Highlights

If your doctor reports that she’s doing the best she can, what are you thinking? How about if your plumber tells you the same thing? Even my pilot’s best efforts to land the plane after an engine failure that was clearly not his fault don’t inspire me to expect a good landing. In short, “doing the best I can” implies that something desirable is lacking, regardless of where the fault lies.

This is certainly the case for the inner-city single fathers in Kathryn Edin and Timothy J. Nelson’s recently released book Doing the Best I Can. And while the authors (as good sociologists) locate these men’s poverty in a history of deindustrialization, suburbanization, and the like, they do not shy away from highlighting the men’s personal failures and rationalizations. The men’s nuanced biographies intersect with history, geography, culture, and public policy.

The caricature that the authors were explicitly investigating—and that they succeeded in destroying—is that of the hit-and-run father who doesn’t care about his kids. But I think their attack on that caricature was more than that. Ever since the 1965 Moynihan report was blatantly mischaracterized as blaming black poverty on the lack of family-supporting values in black culture, it has been dangerous for academics and policy wonks to take a hard look at values in the inner city. Imagine if the subjects really had attitudes that the mainstream culture found repugnant: As Moynihan was among the first to discover, no matter how vociferously you blamed white America for attitudes and institutions that disempowered black men and weakened family ties, you would still be accused of blaming the victim.

Fast forward to 2013. It isn’t all about race anymore because Americans of almost every color are having children outside of marriage at higher rates than blacks were in 1965—yet it is still risky to take an in-depth look at the values of inner-city fathers who are failing in multiple ways. Edin and Nelson said they wanted to find out if these fathers cared; I think they wanted to find out whether their parenting values were really all that deviant.

It is the clash between single fathers’ mainstream values and their circumstances that creates some of their problems.

Edin and Nelson will not get skewered like Moynihan did, in part because they found in the inner city many values indistinguishable from those in middle-class America. The men they interviewed share common ideals of what marriage should be, namely a union with a soul-mate that is entered into late enough in life that both maturity and financial stability have been achieved first. Further, these men have adopted the “new father” ideology that emphasizes relational aspects of fatherhood: they want to be involved in their children’s lives in multiple ways.

In fact, it is the clash between single fathers’ mainstream values and their circumstances that creates some of their problems. What’s a guy to do when he wants to marry a soul-mate after he has a stable job, but he’s never stayed fully employed longer than four months? How does he re-establish a relationship with a child after an incarceration? How does he overcome humiliation if the mother’s boyfriend can treat his own child to ice cream, but he cannot? How could he keep his child overnight when he’s living in a halfway house or sleeping at a job site?

Edin and Nelson write almost poetically as they help us understand the allure of fatherhood when contrasted with almost everything else in these men’s lives. Having children is a positive achievement, provides relationships with no negative history, and makes a difference for the future—all of which benefits are difficult to come by in neighborhoods where violence, crime, addiction, abuse, and poverty are commonplace. Their chronicle of the violence in one father’s neighborhood the year his child was conceived draws you into the tragedy—by the time they reach the end, the concluding plea of an elementary student’s award-winning essay to “put down the guns and pick up the babies” is exactly what you want everybody to do. And while it might be surprising that pregnancies that were neither planned nor the result of serious relationships are happily welcomed, it nonetheless makes sense. Put differently, children are a great counter to an emasculating society.

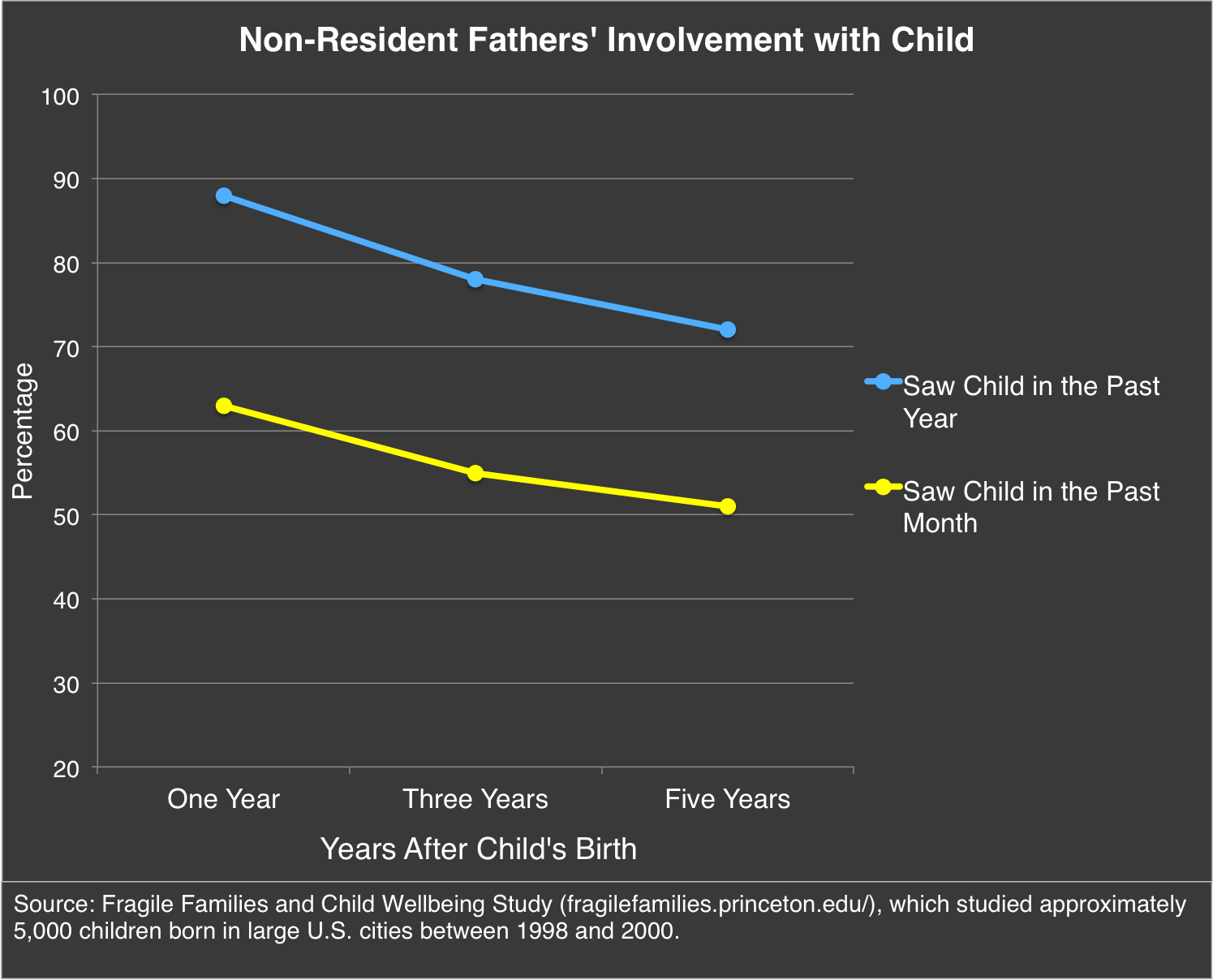

But needless to say, welcoming a child and wanting to be involved in its life do not guarantee parenting success. A large majority of the men who have a child outside of marriage are no longer in a relationship with the child’s mother by the child’s fifth birthday. Even just “being there” for their children gets harder without coresidence, as the below chart shows, especially if the mother has a new partner. Many fathers consider it an achievement when they are able to provide for themselves and give their children whatever is left over, even when it falls far short of what the mother contributes or what the child needs. When their own new partners result in new children, fathering efforts are often focused only on the new children.

Edin and Nelson’s concluding recommendation calls for a realignment of America’s social institutions to value men’s parenting—to grant men rights along with their responsibilities. The authors admit that specific ways this might be achieved are unknown, but offer two compelling reasons that valuing low-income single men’s parenting could help break the vicious cycle. First, men who are able to stay involved with their children might not be compelled to “start over” with new children. Second, the men in their study who stayed involved with their children were more likely to stay out of prison, stay sober, and work consistently. Most started with good intentions, but those who stayed involved with their children were more likely to succeed.

Edin and Nelson are right that there are few sources of meaning, identity, esteem, and even redemption in the lives of inner city men other than children. If these were derived from churches, jobs, or marriage, the allure of children would still be strong, yet the discipline necessary to defer fatherhood would be more attainable. But this is my reading: we will do well to listen to the authors themselves who recommend intervening later in the game by helping men stay attached to their children. Earlier intervention may be better in theory, but there are plenty of children who need their fathers and fathers who want to be involved with their children today. And further, Edin and Nelson might be right that nurturing these attachments might help break a perpetuating cycle.

So we need to get serious about figuring out what the specific programs might look like. Fathers and children cooking together instead of just being served at soup kitchens might be a start, or perhaps growing food together in church-sponsored gardens—something that might help combat the dearth of fresh produce in the inner city, too. Venues that mothers trust and where fathers can contribute with their children seem essential to restoring fatherhood in the inner city.