Highlights

- One reason for the growing class gap in happiness is the growing marriage gap by class. Post This

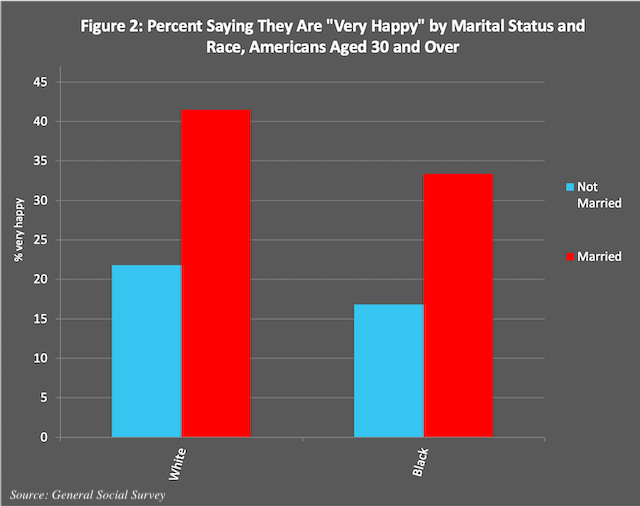

- In the GSS, 42% of married Whites said they were very happy, vs. 22% of unmarried Whites; 33% of married Blacks said they were very happy, vs. 17% of unmarried Blacks. Post This

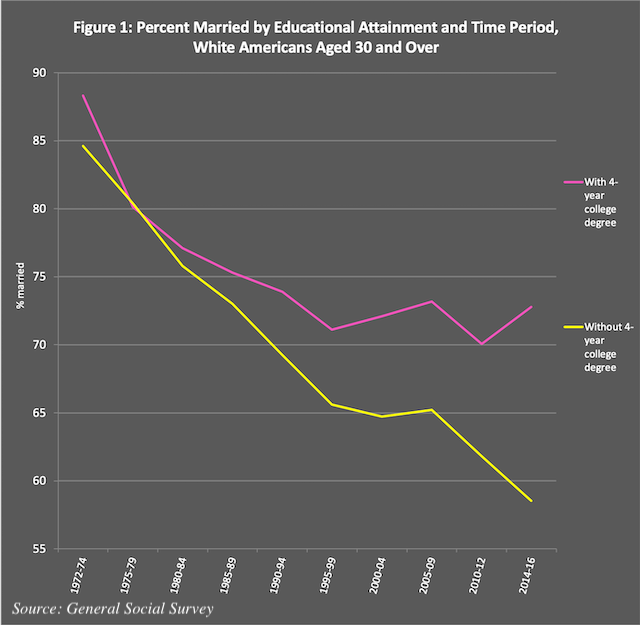

- Over time, the class gap in marriage rates has widened. Post This

What makes us happy? Many people would answer spending time with friends and family. But as it turns out, money can make a difference, too: There is happiness in not having to worry about paying your bills and in living in a comfortable and safe home.

In a recent analysis of 40,000 Americans over age 30 in the General Social Survey, we found that people with more money were happier, as were people with more education and more prestigious jobs.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Because the survey data went back to the 1970s, we were able to measure whether the link between happiness and money changed over time. It has: happiness is now more strongly linked to money than it once was. Happiness is also more strongly linked to education and job prestige, other measures of socioeconomic status (SES).

Among White Americans, the happiness of lower-SES people decreased over time as the happiness of higher-SES people stayed steady. Among Black Americans, the happiness of higher-SES people increased as the happiness of lower-SES people stayed the same. In both cases, the class gap in happiness widened between the 1970s and the 2010s. So not only does money seem to buy happiness, but it buys more than it used to.

The question is: Why? Income inequality is one reason: The divide between the rich and poor is much larger than it used to be. However, relationships also make a difference to happiness—more specifically, marriage.

Over time, the class gap in marriage rates has widened. While marriage rates (the percentage of people who are married) once differed very little between White Americans with a college education and those without, marriage rates have declined more among those without a college degree (see Figure 1; this zeroes in on Whites to rule out any possibility that effects are due to race).

This growing marriage gap matters for happiness because married people are happier than unmarried people by a fairly large margin. In the GSS, for example, 42% of married Whites said they were very happy, compared to 22% of unmarried Whites; 33% of married Blacks said they were very happy, compared to 17% of unmarried Blacks (see Figure 2; this uses all of the data from 1972-2016).

Over time, the number of unmarried people in the lower-SES group grew much faster than in the higher-SES group. The result: Less happiness among those with lower SES. Although marriage doesn’t account for the entire class gap, it does explain about half of it.

This data can’t answer the question of whether marriage causes happiness or happiness causes marriage. Nevertheless, it does suggest that one reason for the growing class gap in happiness is the growing marriage gap by class. If some of the causation goes from marriage to happiness, then encouraging marriage might be one way to close the gap.

Parents especially might consider talking to their teen children about marriage. In analyses of national surveys in my book, iGen, teens in the 2010s were less likely than teens in previous decades to say that marriage and family life were important in life. In interviews, many iGen teens said they associated marriage with boredom and a lack of freedom. Few seemed to associate marriage with happiness.

The growing class divide in happiness clearly has many causes, including income inequality. Still, relationships are also crucial for happiness, and for many people, marriage is their primary and most stable relationship.

No matter what its cause, the growing class divide in happiness is concerning. One study found that people who lived in countries with greater income inequality were less happy. The American dream of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” should be available to all, not restricted to the fortunate few.

Jean M. Twenge, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at San Diego State University and the author of iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy – and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood.