Highlights

“Boys are on the wrong side of the education gender gap,” noted Christina Hoff Sommers in her groundbreaking book, The War Against Boys (2000), which sounded the alarm about the crisis facing boys in the classroom.

Unfortunately, not much has changed in the 16 years since Sommers’ book was originally published.1 Boys continue to lag behind girls and are less likely to graduate high school on time and to earn a college degree. Nationally, the gender gap for high school graduation rates is now about seven percent.

So, why are boys falling behind? Sommers has argued that part of the problem is an education system that typically caters to girls while overlooking the unique needs and learning style of boys. But a growing body of research demonstrates that the trouble boys are facing in the classroom may begin earlier—at home, with boys facing difficulties at home being particularly likely to flounder in school. This “family disadvantage,” as some researchers have described it, is more likely to occur in unmarried families, probably because boys seem to be hit harder by the absence of a father than girls when it comes to academic success.

An important study led by MIT economist David Autor found that the gender gap in high school graduation, school suspensions, and school absences is smaller in families with married parents than in unmarried families. As Autor explained to The New York Times: “Boys particularly seem to benefit more from being in a married household or committed household—with the time, attention and income that brings.” Another recent study conducted by psychologist William J. Doherty and colleagues revealed that the effects of the family disadvantage for boys extend into college, finding: “Males were disproportionately less likely than females to attend college if they came from a family in which the father had been absent from birth.”

A new report published today by the Institute for Family Studies (IFS) builds on this research to highlight the significance of family structure to the academic success of both boys and girls in Arizona. Co-authored by IFS Senior Fellow W. Bradford Wilcox and Nicholas Zill, Stronger Families, Better Schools finds that the presence of more married families in a school district is not only linked to higher graduation rates overall, but also to greater gender parity. This means that boys in Arizona are more likely to graduate, and to graduate at levels that parallel those of girls, in districts with more married families. In fact, the share of married families is a better predictor of high school graduation rates and gender equality in Arizona public school districts than are child poverty, race, and ethnicity in those districts.

These findings are particularly noteworthy because Arizona’s graduation rate of 72 percent is below the national average (82 percent), and unlike other states, it has not risen significantly in recent years. The Grand Canyon state also has a considerable gender gap, with boys less likely to graduate high school on time than girls. In 2014, for example, the graduation rate was almost 80 percent for girls, but less than 72 percent for boys in Arizona.

As the IFS report points out, one reason Arizona schools may trail the nation in high school graduation rates is that too many of its students are growing up in homes without married parents. The state ranks 33rd in the nation when it comes to its share of children in married families (67 percent). At the school district level, the share of children from married families ranges from as low as 25 percent to as high as 88 percent, with an average of 63 percent.

To measure the impact of family structure on student academic success in Arizona, Wilcox and Zill analyzed high school graduation rates from the state’s nearly 100 school districts according to several demographic characteristics of local districts: the proportion of married-couple families, the average educational attainment of adults, the child poverty rate, and the racial and ethnic composition of school-aged children.

High School Graduation Rates. Wilcox and Zill found that a district’s proportion of married-couple families and parental education were the two strongest predictors of high school graduation rates in Arizona. The share of married families in a district was stronger than child poverty, race, and ethnicity. After adjusting for education and race/ethnicity, there was a 3 percentage-point increase in graduation rates for every 10 percentage-point rise in married-couple families.

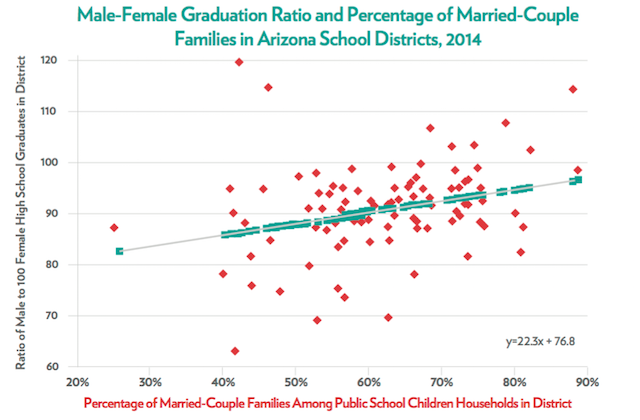

Gender Gap. The IFS study also found that boys are more likely to graduate at levels closer to girls in districts with more married families. Out of the 10 school districts in Arizona with the highest male/female graduation ratios, seven were above average in their share of married families, and four were in the top tenth of the distribution of married families. In contrast, among the 10 districts with the lowest male/female ratios, eight were below average in their proportion of married families.

As the figure above shows, after adjusting for socio-economic factors, there was a 2.2 point increase in the male/female graduation ratio for every 10 percentage-point increase in the proportion of married-couple families in a district.

These results show how family structure—particularly the presence or absence of married families in a school district—is linked to student success and gender parity. To improve high school graduation rates and help boys catch up with girls at school, the IFS report suggests that Arizona’s policymakers, civic leaders, and educators explore two initiatives aimed at strengthening marriage across the state:

- Expand and improve vocational education and apprenticeship programs in high schools and community colleges. While it may sound strange to suggest vocational programs as a way to strengthen families, voc-ed programs like Career Academies have been shown to increase the job and marriage prospects of young adults who are unlikely to earn a four-year college degree.

- Launch private and public campaigns to promote marriage organized around what Brookings Institution scholars Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill have called the “success sequence,” where young people are encouraged to pursue education, work, marriage, and parenthood—in that order. The success sequence should also be incorporated into family life education in public schools.

Stronger Families, Better Schools provides further evidence that what happens in the home may matter for children’s educational performance as much as what happens in school. By implementing policies and programs aimed at strengthening family life in the Grand Canyon State, Arizona can help boost the academic prospects of all students—especially its boys.

1. A new and revised edition of The War Against Boys was published in 2013.