Highlights

- Men with low incomes, particularly the unemployed, are less likely to be married, and if married, they are more likely to be divorced. Post This

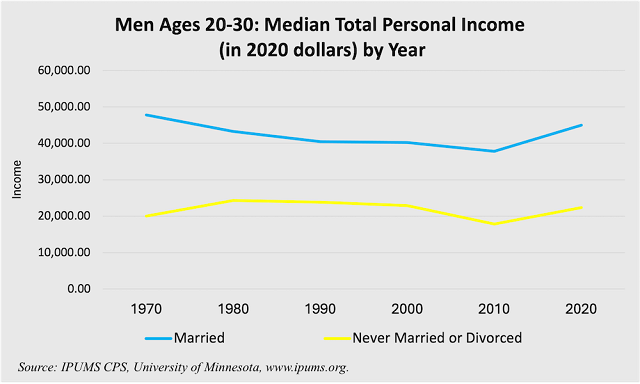

- Young men who women choose to marry and stay married to still earn a lot more (about twice as much) than never-married or divorced men, and this has changed very little since 1970. Post This

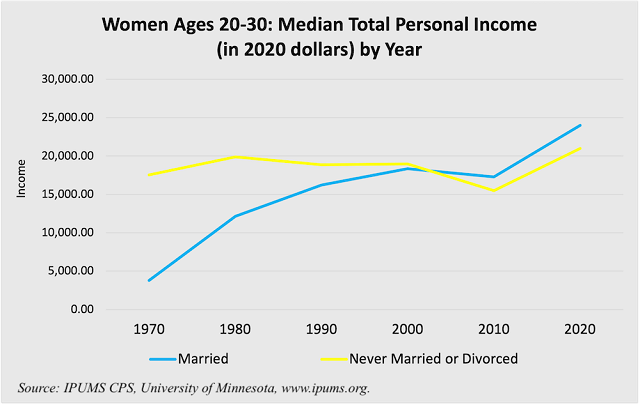

- Among young women ages 20 to 30, married women now make more money than never-married or divorced women, a reversal from 1970. Post This

“I will do anything, Nerissa, ere I will be married to a sponge,” the heiress Portia tells her personal assistant in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Portia is speaking about her desire to avoid marrying one of her suitors, who is a drunkard. The word “sponge” here means “one who soaks up alcohol” but it also implies “one who soaks up money or other advantages,” that is, the mooch kind of sponge. As usual, Shakespeare highlights a key and consistent aspect of human nature: Portia does not want to marry a man who sponges off her.

Despite 21st century America being a very different place than Shakespearean England, women’s mate preferences have not changed as much as we might like to think. In the last 50 years, there have been huge shifts in American society, as women’s participation in the labor force has increased and female earnings have surged, while men’s participation in the labor force has fallen and male earnings have stagnated. Yet women still prefer a husband who can credibly support, or assist in supporting, a family. Men with low incomes, particularly the unemployed, are less likely to be married, and if married, they are more likely to be divorced.

This can be further illustrated with census data on the median income for men in the prime marriage ages of 20 to 30 from 1970 to 2020. Despite the major changes in women’s employment and earnings over this time, the young men who women choose to marry and stay married to still earn a lot more (about twice as much) than never-married or divorced men, and this has changed very little since 1970. From a purely economic standpoint, this makes no sense. The increase in women’s wages relative to men’s would suggest that a man’s income would become less of a factor in marriage decisions as women earn more. Yet this is not the case.

The persistence of the breadwinner norm can be explained by theory and research from evolutionary psychology, which has provided abundant evidence that in all cultures, breadwinning ability is a more important characteristic in a potential spouse for women than it is for men. At root of this is the fact that a woman’s fixed biological investment in each child is greater than a man’s. For men, income earning capability in a potential spouse is less important than other characteristics, such as age. This doesn’t mean that other characteristics, such as education and earning ability, are not important in a potential wife. The societal cultural context also plays a role. It is now easier and acceptable, even expected, for women to work post-marriage and even when she has children. As a result, among young women aged 20 to 30, married women now make more money than never-married or divorced women, a reversal from the situation in 1970 (see Figure 2). Together, Figure 1 and Figure 2 show that marriage among 20- to 30-year-olds is now concentrated among both higher-earning men and higher-earning women.

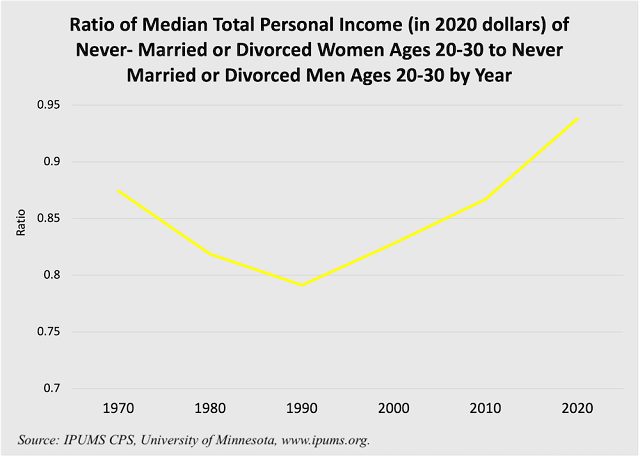

Further, Figure 3 shows that the ratio of the income of unmarried women ages 20 to 30 to the income of unmarried men ages 20 to 30 is higher than it is has ever been. Yet this poses a problem for marriage. If unmarried women prefer partners who have similar or higher incomes than themselves, this means that there are fewer marriageable, unmarried young men today than 50 years ago. It is perhaps not surprising that the age at first marriage is higher than it has ever been, and the proportion of the population never marrying by age 40 is at a record high.

Because education is linked to how much a person can earn, it is also not surprising that the people most likely never to get married are those with a high school education or less, particularly men. Unfortunately, the trend in lower proportions of men both attending college and graduating from college means that the decline in marriage rates is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. There is no getting around the fact that most women, like Portia in the story above, do not want to marry sponges. It is up to the men in the U.S. to prove they are otherwise.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life (Routledge 2016), editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018), and author (with Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber) of Not So Weird After All: The Changing Relationship Between Status and Fertility (Routledge, 2024).