Highlights

- Congress has more work to do if it is serious about completely eliminating the marriage penalty. Post This

- One might assume that individuals or couples who do not earn enough money to pay income taxes or to even fall within the lowest tax brackets will not encounter a marriage penalty. But this is simply not the case. Post This

The additional tax burden a couple must pay if they are married is known as the marriage penalty. It incentivizes cohabitation and disincentivizes getting married. Now, however, because of Congressional action, fewer taxpayers will be subject to this penalty.

Signed into law by President Trump last December, Public Law 115-97 extended the number of taxpayers who will not be subject to the marriage penalty. The following characteristics virtually guarantee that a couple will not pay a marriage penalty in 2018:

- Neither partner can claim children as dependents.

- Neither partner qualifies for the Earned Income Tax Credit.

- Neither partner qualifies for food stamps or any other welfare program.

- The combined income does not exceed $600,000.

For all others, however, the chances are good that the marriage penalty still applies.

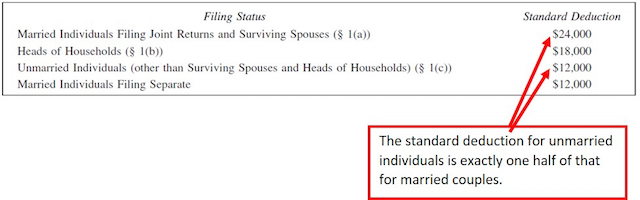

That’s because, in addition to other changes, the new tax law eliminated deductions for personal exemptions and continued the practice of keeping the standard deduction for unmarried individuals (with no children) as equal to one half of the amount for married couples who file jointly.

Revised Standard Deductions for 2018 (Internal Revenue Bulletin “IRB” 2018-10)

Keeping the standard deduction for unmarried individuals at one half of that for married couples is an important first step in eliminating the marriage penalty. It equalizes the calculation for taxable income. In other words, if the standard deduction for unmarried individuals were more than half of that for married couples, then less of unmarried partners’ incomes would be subject to income taxes. Likewise, if the standard deduction for individuals were less than half, then more of the unmarried partners’ incomes would be subject to income taxes.

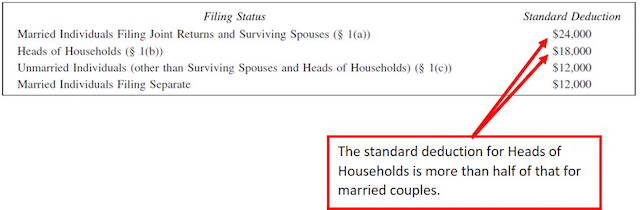

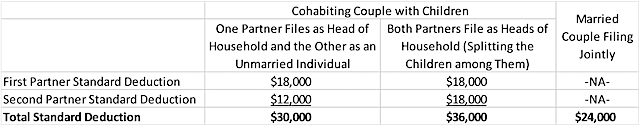

However, if a couple has children, they still get a higher standard deduction from cohabiting than from being married. The reason? Unmarried individuals with children who qualify as dependents for tax purposes do not file their tax returns as unmarried individuals. They file their returns as Heads of Households.

Revised Standard Deductions for 2018 (IRB 2018-10)

The standard deduction for Heads of Household is more than half of that for a married couple. In fact, it equals 75% of the deduction for a married couple. If a couple has one child to claim as a dependent on its tax form, then it will have $6,000 more in income that is not subject to federal income taxes if they cohabit. If the couple has two children, they can split the children among the two tax returns and have $12,000 more in income that is not subject to federal income taxes.

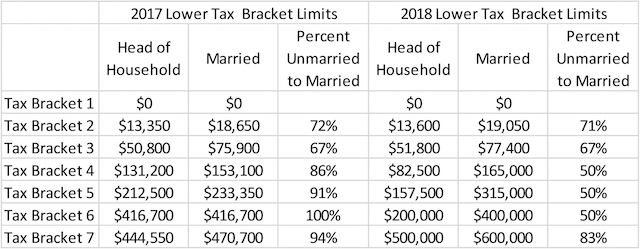

One important change Congress made in Public Law 115-97 is to extend the number of tax brackets where the income thresholds for unmarried individuals are equal to half that of married couples. Previously, only the first two tax brackets followed that rule. Now six of the seven tax brackets do.

Source: IRB 2016-45 and IRB 2018-10

For taxpayers filing as Heads of Households, the new tax law reduced three bracket limits to equal half of the thresholds for married couples. Although this change moves toward eliminating the marriage penalty for those with children in those three tax brackets, it does not actually get there. Recall that cohabiting couples have less of their income subject to federal income taxes rate than do married couples.

Source: IRB 2016-45 and IRB 2018-10

Both rules for standard deductions and tax bracket income thresholds boil down to two lines on IRS Form 1040: lines 43 and 44 (for tax year 2017). Line 43 is the taxable income after adjustments and deductions, including the standard deduction. Line 44 is the tax liability based on the tax tables using the seven tax brackets before credits are considered.

Congress has more work to do if it is serious about completely eliminating the marriage penalty. The standard deductions for non-married individuals, as well as the tax bracket thresholds, must be equal to half of those for married couples in all cases, not just in some cases.

Finally, one might assume that individuals or couples who do not earn enough money to pay income taxes or to even fall within the lowest tax brackets will not encounter a marriage penalty. But this is simply not the case because it ignores the more severe marriage penalties that still exist in the welfare system, which will be the topic of my next blog.

Erik Randolph is a contributing scholar to the Georgia Center for Opportunity (GCO), a senior fellow with the Illinois Policy Institute, an adjunct instructor of economics at York College of Pennsylvania, and owner of Erik Randolph Consulting. His marriage penalty paper, “Deep Red Valleys,” can be found on the GCO website.