Highlights

- Even black women raised by the richest parents are less likely to be married or cohabiting in adulthood than white women who grew up poor. Post This

- In general, black women are only about half as likely as white women to be partnered; combined with the fact black women tend to partner with lower earners, the gap grows to about 60%. Post This

- The racial gap in EIFP tends to be bigger in places with higher overall inequality, and women marry higher-earning partners when sex ratios skew in their favor. Post This

Romantic partnerships have many benefits, but one is especially straightforward: Two people tend to make more money than one. A recent study from Census Bureau researchers breaks down how these benefits differ across racial groups, with a focus on what white and black women gain from marriage and cohabitation—and how this income contributes to economic mobility.

By combining IRS tax-return data with the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, the authors can match individuals’ childhood family incomes with their later romantic pairings and earnings. Because men tend to be older than their partners, the researchers use a sample of men born between 1976 and 1983 and women born between 1982 and 1986, and they focus on marriages and cohabitations from when the men were ages 31-35 and the women were ages 28-32.1

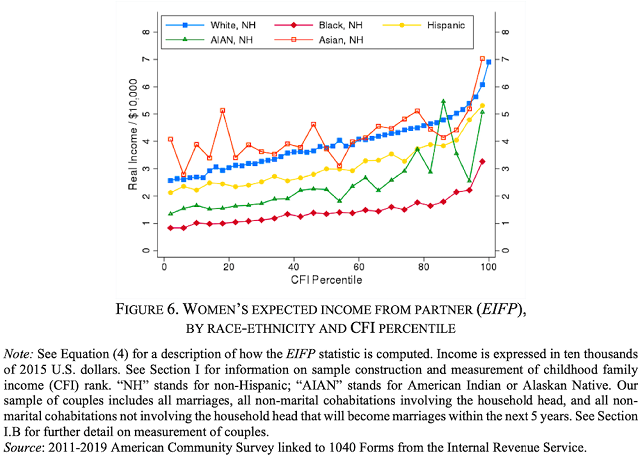

Their key statistic is called the “Expected Income from Partner” (EIFP): If a woman grew up with a certain family income, and is from a certain racial group, how much income can she expect, on average, to gain from a romantic partner?

There are two different dimensions to this: the “extensive” margin, meaning how likely the woman is to partner at all (for the “income from partner” is zero if there is no partner); and the “intensive” margin, meaning how high-earning any partner is likely to be.

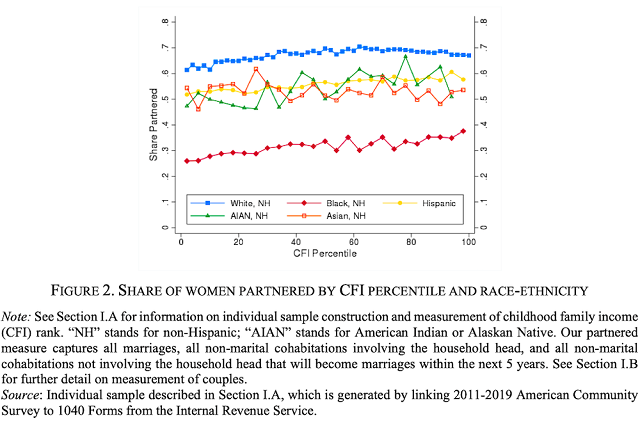

The extensive-margin gaps are especially pronounced by race. As this chart shows, women of all races are a bit more likely to be partnered if they grew up in richer households (CFI stands for “childhood family income”), but even black women raised by the richest parents are less likely to be married or cohabiting in adulthood than white women who grew up poor.

In general, black women are only about half as likely as white women to be partnered. When this is combined with the fact black women tend to partner with lower earners, the gap grows to about 60 percent. Once again, the racial gap is even more stark than the gap by childhood family income. Holding childhood family income constant, white women’s EIFPs are higher than black women’s by more than $10,000, and the gap is greater among women who grew up in richer families.

The authors also run a few counterfactual simulations. As work from Raj Chetty has also found, there isn’t much of a gap in personal income between white and black women who had the same family income in childhood (i.e., they are similarly economically mobile)—so eliminating that gap makes only a small difference. By contrast, the mobility gap shrinks by 85% when their partner incomes are equalized.

The paper also explores some dynamics in local marriage markets. For instance, the racial gap in EIFP tends to be bigger in places with higher overall inequality, interracial marriage is more common in places with lower residential segregation, and women marry higher-earning partners when sex ratios skew in their favor (i.e., when women are scarce relative to men, which differs by race owing to gaps in incarceration and mortality). Dramatic changes to these variables—in a simulation, the authors “equalize race-specific sex ratios, eliminate racial-ethnic segregation, and reduce income inequality to that of Sweden”—could eliminate 40% of the racial EIFP gap.

For what it’s worth, I think the authors could have done even more through simulating counterfactuals in marriage markets. For instance, what if black women married as often as white women, but married the men available to them in their current situation? Or, what if the racial gaps in men’s incomes disappeared, but the racial gap in marriage rates remained unchanged? There are a lot of different variables in play—marriage rates, wages, housing policy, income redistribution, etc.—and it’s hard to say what policies could have the greatest effect without a more granular decomposition of the mobility gap.

That said, the paper is an impressive achievement, combining extensive survey data with tax returns to answer an important and underexplored question. Hopefully it will inspire more work like it.

Robert VerBruggen is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

1. This means they don’t consider folks who got married later; they also exclude some folks whose ACS data couldn’t be matched to IRS records, and some couples with wide age gaps.