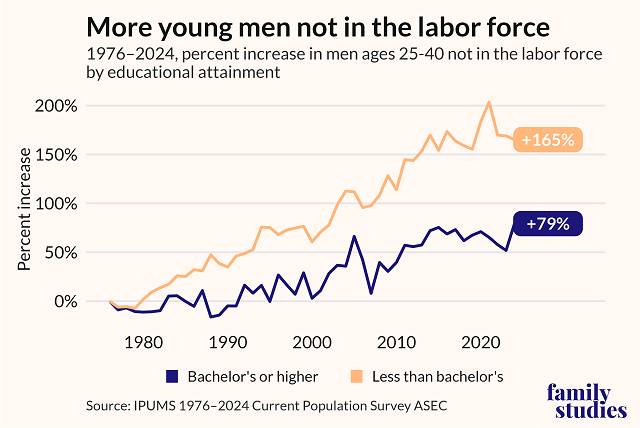

What’s also apparent from these trends is that working-class men have been much more affected by the male flight from work than college educated men. The increase is only up 79% among college educated men, whereas it is up 165% among less-educated men. This is worrisome because such men are more likely to end up poor, unmarried, depressed, and prone to succumbing to “deaths of despair.”

But is Finley right to blame the government for this male flight from work? Yes, in part, it would seem. A large minority of young men who are not working, or who are working less than full-time, are collecting food or cash from the government.

The 2024 Current Population Survey indicates that 31% of men ages 25-40 who are not working full-time collected some form of cash or cash-equivalent benefit in the form of food stamps, Social Security for disability, Supplemental Security Income, or unemployment insurance in the prior year. Such benefits are particularly common among the nearly 4 million men in this age group who are not in the labor force, of whom 40% had received some cash or cash-equivalent government benefit. This doesn’t include other non-cash government supports, like health insurance or reduced rent.

We should note that national surveys, such as the Current Population Survey, tend to underreport the share of adults on such programs. To Finley’s point, the share of young men receiving one or more of these benefits is likely higher than what the CPS indicates. But these benefits are largely going to those without college degrees. Furthermore, there is a large share of those who did not receive any such benefits and so are clearly not being enticed by Big Government. There is more to this story.

So, what besides Uncle Sam is to blame? Our work at the Institute for Family Studies suggests broken families and big business also have a big hand in this male malaise. Regarding family, as Brad Wilcox wrote in his book Get Married, young men are “more likely to end up idle, to work less, and to earn less money if they came from a non-intact family.” He added, “In fact, these young men are 36% less likely to hold down a full-time job by the time they hit their mid-twenties.”

When it comes to big business, as Wilcox noted in The American Conservative: “Many of the nation’s biggest businesses — from Alphabet (YouTube) to TikTok to Microsoft (Xbox)—are selling products that serve teenage boys and young men one dopamine hit after another. The problem with these products is they make school and work relatively less appealing, inhibiting the ability of many young men to develop the skills, ambition, and work ethic that would enable them to thrive in the twenty-first century economy.”

Work done by Princeton economist Mark Aguiar and his colleagues indicates that screentime—from gaming to porn—can account for nearly half of the drop in working hours for men in their twenties from 2004 to 2017. Of course, many parents of teenagers understand this problem starts before men hit their twenties.

Throw in the well-documented failures of schools to cultivate the hearts, minds and talents of boys and young men, and what Eberstadt calls a “normative sea change” that has made it a “viable option” for “sturdy men ... to sit on the economic sidelines, living off the toil or bounty of others” and you get a fuller picture of the familial, economic and cultural forces arrayed against our young men.

The bottom line is that, yes, government handouts can, and do, sustain the growing male disconnect from work. But the story of young men and unemployment is about much more than the failures of Uncle Sam. There is plenty of blame to go around.

Grant Bailey is a research associate at the Institute for Family Studies. Brad Wilcox is Distinguished University Professor and Director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and senior nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Editor's Note: This article appeared first at Deseret News. It has been reprinted here with permission.