Highlights

- Fewer divorces granted to wives in the UK accounts for 95% of the reduction in all divorces since the 1980s. Post This

- Whatever way you look at it, the trend in divorce rates is dominated by wife-granted divorces in the first decade of marriage. Post This

- For me, the most plausible reason for fewer wife-granted divorces lies in reduced social pressure and expectation to marry. Post This

As in the United States, most people here in the UK know that divorce rates have risen since the 1960s. But when I tell them divorce rates have fallen nearly back to 1960s levels, the response is usually surprise. This is followed quickly by, “It must be because fewer people are getting married.”

It's certainly true that fewer people are getting married, but the divorce rate is falling, even factoring in lower marriage rates. And this story varies a lot by gender.1

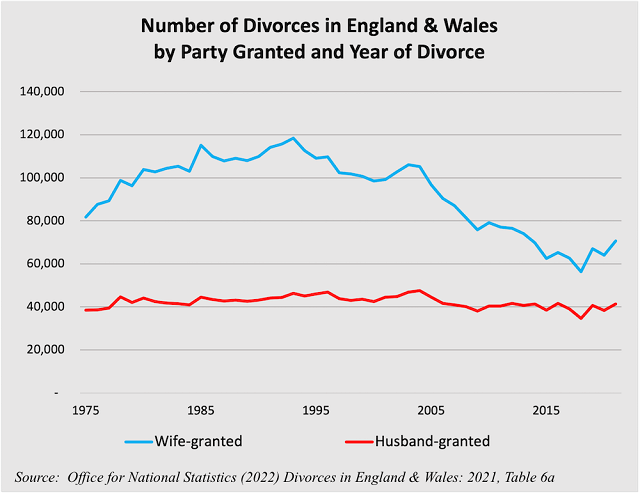

Let’s have a look at the number of divorces broken down by whether the wife or husband was granted divorce. Until the law changed in April 2022, only one party in England and Wales could file for divorce and be granted divorce. There were exceptions, but these were rare.

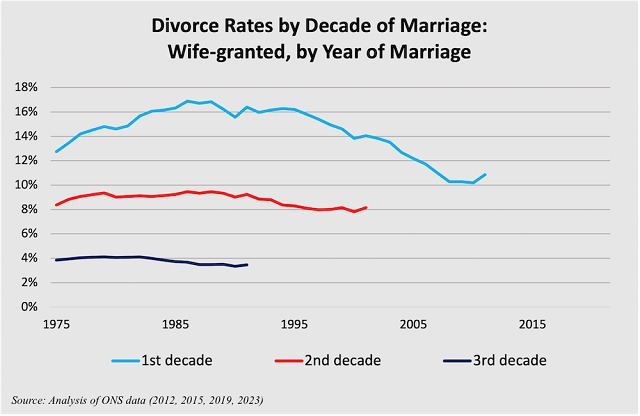

The extraordinary thing is that almost all the long-term variation in divorce, in both numbers and rates, concerns wife-granted divorces. An earlier version of the chart below is what sparked my interest 12 years ago when I first came across this phenomenon. I think you’ll agree this is remarkable.

Comparing 2021 with 1986 for example—the wedding year that has turned out to have the highest proportion of divorces—there were 39,276 fewer divorces granted to wives, yet only 2,112 fewer divorces granted to husbands. Fewer divorces granted to wives thus accounts for 95% of the reduction in all divorces since the 1980s.

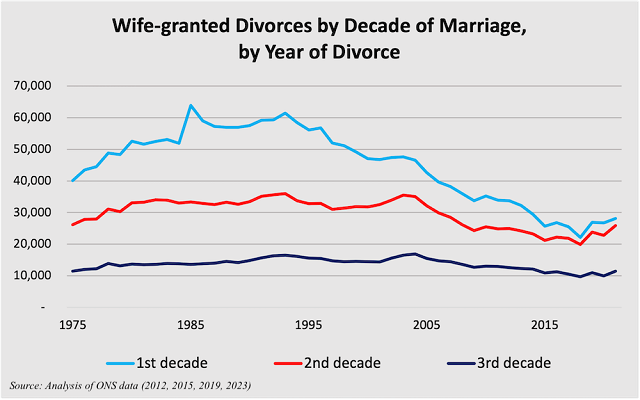

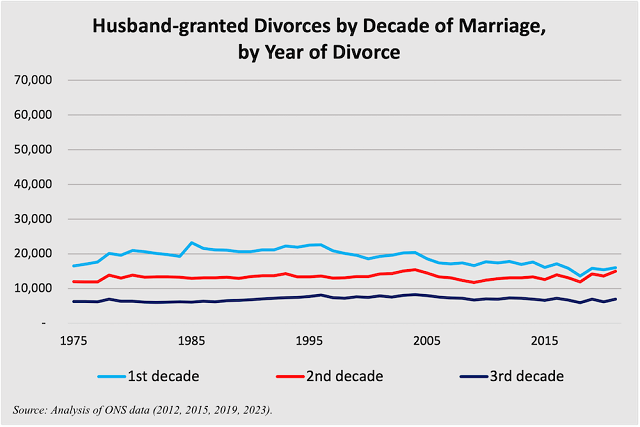

Our Office for National Statistics (ONS) also breaks down annual divorce data by party granted, whether a wife or husband, but they don’t publish this routinely. I have commissioned them four times to keep these numbers up to date. The next two charts make the distinction even more stark, showing that the big long-term trends in divorce are mostly concentrated not just among wives but among wives in their first decade of marriage.

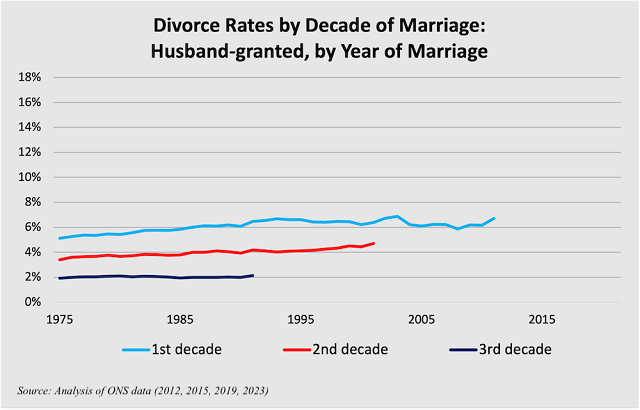

I convert this into divorce rates, rather than numbers, by comparing one-year divorces with weddings in the previous year, two-year divorces with weddings two years earlier, and so on. This is the same method used by ONS. I can then look at the proportion of people marrying in any wedding year and follow the trend in their actual divorce rate over time. This gets rid of the complaint that lower divorce numbers are an artifact of fewer people marrying.

Now the distinction becomes even more stark. Compared to the wedding cohort with the most divorces so far, which was 1986 and coincidentally my own wedding year, the most recent wedding cohorts experienced a drop of 6.7% fewer wife-granted divorces in their first decade of marriage, 1.7% fewer in their second decade, and 0.3% fewer in their third decade. In contrast, husband-granted divorces have risen slightly by 0.2%, 0.5%, and 0.0%, respectively. Whatever way you look at it, the trend in divorce rates is dominated by wife-granted divorces in the first decade of marriage.

In case you wondered about the recent blip, it’s almost certain that this is due to faster processing of a divorce backlog in 2022 rather than an actual increase in divorce rates. What’s going on?

The key issue is that this is a highly gendered trend. The answer can’t be that couples are marrying later. If both parties are older and wiser, you’d expect fewer wives and husbands to file for divorce. It is also unlikely to be about economic or housing pressures. Arguments about money affect both parties.

Two plausible explanations account for the rise in wife-granted divorce rates in the 1970s and 80s. The first is from Gary Becker’s classic theory of the family as a “small factory.” As women gain economic autonomy and wages rise, the economic benefit of marriage for a woman declines. This helps account for fewer marriages and more wife-granted divorces.

The second is a consequence of the emergence of cohabitation. The inertia of living together encouraged more fragile couples to marry rather than split up. Research on several different samples in the US by Galena Rhoades, Scott Stanley, and Howard Markman has shown that a significant proportion of men who cohabit before getting formally engaged are less dedicated when they do marry. The likely result is more wife-granted divorces. Alas, these arguments run out of steam in the 1980s and don’t explain the reversal in trend from the 1990s onwards.

For me, the most plausible reason for fewer wife-granted divorces lies in reduced social pressure and expectation to marry. Imagine a man who married in the 1980s. “Do the right thing,” say his friends and family. “Make an honest woman of her. Tie the knot.” So he enters marriage under social pressure because he ought to marry, without ever fully buying into it. His sense of dedication is weaker than that of his wife. But if things are good, he is broadly content with his new arrangement.

Over time, and perhaps with the arrival of a baby, inevitable little conflicts emerge between him and his wife. Instead of dealing with them responsibly, he feels less constrained in the way he behaves because he knows he never really bought in to a long-term plan in the first place. But just as he was sucked into marriage without making the decision for himself, inertia and indecision keep him in the marriage.

Quite soon his behavior appears increasingly indifferent and disrespectful to his wife. After only a few years, she is all too aware of his indifference. Fed up with treading on eggshells around him, she pulls the plug.

Now imagine a man who married in the 2000s. He is under no such family or social pressure to marry. When he does commit to his wife and his marriage, he commits because he wants to do so. When the conflicts emerge, he knows that he has a responsibility to sort them out. There is a long-term plan at stake here. His wife appreciates the effort he makes to sort things out and thus knows he is fully committed to her. Serious difficulties are much less likely to materialize in these early years and she is much less likely to think about divorce.

So here’s my conclusion in a nutshell. In the 1980s, plenty of couples married because they wanted to marry. But plenty also married out of social pressure and expectation. This latter group included less-committed men whose wives eventually had enough. Today, most couples marry because they want to marry. In this case, fewer marriages are a part of the picture because there are now fewer who marry because they ought to marry. The result is a decline in wife-granted divorces in the early years of marriage.

More committed men, happier wives; happier family lives, fewer divorces.

Harry Benson is research director for Marriage Foundation UK and a PhD student of marriage at the University of Bristol.

1. Note that this analysis concerns heterosexual marriages and divorces. Same-sex marriage was introduced in the UK in 2014 and the first same-sex divorces took place in 2015. It’s impossible to say anything meaningful about same-sex divorce trends as data is too recent and numbers are relatively small.