Grant Martsolf, Brad Wilcox, Good Jobs, Strong Families. How the character of men's work is linked to their family status (The Institute for Family Studies, Penn’s Program for Research on Religion and Urban Civil Society (PRRUCS), 2025)

Media Coverage

John DiIulio, "The best natalist policy: good jobsThe makings of a second Baby Boom," UnHerd, May 26, 2025

Chris Bullivant, Grant Martsolf, Brad Wilcox, "Is the collapse of blue-collar marriage a foregone conclusion," The Washington Examiner, April 30, 2025

Grant Martsolf, "Good jobs, strong families in working-class America," Family Studies, April 29, 2025

Introduction

Over the last half century, the U.S. economy has shifted, moving away from manufacturing and towards being an information and service economy. The mid-1980s, for instance, were punctuated by news of the closures of major steel manufacturers, including Homestead Works, Aliquippa Works, and Duquesne Works in Pittsburgh, PA, and Republic Works in Youngstown, OH. The closures were part and parcel of a period of massive deindustrialization. Between 1984 and 2004, the U.S. economy lost between 6 and 7 million manufacturing jobs that provided reliable and high-paying employment with good benefits for millions of working-class Americans.

The move away from manufacturing had a significant impact on America’s working class. Real wages of the median Americans with a high school diploma or less (a common measure of “working class”) declined by 11% between 1979 and 2019, while those of the median worker who had finished college increased by 15 percent. Many industrial communities, especially across America’s “Rust Belt,” experienced significant disinvestment and fell into blight. These economic shifts, both in the Rust Belt and nationwide, took a devastating toll. They pushed working-class men’s labor force participation down and led to declines in religious and secular expressions of community life in areas hit hardest by deindustrialization. Families not only broke apart but failed to form. In the wake of this economic dislocation and social breakdown, deaths of despair—that is, deaths from drug overdoses, suicides, and alcoholism—surged among working-class women and especially men.

The transformation of the American economy has been especially impactful on working-class men. As manufacturing receded, employment in service industries surged, especially in healthcare, financial, and information services. Many of these service jobs require a college degree. And most of the significant growth in jobs that do not require a college degree has been concentrated in industries and occupations that are female dominated. Since 1990, the healthcare industry alone has added roughly 9 million jobs to the US economy. Nearly 80% of Americans who do not have a college degree and work in healthcare are women.nbsp;In fact, declines in real wages for working-class workers were concentrated among men; working-class women have seen their real wages rise since 1979.

Over this same period, Americans have also experienced a significant reduction in marriage and family stability. Since 1970, the marriage rate has fallen by more than 60% to the point where only about 1 in 2 adults are married. Declines in marriage and family stability have been especially precipitous for working-class Americans since 1980. For instance, only 39% of non-college-educated Americans ages 18-55 are married, compared to 58% of college-educated Americans.

Our hypothesis in this Institute for Family Studies (IFS) report is that the nature and character of work play a key role in affecting male marriageability. We contend that features of work like job stability, predictable hours, good benefits, and high pay help men to flourish and, in turn, elevate their appeal as husbands. Moreover, we note that class divides in marriage today are driven in part by differences in the character of work, with college-educated men generally benefiting, in terms of marriage and family formation, from jobs that are more stable, predictable, higher status, and remunerative. But we also suspect that the character of work varies among working-class men themselves, such that some jobs among working-class men are more likely to facilitate marriage and family formation than others.

In this report, we examine family formation among working-class men, defined here as men without college degrees, within the context of distinct employment environments. We also examine differences in married family formation rates—measured here in terms of being married with children at home—between working-class and college-educated men, and we investigate the extent to which these differences might be explained by differences in “good job” variables—primarily differences in pay, benefits, and stability. We then explore differences in the rates of married family formation among working-class men by industry and estimate the extent to which differences across industries are explained by the same “good job” variables. We conclude with a discussion of how public policies might better support working-class men in their jobs to improve their family prospects.

Part 1: Family Formation Among Working-class Men

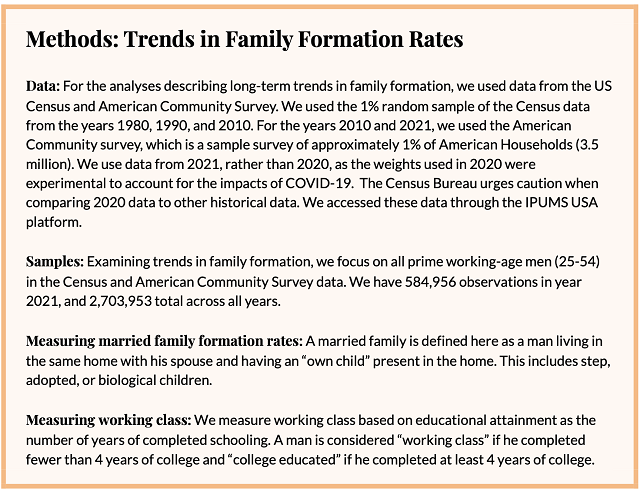

Trends in family formation rates

In this section, using historical Census data from 1980-2021, we discuss recent family formation trends among working-class men. Working class throughout this report is operationalized as completion of less than a college education. Here, college education is defined as completion of at least four years of college. Importantly, this is slightly different than the operationalization of “working class” because the measures of educational attainment in historical Census data are slightly different from the CPS data used in subsequent analyses.

There is ample evidence that college-educated Americans are more likely to get married, stay married, and avoid having children out of wedlock. This is partly because more educated men and women have more stable incomes, more shared assets, greater civic supports for their marriages, and networks that are dominated by married peers, as Wilcox argued in Get Married.

However, this has not always been the case. In fact, before the 1980s, men who did not complete college had higher rates of married family formation compared to those who did complete college. In our analysis of Census data, we found that in 1980, 59% of all prime working-age men (ages 25-55) who did not complete college were married with children living in their homes, compared to 55% of men who did complete college.

Over the course of the next 40 years, all men in America were increasingly less likely to be married and living with children. By 2021, only 37% of prime working-age men were married living with children compared to 58% in 1980 (Figure 1). But the overall decline in married family formation was more significant for men who had not completed college. Over the last 40 years, men who had not graduated from college were now actually less likely than college-educated men to be married and living with their own children. By 2021, 34% of non-college-educated, prime working-age men were married and living with their own children compared to 44% of college-educated men.

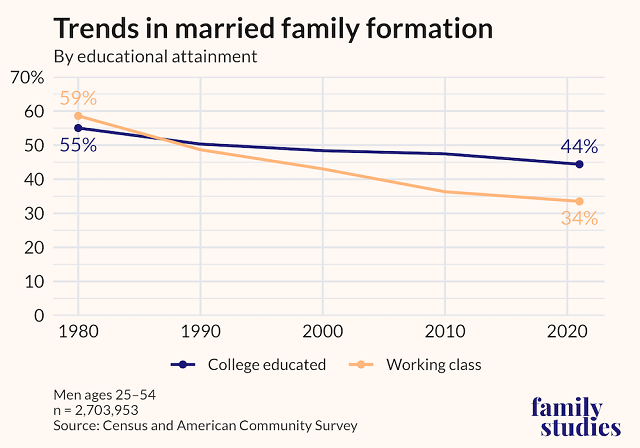

We examine more closely family formation rates among working-class men ages 25-55 in 2021 (Table 1). We found that working-class men (33.50%) were much less likely to be married with children living in their homes compared to college-educated men (44.39%). At the same time, they were much more likely to cohabit with children in the home (3.44% vs. 0.93%) and to be living with no partner and without children (41.36% vs. 31.83%).

Part 2: Examining Married Family Formation by Class and the Impact of Good Job Variables

Married family formation rates by class

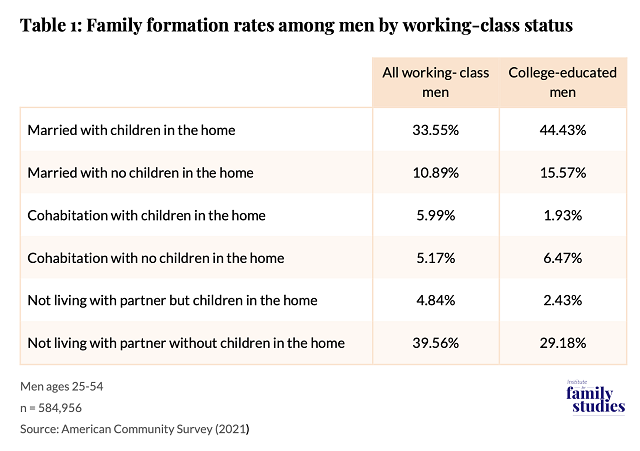

This section compares all college-educated versus working-class men. We are interested primarily in the links between class, workplace environment, and family status. For this analysis, we use data from the Current Population Survey from years 2021-2024. We used regression models to estimate predicted probabilities of having a married family by education, which we view as a proxy for class. In our sample of 113,656 prime working-age men, we find that working-class men were 8 percentage points less likely than college-educated men to be married and living in the home with their children (Table 2). Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A3.

Mediation of differences across class by good job variables

We then examine the extent to which differences in married family formation across classes might be explained by differences in the types of jobs that working-class and college-educated men hold (i.e., good job variables). To determine the extent to which differences could be explained by good job variables, we performed a mediation analysis using the Barron and Kenney framework. To do this, we must first establish that good job variables are associated both with class and married family formation. If so, we can test the mediation impact of good job variables on marriage formation rates.

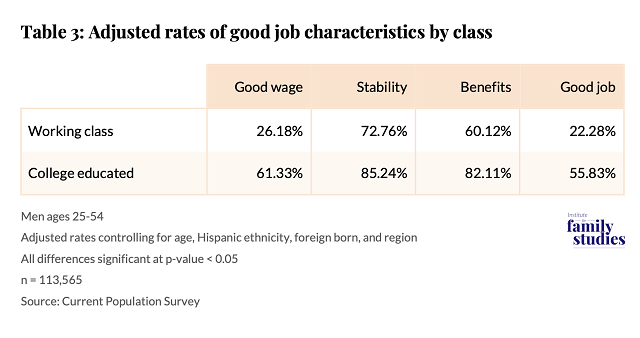

We first compare good job variables across working-class and college-educated men. We find significant differences across classes. Most notably, a majority of college-educated men (61.33%) make a “good wage” (i.e. >$60,000 per year) compared to a minority of working-class men (26.18%). College-educated men are also much more likely to have stable jobs. They are also about 20 percentage points more likely than working-class men to have employer-sponsored health benefits. They are much more likely to have all three good job characteristics at their current employer (Table 3). Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A4.

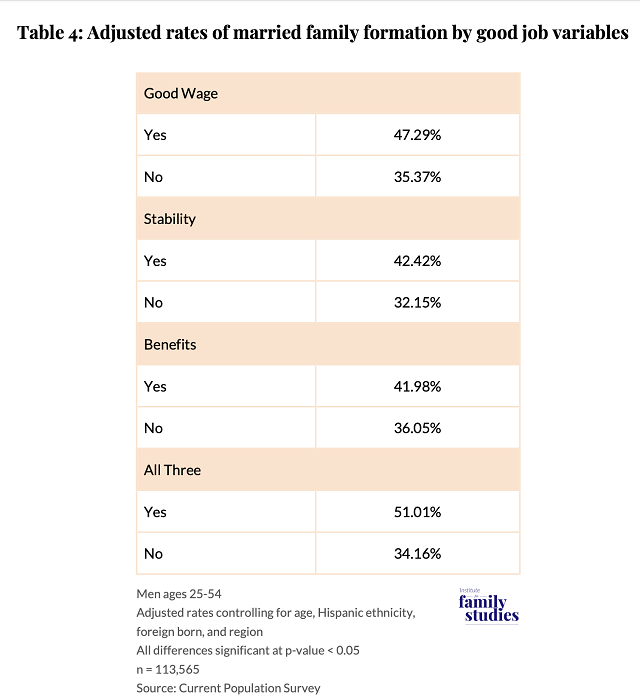

These good job characteristics are also correlated with married family formation rates. We find that those with good job characteristics are much more likely to be married family men. Those with all three of these good job characteristics are 17 percentage points more likely than those who do not have all three of these characteristics to have a married family (Table 4). Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A5.

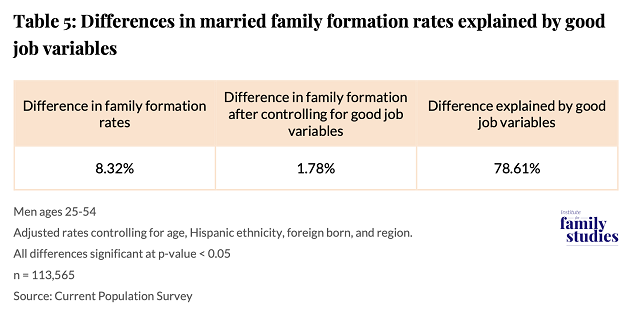

Finally, we examined the extent to which the good job variables mediate the relationship between class and family formation rates. Table 5 shows that good job variables are in fact a significant meditator between class and married family formation. These good jobs variables explained nearly 80% of the adjusted differences in married family formation rates by class (Table 5). This is a striking finding. It underlines the ways in which the character of college-educated men’s jobs probably helps explain why they are markedly more likely to get and stay married than working-class men. Of course, we cannot determine the direction of causality here. All that we can say is the class divide in marriage between college-educated and working-class men is closely tied to the class divide in the character of men’s work. Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A3.

Part 3: Examining Married Family Formation by Industry Among Working-class Men

Married family formation rates by industry

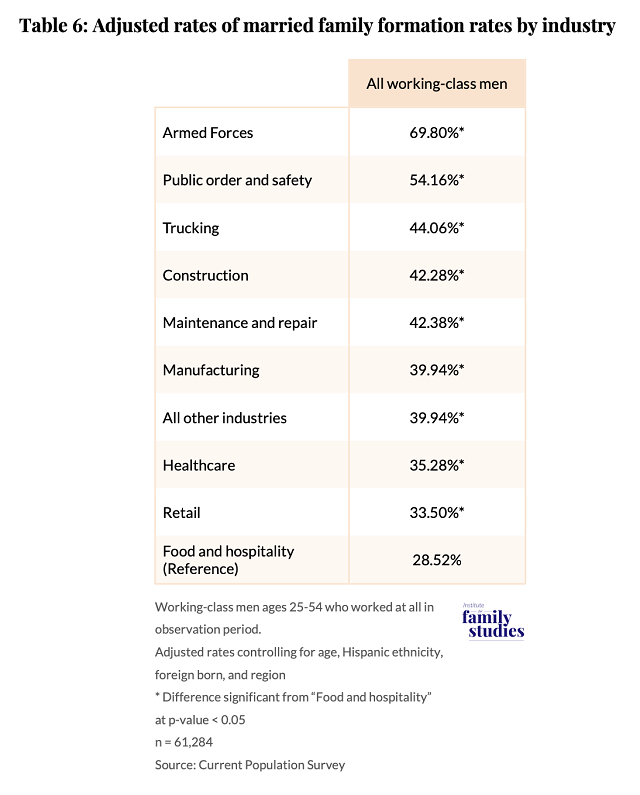

Patterns of married family formation for working-class men differ by employment industry. In this section, we focus exclusively on men who report having worked during the observation year. Only those who worked at some point during the observation year will have data on primary industry. For this analysis, we use data from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS) from years 2021-2024. Table 6 indicates wide variation across industries in terms of the rates of married family formation for working-class men. The highest married family formation rates among working-class men are in the armed forces and public order and safety, followed by trucking, construction, and maintenance and repair. The high rates of married family formation in the armed forces are consistent with earlier research indicating that the armed forces continue to support marriage and family life. Surprisingly, manufacturing falls in the middle. By contrast, the lowest shares of married family formation for working-class men are in healthcare, retail, and food and hospitality. Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A6.

Mediation of differences across industries by good job variables

For working-class men, there is clearly variation between industry and family structure. How much are differences in married family formation rates across industries linked to differences in “good job” variables, including pay, health insurance benefits, and stable employment? In this section, we take up this question.

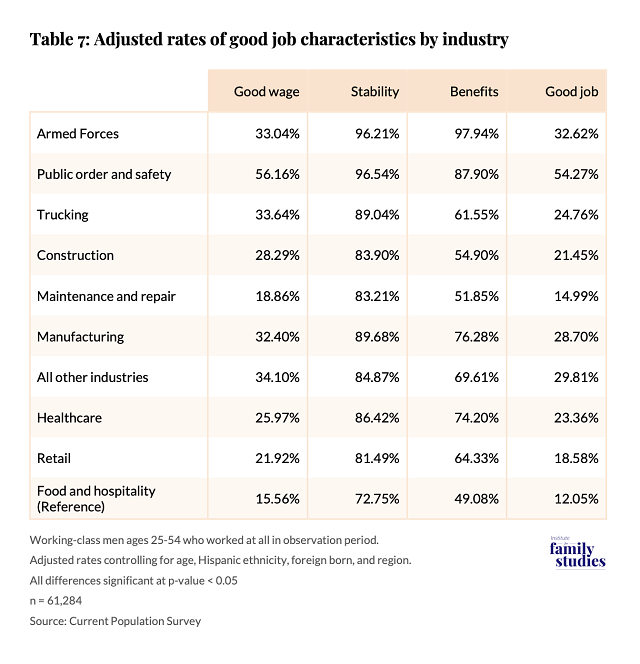

To determine the extent to which differences could be explained by these good job variables, we again perform a mediation analysis using the Barron and Kenney framework. In examining the relationship between industry and good job variables, we find that some industries have more good job characteristics than others, as Table 7 indicates. Public order and safety, armed forces, trucking, and manufacturing have higher rates of good wages, while retail, food and hospitality, and maintenance and repair have significantly lower rates. Likewise, there were significant differences in job stability across industries with public order and safety, manufacturing, armed forces, and trucking enjoying the highest rates of stability, while food and hospitality had the lowest. In terms of benefits, public order and safety, manufacturing, trucking, healthcare, and, especially, armed forces had the highest rates of uptake of employer sponsored health insurance, while construction, food and hospitality, and maintenance and repair had the lowest. Again, our results here are indicative of the marriage- and family-friendly character of military jobs. Overall, public order and safety, manufacturing, construction, and trucking had the highest rates of all three good job characteristics, while retail, maintenance and repair, and especially food and hospitality had the lowest rates. We show the detailed regression results used to generate these adjusted rates in Appendix Table A7.

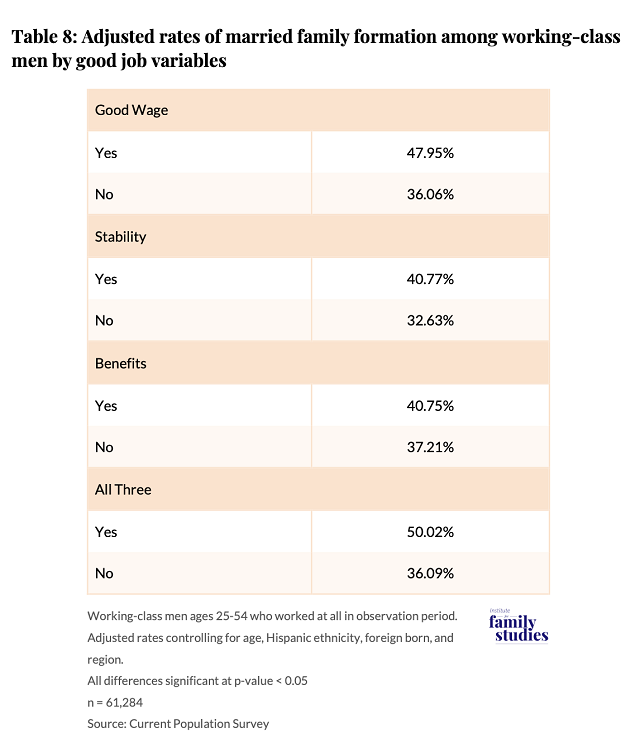

We also examined the relationship between family formation rates and good job variables within the Part 3 sample. Table 8 indicates that each of the good job variables is consistently correlated with higher rates of married family formation for working-class men. Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A8.

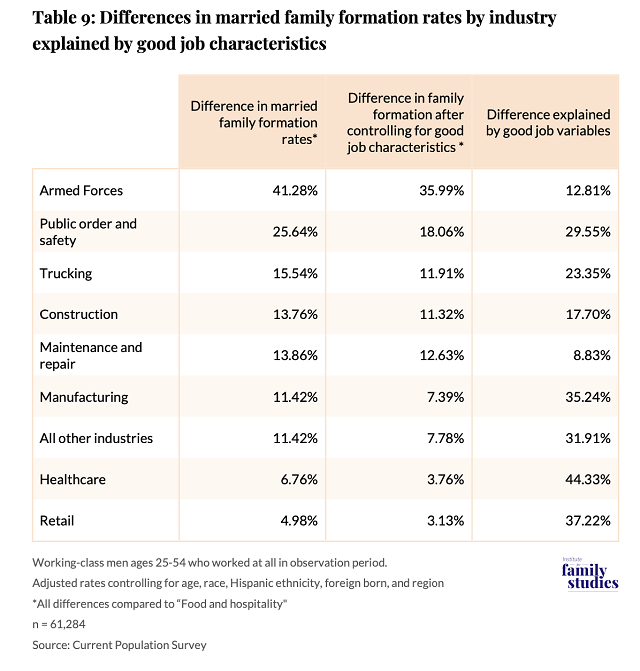

Finally, we examined the extent to which the good job variables mediated the relationship between industry and married family formation rates. Table 9 shows that good job characteristics are in fact a mediator between industry and married family formation for most sectors of the economy, but the amount of difference in married family formation rates explained by good job characteristics varies significantly across industries. The good job characteristics explain between 8-44% of the difference in married family formation between each of the industries compared to the food and hospitality industry. Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A6.

Conclusion

This Institute for Family Studies report suggests that both the nature and character of men’s work play a major role in determining whether men marry and form families. One big reason that working-class men are less likely to form married families seems to be that they have lower quality jobs—jobs marked by less income, less stability, and lower benefits. These findings must, however, be interpreted with caution. We do not show a direct causal relationship between good jobs and married family formation here, though we do show that having a good job is linked to men’s marital and family fortunes. To wit: prime-aged men with good jobs are markedly more likely to be married with children than men in lower quality jobs. So, consistent with the broader literature on work, men, and marriage, we think that access to good jobs increases the odds that men marry and form families.

Moreover, we document that differences in job quality help explain, statistically, almost 80% of the differences in the married family formation rates between working-class and college-educated men. This is a striking finding. Class differences in men’s work are clearly tied to class differences in marriage and family formation. The clear implication here is that men are more likely to be married with children when they are well paid, their jobs are stable, and their benefits are good.

Moreover, among working-class men, the findings of this IFS report suggest that having a good, working-class job appears to help explain differences among working-class men in married family formation rates across industries. More concretely, the fact that sectors like public order and safety, trucking, and manufacturing often have higher pay, greater job stability, or better benefits may help explain why men in these jobs also have comparatively high levels of married family formation. Undoubtedly, the good job characteristics that are more likely to define these sectors help explain why men who serve in these jobs are the working-class men most likely to be married with children.

In our analysis of industries and married family formation among working-class men, our good job variables do not explain all the difference in married family formation rates across industries among working-class men. There are likely other differences in job characteristics across the industries that we could not measure that may influence married family formation. We were particularly struck by the exceptionally high rates of family formation for men serving in the armed forces, which are not completely explained by our specific measures of good job characteristics. It may be that the military has a culture that is more friendly to marriage and family formation, or that the extra housing benefits (which we did not measure) extended to married service members make marriage more attractive to men in the military.

We also observed that healthcare, retail, and food and hospitality had lower levels of married family formation. This could be because many of these jobs are marked by erratic and unpredictable schedules that make it difficult to forge a strong and stable family. Many cities and states have attempted to alleviate this problem by legislating predictable schedules with some success.Some sectors—like food and hospitality—may also be associated with a culture of late nights and substance use that is not conducive to forming strong and stable families. Patterns like these undoubtedly help explain the clear differences we document between different sectors of the economy and trends in working-class men’s family formation.

Likewise, we also recognize an important selection effect is likely at play in our analysis. It is possible that these findings can also be explained by the fact that men who are best able to obtain good jobs also tend to have personal traits and social skills that are consistent with the ability to find a mate and form a family. Certain sectors—the armed forces, for instance—may attract and retain men who are especially reliable and responsible, and these underlying traits may also make them more attractive husbands and fathers. Moreover, working-class men are also likely to seek out better employment once they are married and have children.Marriage and family motivate men to seek out certain kinds of work, as well.

In conclusion, this Institute for Family Studies report shows that men who are employed in stable, good-paying jobs with decent benefits are markedly more likely to be married with children. Given this social fact, we think that employers and policy makers should aim to increase the share of high-quality jobs to American young and middle-aged adults, even as educators and policy makers seek to increase the share of young adults who are prepared to fill these jobs. When it comes to fostering work that is both more humane and remunerative, this requires taking a page from both the progressive playbook—e.g., Seattle’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance, which requires large businesses in the service sector to make workers’ schedules more predictable—and the conservative playbook—e.g., reducing regulatory burdens to expanded gas and oil exploration, thereby opening up more high-paying jobs in the energy sector. The exceptionally high rates of marriage and family formation among working-class men serving in the military also suggest that public policies designed specifically to help married families are also worth considering. Doing all these things might very well boost the fortunes of not only American men but also American families.