Highlights

Marriage is no “panacea for poverty,” according to a Center for American Progress (CAP) report by Shawn Fremstad released last week. “Marriage Won’t Cure Poverty,” read the Atlantic headline for an article by Rebecca Rosen spotlighting the CAP report. And, a few years ago, a prominent study by three sociologists framed the question in a way that sounds familiar: “Is Marriage a Panacea?”

When progressive policy makers, journalists, and scholars pose the question like this, the answer is never in doubt: marriage is no poverty panacea. Well, yes, of course. Any serious consideration of poverty must acknowledge the roots of poverty are varied; hence, marriage cannot be the singular answer to poverty.

But just because putting a ring on it won’t cure poverty, that doesn’t mean the converse is true: namely, marriage plays no role in the fight against poverty. In truth, marriage is one important tool, among others—from high-quality education to wage subsidies for low-income jobs—in the fight against poverty. It’s this qualified contribution that marriage can make in the fight against poverty that is largely overlooked in the CAP report and Rosen’s article.

Among today’s families and children, three sets of findings illustrate the power of marriage in the fight against poverty.

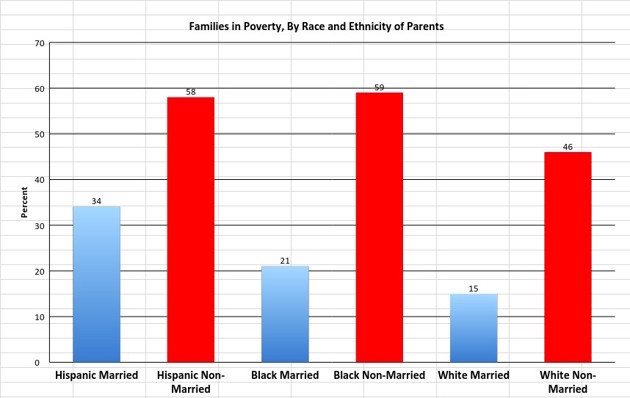

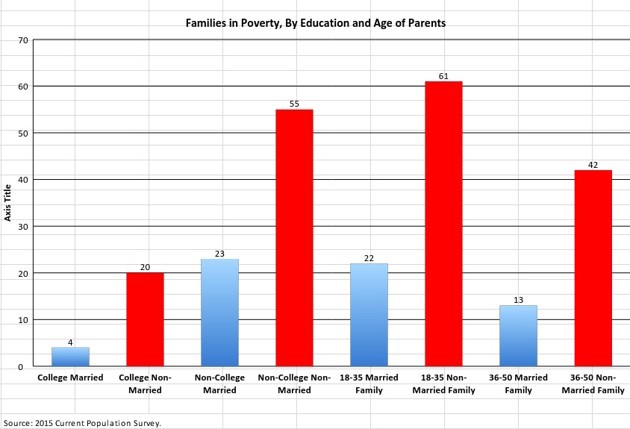

First, for individual families in a range of circumstances, marriage dramatically reduces the odds of poverty. As the two figures below indicate, whether you are college-educated or not, black, Hispanic or white, young or middle-aged, your family is markedly less likely to be poor if you are married (note: family poverty is indicated here by having a family income of less than 150 percent of the federal poverty line).

Specifically, being married is associated with a reduction in a family’s likelihood of poverty of between 41 and 80 percent, compared to a non-married family. Indeed, in a multivariate statistical model, data from the 2015 Current Population Survey indicate that marital status surpasses race, ethnicity, and age as a predictor of family poverty, and is about as important a factor as education. So, no panacea here, but marriage sure looks like a potentially important tool in any effort to fight poverty.

Second, child poverty is much lower in communities with lots of married families, even taking into account other factors—education, race, and local employment rates, for instance—that influence rates of child poverty. My research with the economists Robert Lerman and Joseph Price, for instance, indicates that states with higher shares of married parents have markedly lower rates of child poverty. Moreover, by our estimate, if states enjoyed 1980-levels of married parenthood, child poverty would be 17 percent lower and family median income would be 10 percent higher.

Third, the American Dream for poor children is strongest in communities and states with a higher share of married parents. Our research in a recent report, Strong Families, Prosperous States, indicates that children raised in families at the 25th income percentile enjoyed higher incomes at age 30 if they were raised in states with a greater share of married families. In fact, poor children from states in the top quintile of married families enjoyed 10.5 percent greater upward mobility as adults than poor children raised in states in the bottom quintile of married families, even controlling for factors like statewide trends in education, employment, and race.

For instance, even a comparatively less-educated state like Idaho—which ranks 40th in the share of its residents who are college-educated but 9th in mobility for poor children—was more likely to foster economic mobility for its poor children in part because it has stronger families (Idaho ranks 2nd in the United States in the share of its children in married families) than an equally less-educated state like Ohio, which ranks 43rd in mobility for poor children and 39th in the share of its residents who are college-educated, in part because it is also 38th in the share of its children living with married parents. In states and communities across the country, more married parents means that poor children have a better chance of breaking the cycle of poverty.

What’s more: as Lerman, Price, and I note in our report, the “family factor is generally a stronger predictor of economic mobility, child poverty, and median family income in the American states than are the educational, racial, and age compositions of the states.”

Now, Rosen acknowledges that poverty is less common among married families than among single-parent families. But she suggests the arrow of causality runs largely from affluence to marriage, with more money leading to more marriage for Americans, rather than vice versa. Rosen further says the marriage-less-poverty link “isn’t the result of the magic of marriage but the magic of addition,” given that many married families benefit nowadays financially from having two earners.

Rosen is certainly right to note that the arrow of causality runs, in part, from money to marriage. Today, Americans who are better educated and more affluent are more likely to get and stay married.

But the arrow of causality also runs in the opposite direction. Less-educated, minority, and younger families—who are all at a higher risk of poverty—face markedly lower levels of poverty if they are married, as the figures above show. That’s partly because they often enjoy the benefit of two earners, as Rosen acknowledges. But if they get and stay married, they also are less likely to incur the big costs associated with family breakups and multiple partner fertility, from lawyers’ fees to child support.

Finally, men without college degrees who marry work harder (about 400 hours more per year) and make more money (at least $17,000), in comparison to comparable peers who are single. Marriage seems to motivate men to work harder, more strategically, and more successfully, all of which boosts the average married family’s income.

So, there are a number of ways in which the institution of stable marriage works its “magic” in reducing the odds that families fall into poverty: It tends to boost the number of earners, minimize the costs of family instability, and motivate men to maximize their earning potential.

If you’re inclined to doubt or disagree with me, and you’re an Atlantic reader who is married with children, consider, seriously, what would happen to your family income, your home, your 40l(k), your annual vacation, and your children’s odds of attending the college or university of their choice if you got divorced in the next year? Many of you would lose a lot, and some of you would end up poor.

The math here is simple: two parents – one parent = one single parent. And, single parents, as we have seen, are much more likely to be poor than married parents. That’s math, not magic. And as Americans seek new and better policy solutions in the fight against poverty—from education reform to wage supplements for lower-income workers—we cannot lose sight of the fact that the math—more workers, higher-earning men, and less family drama—tends to favor parents who manage to get and stay married.

This piece first appeared at The Atlantic and is reprinted with permission.