Highlights

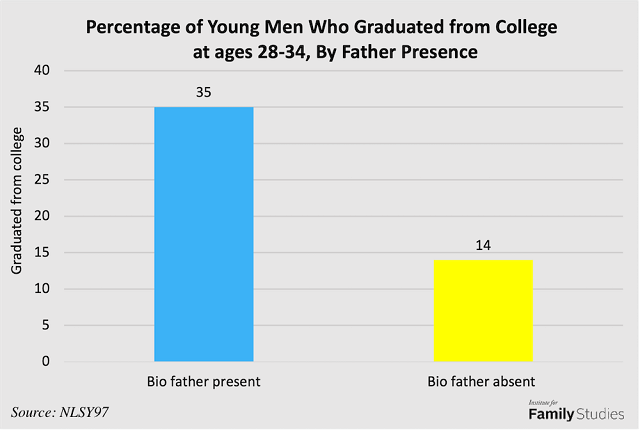

- Young men who grew up with their biological father are more than twice as likely to graduate college by their late-20s, compared to those raised without their biological father. Post This

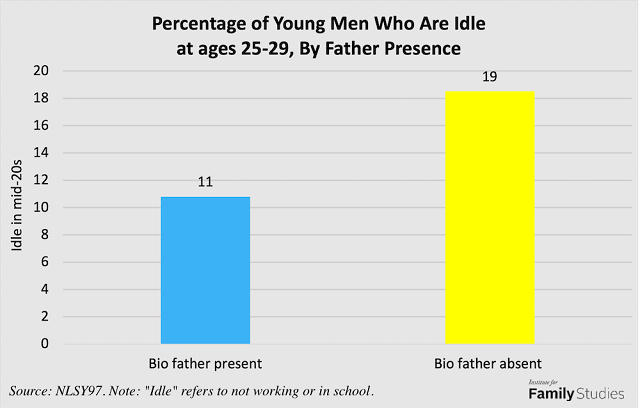

- Young men who did not grow up with their biological father are significantly more likely to be idle in their mid-20s. Post This

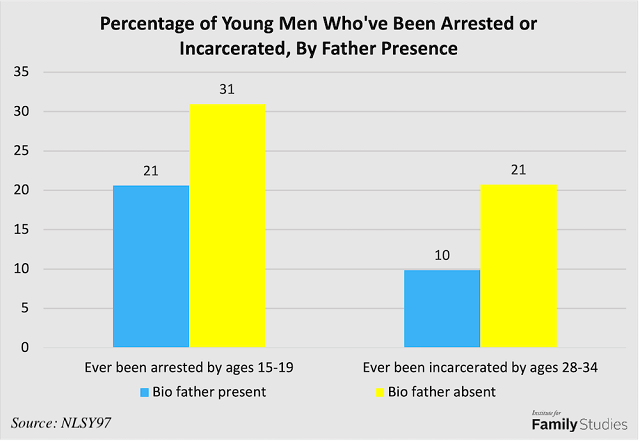

- Young men who did not grow up with their father in the home are about twice as likely to have spent time in jail by around age 30. Post This

“American fathers are today more removed from family life than ever before in our history,” wrote sociologist David Popenoe in his pathbreaking book, Life Without Father. “And according to a growing body of evidence, this massive erosion of fatherhood contributes mightily to many of the major social problems of our time.”

Popenoe wrote these words more than 25 years ago, but his assessment remains as relevant in 2022 as it was in 1996. The decline of marriage and the rise of fatherlessness in America remain at the center of some of the biggest problems facing the nation: crime and violence, school failure, deaths of despair, and children in poverty.

The predicament of the American male is of particular importance here. The percentage of boys living apart from their biological father has almost doubled since 1960—from about 17% to 32% today; now, an estimated 12 million boys are growing up in families without their biological father.1 Specifically, approximately 62.5% of boys under 18 are living in an intact-biological family, 1.7% are living in a step-family with their biological father and step- or adoptive mother, 4.2% are living with their single, biological father, and 31.5% are living in a home without their biological father.2

Lacking the day-to-day involvement, guidance, and positive example of their father in the home, and the financial advantages associated with having him in the household, these boys are more likely to act up, lash out, flounder in school, and fail at work as they move into adolescence and adulthood. Even though not all fathers play a positive role in their children’s lives, on average, boys benefit from having a present and involved father.

This Institute for Family Studies research brief details the connections between fatherlessness, family structure, and the increasing number of young men who are floundering in life and pose a threat to themselves and their communities. We do so by exploring the links between family structure and college completion, idleness (defined here as twenty-somethings not in school or working), and involvement with the criminal justice system (measured by arrests and incarceration) for young men in the 2000s and 2010s, using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 (NLSY97). We specifically examine how young men who were raised in a home with their biological father compare on these outcomes to their peers in families without their biological father.3 Here is what we found.

Father-Present Families Help Keep Their Sons on the College Track

Boys today are struggling at all levels of school, falling behind girls in reading and math skills, and are less likely than girls to graduate high school on time. Young men are also less likely than young women to attend or graduate from college. When we think about the many factors behind this gender gap, family structure is often not the first cause to come to mind. But as MIT economist David Autor has found, the gender gap in high school, including suspensions and graduation, is larger for boys who did not grow up in married families compared to boys who did.

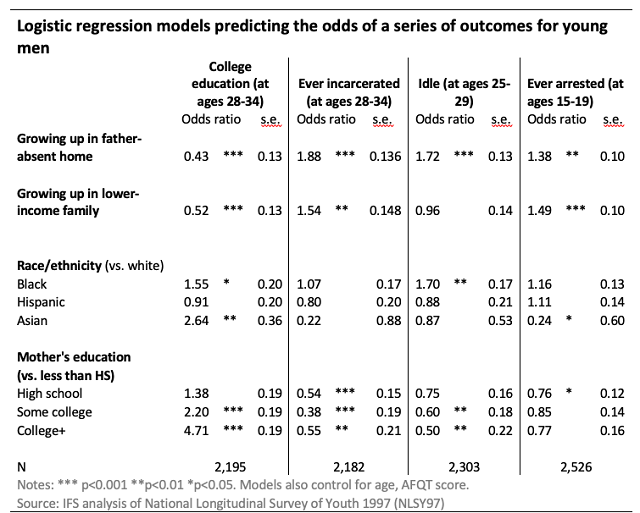

In this brief, we examine how the presence of a biological father in the home is linked to a young man’s chances of earning a college degree. As the figure below shows, when it comes to higher education for young men, family structure seems to matter. Young men who grew up with their biological father are more than twice as likely to graduate college by their late-20s, compared to those raised in families without their biological father (35% vs. 14%). Even after controlling for race, family income growing up, maternal education, age, and an AFQT score (a measure of general knowledge), we still see that hailing from a home with his own biological father doubles the likelihood that a young man will graduate from college.

Father-Present Families Discourage Idleness

A college degree is not the only measure of success. In fact, getting at least a high school degree and then a full-time job are two key steps toward avoiding poverty as adults. Unfortunately, more and more young men today are floundering without purpose and without work. As Nicholas Eberstadt and Evan Abramsky have reported, the U.S. has seen a surge in the number of prime-age men who are not currently working or looking for work: prior to the pandemic, nearly 7 million men between the ages of 25 and 54 were not working at all. The daily life of these men is often marked by hours in front of a screen while vaping, smoking marijuana, or under the influence of some other kind of substance.

So how does a father’s presence or absence effect his son’s ability or failure to launch—that is, to be either in school or in the labor force by the time he reaches early adulthood? Once again, we can see the apparent power of a biological father’s presence when it comes to pushing boys out of the house and toward becoming contributing members of society. As the above figure illustrates, young men who did not grow up with their biological father are significantly more likely to be idle in their mid-20s compared to young men who did grow up with their biological father (19% vs. 11%). After controlling for family income growing up, race, maternal education, age, and AFQT, we find that young men who did not grow up with their biological father are almost twice as likely to be idle compared to their male peers from father-present families (see Appendix table).

Father-Present Families Help Keep Their Sons Out of Jail

Of course, dads do more than just help their sons pursue an education and become productive members of society—they also play a major role in keeping their sons out of trouble. Research tells us that involved and present fathers reduce the odds that young men become a threat to society. Warren Farrell, author of The Boy Crisis, puts it this way: “Boys with dad-deprivation often experience a volcano of festering anger … And with boys’ much greater tendency to act out, the boys who hurt will be the ones most likely to hurt us.”

This figure illustrates his point. In addition to being markedly more likely to have been arrested during their teen years, young men who did not grow up with their father in the home are about twice as likely as those raised with their biological father in the household to have spent time in jail by around age 30. These associations remain strong and statistically significant even after controlling for family income, race, maternal education, age, and AFQT scores (see Appendix table).

Conclusion

In Wayward Sons: The Emerging Gender Gap in Labor Markets and Education, economists David Autor and Melanie Wasserman observed that “male children raised in female-headed households are less likely to have a positive male adult household member present,” are “particularly at risk for adverse outcomes across many domains, including high school dropout, criminality, and violence,” and, consequently, “the diminished involvement of the related male parent may magnify the emerging gender gap in educational attainment and labor market outcomes.”

Our results are consistent with their observations about the nexus between fatherlessness, family structure, and the problems the nation is now seeing among our young men. Too many young men are floundering and falling behind in one way or another—ignoring the imperative to get an education, failing to launch into adulthood, and succumbing to the lure of the street and becoming a threat to the community. This IFS brief reveals that America’s young man problem is disproportionately concentrated among the millions of males who grew up without the benefit of a present biological father. The bottom line: both these men and the nation are paying a heavy price for the breakdown of the family.

Brad Wilcox is director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, The Future of Freedom Fellow of the Institute for Family Studies, and Nonresident Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies. Alysse ElHage is editor of the Institute for Family Studies blog.

Appendix

About the Data & Methodology

The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 (NLSY97) follows the lives of a national representative sample of American youth (with black and Hispanic youth oversamples) born between 1980 to 1984. This cohort belongs to the Millennial generation (born between 1980 and 1994) and is the oldest group of Millennials. The survey started in 1997, when the respondents (about 9,000) were ages 12 to 16. The survey interviews were conducted annually from 1997 to 2011 and biennially since then. The analysis in this brief is limited to men, and the outcomes are measured in different life stages of this group of young men:

- Ever been arrested by ages 15-19: Respondents were arrested by the police or taken into custody for an illegal or delinquent offense (not including arrests for minor traffic violations).

- Idleness at ages 25-29: Respondents were not working nor in school.

- College education by ages 28-34: Respondents’ highest degree was a Bachelor’s or higher.

- Ever been incarcerated by ages 28-34: Respondents reported at least 1 incarceration.

1. Numbers are calculated based on the 2019 American Community Survey, and Lydia R. Anderson, Paul F. Hemez, and Rose M. Kreider, “Living Arrangements of Children: 2019,” Current Population Reports, P70-174, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2021.

2. Ibid.

3. In NLSY97, young men raised in a home with their biological father include those who lived with both biological parents (49%), or a biological father only (3%), or in a two-parent home with a biological father (2%) at the time of their first interview in 1997 (when these young men were ages 12-16). In contrast, young men in father-absent homes include those who lived with their biological mother only, or in a two-parent home with a biological mother and her partner, or with adoptive parents, foster parents, grandparents, etc.