Highlights

As parents, we are hardwired to protect our kids. Every day, we make investments in their health, safety, and long-term well-being: we teach them about road safety, help them with their homework, send them to the best schools possible, encourage them to exercise, take them for medical check-ups, get them vaccinated against childhood diseases, and educate them on the dangers of drugs and alcohol. The list is endless—or at least it often feels that way.

All of these things matter a lot. But the single biggest risk to the long-term well-being of most of our children today is their diet. The question every parent should ask themselves is: am I doing enough to create a healthy food environment at home and build the healthy eating habits that will support good metabolic health for life?

Until 2018, I thought I was doing a good job supporting my family’s health with good nutrition. I love to cook, so home-cooked breakfasts and dinners were part of family life most days. We bought mostly organic fruit and vegetables. Most days, we got close to our “five a day.” We limited cookies, candy, and sodas. Fast food stops were restricted to long road trips a few times a year.

Then one of my sons had a crisis. He could no longer tolerate the side effects from his ADD medication and was suddenly failing most of his high school classes. I did what I always do: hit the books (or rather, the internet). I took a deep dive into the scientific literature on neurological disorders, trying to find a way to help my son. I stumbled across research, new and very old, on the benefits of a different way of fueling the brain and body. Specifically, I discovered the ketogenic or “keto” approach to nutrition, which limits carbohydrates and ramps up the fats.

We needed a new approach, so decided to give it a go. (I should add that I did all this by stealth, both to avoid teen rebellions, and to try to create an unbiased experiment). Three weeks later, sitting at our kitchen counter after school, my son asked me: “Mom, is it possible my ADD has gone away?” A week later, his history teacher emailed me about his “turnaround,” wondering if we had changed his medication.

Our whole family was eating this new way. I lost 15 pounds without feeling hungry. About six weeks in, my husband noticed that the symptoms of his 16-year-old autoimmune condition seemed to have all but disappeared.

A series of miracles appeared to have taken place in our family in the space of two months. And all we’d done was change what we were eating. I was delighted, relieved—and fascinated. So much so that I took a sabbatical from my corporate job and went right down the rabbit hole, researching metabolic function, disease, its relationship to other health conditions, and how it is affected by diet. I spent a year reading hundreds of scientific studies, attending medical conferences, and interviewing dozens of doctors treating hundreds of thousands of patients with a myriad of chronic diseases, all apparently driven by poor metabolic health.

A National Metabolic Emergency

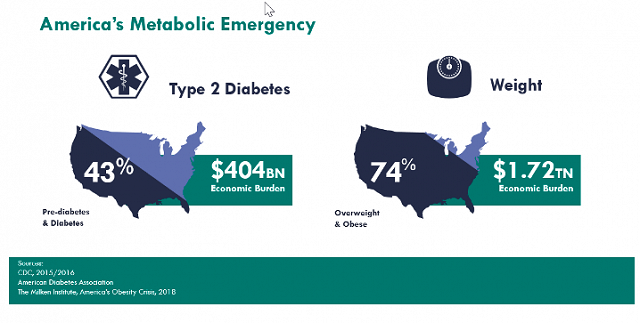

Along the way, I learned that our whole country is in a state of emergency: a metabolic emergency. Three in four Americans are overweight or obese; 60% have a chronic disease; and 43% have pre-diabetes or diabetes. Only 12% of American adults are in good metabolic health, according to a 2018 study by the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Public Health, which concluded that “metabolic health in American adults is alarmingly low, even in normal weight individuals.”

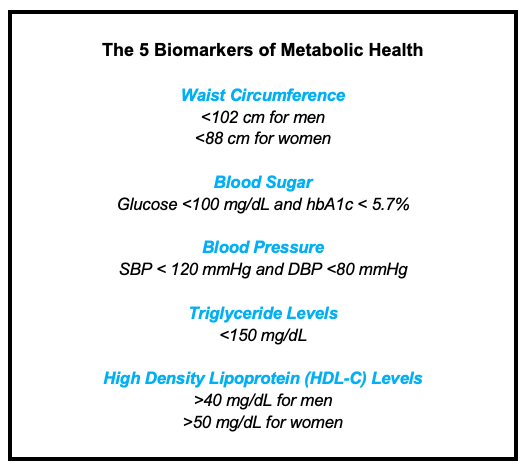

Metabolism is the process of converting food to energy on a cellular level. Metabolic health is signaled by five main biomarkers:

Abnormal results in any one of these biomarkers indicates some metabolic dysfunction; three or more signals Metabolic Syndrome, which means significantly increased risks for many chronic diseases, including obesity, heart disease, stroke, Type 2 Diabetes, kidney disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), Alzheimer’s, sleep apnea, PCOS, and some forms of cancer.

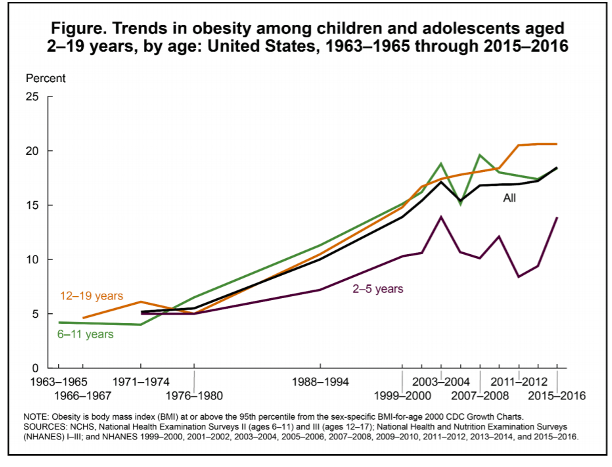

These conditions were once considered “diseases of aging” or “diseases of affluence”. Now we know they are diseases of poor diet—and they increasingly afflict children. Childhood obesity and diabetes rates show damage to metabolic function decades earlier in life than ever seen in human history. These children face high risk of many chronic and infectious diseases over their lifetime.

Bad Advice, Including From the Government

Parents who want their children to lead long, healthy lives do not have many allies. The food and beverage industries pour billions of marketing and R&D dollars into capturing our children as lifetime customers. The general media and policy narrative that treats weight gain and progressive metabolic disease as a simple calorie problem is both wrong and unhelpful. Reducing complex hormonal and metabolic processes to “overeating” has led to unfair blaming and shaming of those who struggle with these conditions, including children and their parents.

Government nutrition guidelines make the situation worse. These are designed specifically only for healthy people, and so do not apply to the 88% of people with impaired metabolic function, or the 60% with a chronic disease, yet they are promoted as the gold standard for every American. The Guidelines have also fallen fatally behind the science on dietary fats and carbs—making their recommendations actively dangerous, given the current state of America’s metabolic health.

Harvard School of Public Health professor David S. Ludwig believes that the Standard American Diet (SAD, aptly named) actually makes maintaining a healthy weight virtually impossible, since it works against our basic biology.

Consuming processed carbohydrates (especially refined grains, potato products, and sugars), causes our bodies to produce more insulin” he writes. “Too much insulin, one of our most powerful hormones, forces our fat cells into calorie-storage overdrive. These rapidly growing fat cells then hoard too many calories, leaving too few available for the rest of the body. So we get hungry.

The price of a “healthy weight”, then, is to live with hunger. Sound familiar? But it turns out this is all wrong. A low-carb diet can maintain, and restore, healthy metabolic function and weight without hunger. In Part 2 next week, I will explain how to make the transition to a healthy (low) carb way of eating easier and more sustainable for your family.

Erica Hauver is the founder of Cook Keto, a Public Benefit Corporation.