Highlights

My last blog ended with two points: Congress has more work to do if it wants to eliminate the marriage penalty in the tax code, and there are more severe marriage penalties in the welfare system that need to be addressed. As I explained last time, fewer taxpayers will encounter marriage penalties in 2018 because of changes in the way tax liabilities will be calculated in 2018 on line 44 of IRS Form 1040 (using the 2017 form).

However, tax credits are determined after the tax liability is calculated.

For example, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), also called the Earned Income Credit, is one of those tax credits, and it is refundable, meaning that taxpayers who qualify can receive the credit even if they end up paying no income taxes at all. In other words, the tax system provides them with subsidies. The EITC makes the U.S. income tax system truly a negative income tax system, and it is one of the largest means-tested welfare programs, and the largest cash assistance program in America.

The EITC introduces its own marriage penalties, which can negate the elimination of marriage penalties in the computation of tax liabilities. For example, if two childless persons each earn only $11,000 a year, they would lose $658 in the EITC if they marry. If they have children, the penalties are more severe.

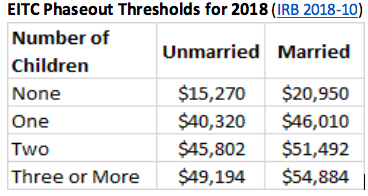

Because of the phaseout characteristic of the EITC, taxpayers qualify for the credit far above what would be considered impoverished levels of income. For unmarried individuals, they can receive the credit with up to $40,320 in earnings if they have one child, up to $45,802 if they have two children, and up to $49,194 if they have three or more children.

When it comes to non-Tax Code means-tested programs, it is more difficult to define marriage penalties. If we define them the same way as with taxes—the simple difference in the benefits from the means-tested assistance program when the couple is married and not married—then there will almost always be marriage penalties when both persons have earnings. The reason is simple enough. When the earnings of two persons are summed together, it increases their means and almost always lowers their benefit.

This fact alone incentivizes the misreporting of circumstances. For example, benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), more commonly known as the food stamp program, should be the same for a couple whether they are married or cohabit. Food stamp rules stipulate that benefits are determined based on living together, purchasing food together, and preparing meals together. However, the rule is not uniformly enforced by the states, and recipients are incentivized to report themselves as purchasing food and preparing meals separately because they will receive more in benefits. This practice discourages marriage because married couples—unless they are separated—are regarded as a single SNAP household.

Misreporting of circumstances is difficult to control, and it requires the states, who administer the program, to be vigilant in enforcing it. However, the states do not have a financial incentive to control costs, because the federal government pays the entire cost of the benefits issued. States share only in the administrative costs of running the program.

Therefore, the federal government needs to issue explicit guidelines to the states to enforce this intention of the law. Still, it will be difficult to eliminate all incidences of misreporting, such as when a woman, with or without children, is living with her boyfriend who is not on the lease and uses another address as his permanent address.

Alternatively, Congress could redesign SNAP to require states to match the federal dollars of benefits issued. This alternative construct would incentivize states to do a better job at enforcing this provision of the law, although this alternative promises to be controversial.

A more effective approach, that is not mutually exclusive, would be to revamp the maximum allocation tables and income deductions to favor—or at least not penalize—married couples. Currently, a cohabiting couple and a married couple are treated the same. If the maximum allocation tables and deductions were redesigned to favor the married couple, it would incentivize marriage for those who report their circumstances honestly.

Finally, when it comes to marriage penalties, it is the cumulative impact that matters. It is necessary to look at the complete picture as it impacts real people. Analyzing one tax program or one means-tested program individually is not enough, although the solution will likely come from an incremental approach of fixing one program at a time. For more detailed analysis, check out my reports for the Georgia Center for Opportunity that used computer programming to calculate marriage penalties and bonuses over a matrix of wage combinations, giving a more complete picture of the penalties and the severity of those penalties.

The best way to eliminate these cumulative penalties would be for Congress to allow states to systemically reform welfare programs through consolidation and coordination, while mandating that those reforms work toward eliminating marriage penalties. Congress can start this process with SNAP by inserting such language into the 2018 Farm Bill before sending it to President Trump.

Erik Randolph is a contributing scholar to the Georgia Center for Opportunity (GCO), a senior fellow with the Illinois Policy Institute, an adjunct instructor of economics for York College of Pennsylvania, and owner of Erik Randolph Consulting. His marriage penalty paper “Deep Red Valleys” can be found here.