Highlights

Across the globe, and especially in the developed world and the United States, fertility rates have fallen below the levels that women say they want. I’ve made this point many times, and in many ways, and have argued that this is a bad sign for society: a world where people systematically fail to experience the family life they desire is likely to be a less happy world.

But one response has been quite common: is there actually any evidence that “missing kids” make parents unhappy? That is, might it be the case that a gap between ideal and achieved childbearing is actually fine because peoples’ abstract ideals aren’t always what would make them happy in the real world?

Women With a “Fertility Gap” Are Less Happy

This is a difficult question to test because it involves a set of basically impossible-to-analyze counterfactuals. We have poor enough data about happiness and fertility preferences to begin with; trying to add in some kind of quasi-causal test of exogenous shocks to the fertility gap would be next to impossible.

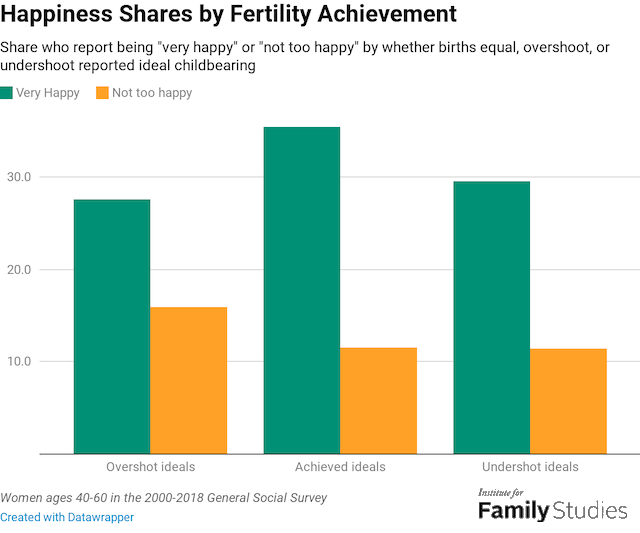

But we can at least look at some basic associations. Some people achieve their fertility ideals, and other people don’t. If the people who do achieve their ideals are less happy than people who undershoot their ideals, then it would be a significant argument against using fertility ideals as a valid measure. So, what actually happens in reality? Among women old enough to have completed their childbearing (ages 40 to 60 in my sample), does the relationship between actual and ideal childbearing predict happiness?

Women whose ideal fertility matches their achieved fertility are the most likely to report being very happy, and the least likely to report being not too happy. Both having more kids than desired and having fewer kids than desired are associated with a lower likelihood of being very happy; having more kids than desired is associated with considerably more unhappiness as well.

In other words, having more kids than she considers “ideal” is associated with a woman being less happy later in life. But it is also the case that not having the number of kids she considers ideal is associated with a woman being less happy! The effect is more modest, of course, but it is nonetheless present.

Recent research has shown that while parents of young children used to be less happy than other people, nowadays that gap has vanished. And while some critics have suggested that these findings are due to poor controls for the composition of childless households, the actual explanation is far simpler. Research on a massive database of developed-country survey respondents shows that children are indeed associated with significantly higher happiness throughout a parent’s life, once you control for financial difficulties. Moreover, if the sample is restricted to a parent’s own children in households where the parents of that child remain together, the happiness effects are particularly large and durable. In other words: if you and your spouse stick together and have babies, and if you are able to avoid financial distress, those kids do indeed make people a lot happier. Those are big “ifs,” but they point to the fact that it is not kids that makes people unhappy, it’s the cost of kids.

This helps explain why women who overshoot their fertility ideals are more unhappy than women who undershoot. It’s not that those moms dislike their above-ideals children! It’s that children are associated with greater financial distress, and financial distress causes unhappiness. If we could help reduce child-associated financial distress, such as through a child allowance, the happiness gap between above- and below-ideals for women would likely even out somewhat.

Fertility Ideals Are Stable

Sophisticated critics, however, won’t be convinced by my chart showing the association between happiness and the fertility gap. They might claim that late-in-life fertility ideals are endogenously determined by happiness: perhaps people who are generally happier will tend to say that their actual childbearing matches their ideals, meaning that the fertility gap doesn’t drive happiness, but rather happiness could drive the measurement of the fertility gap.

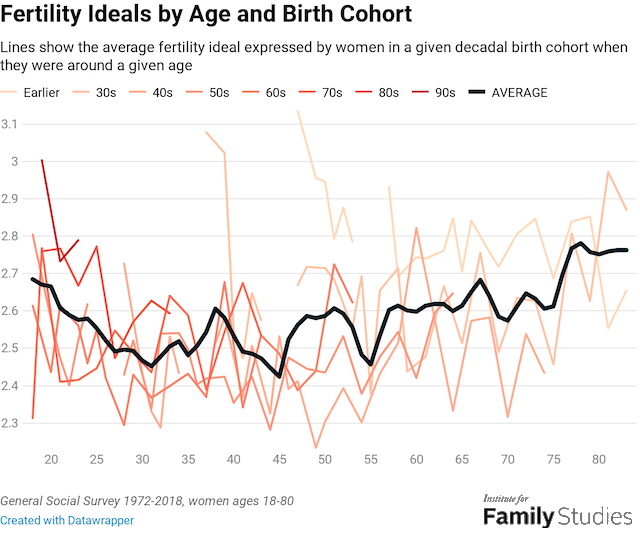

I can’t perfectly rule this out. But there’s at least some good reason to think this criticism is unfounded: fertility ideals are pretty stable across a person’s lifespan. While I can’t link data from the General Social Survey (GSS) longitudinally, I can at least take generational cohorts and see how their fertility ideals have changed across time, which may be a decent approximation of a person’s longitudinal experience.

As you can see, fertility ideals are quite stable over a generation’s lifespan. There’s some variation here and there, and it does seem like fertility ideals may be systematically higher among women under age 20 or over age 60, but for most working-age women, fertility ideals are insensitive to age and birth cohort. In other words, it does not seem like women make large revisions to their fertility ideals around age 40 to 60, the window I use for my analysis of completed fertility. It is possible that individual longitudinal histories would look different, but this chart is at least suggestive that the burden of proof lies on the critics to show that women revise their fertility ideals to rationalize births late in life. It seems far more likely that most women have stable ideals across their lifespan. This may be a contrast to fertility intentions, which research suggests can be quite volatile.

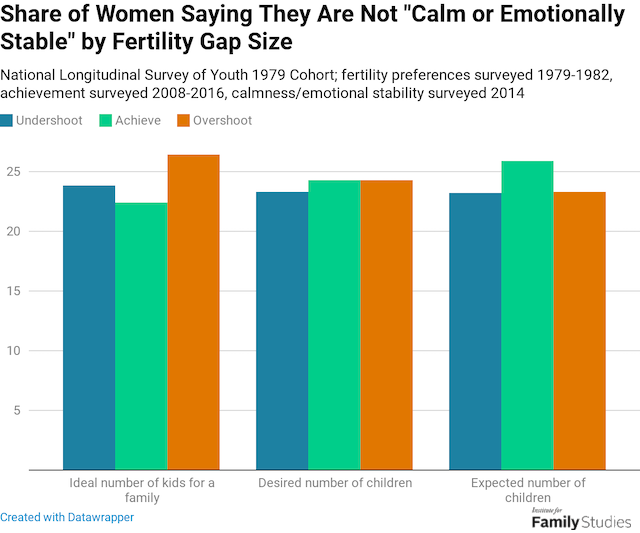

We can also look at the question a different way using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth’s 1979 (NLSY79) cohort. The women in this survey were asked in 1979 and 1982 about their general fertility ideals, their personal fertility desires, and their personal fertility expectations. Later in life, when these women were in their 50s, they were also asked a series of personality questions, one of which asked them whether they felt they were “calm or emotionally stable.” This is the closest I could find to a question about happiness or life satisfaction in the NLSY79. Looking at the women who said they were not “emotionally stable” is informative.

Women who had the number of children they had said was ideal for a family in a survey 30 years earlier in their life were slightly more likely to say they were emotionally stable than women who over- or under-shot their ideal fertility. Again, overshooting looks riskier than undershooting: although if we restrict it to just women who strongly agreed that they were emotionally stable, overshooting looks better than undershooting.

When it comes to personal desires, we see that undershooting is associated with slightly lower rates of emotional instability, but the difference is small and it vanishes if we restrict to women with the strongest expressed sentiments. Looking at expectations, we can see that women who achieved their childbearing expectations say they are less emotionally stable; but this may be because women with higher childbearing expectations were more likely to have already had a child when they were surveyed in 1979 or 1982, and teen pregnancy can have negative effects on a woman’s life outcomes.

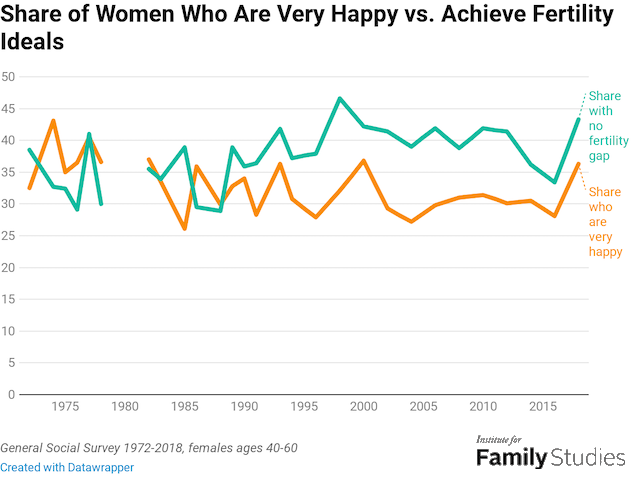

In other words, the achievement of general fertility ideals actually does seem to be associated with at least one indirect measure of happiness even using longitudinal data. Finally, it turns out that the fertility gap as measured by the GSS explains a large share of the variation over time in happiness among women ages 40 to 60. The chart below compares the share of women in that age bracket whose achieved fertility equals their ideal fertility, as well as the share of women ages 40 to 60 who report being “very happy.”

Again, this is a very simple association, and so isn’t conclusive proof that the fertility gap causes unhappiness. But it certainly suggests that when analyzing the relationship between children and parental happiness, it may be important to think about parental fertility preferences. An additional child may be associated with very different happiness effects if it is helping a family achieve their desired number of kids, versus if it’s pushing them past their desired number of kids, and possibly into financial distress.

Thus, it doesn’t seem like what’s happening is just a matter of women redefining their current circumstances as ideal. It seems like what is happening is that there are real costs, in terms of happiness, to women not achieving their desired fertility. The fertility gap is associated with meaningful differences in happiness in cross-sectional data, fertility ideals don’t seem to change a large amount over a generation’s lifespan, and the prevalence of fertility achievement seems related to changes in happiness.

It turns out that if you read the surveys and listen to women, they aren’t just making things up when they express their fertility ideals. These stated preferences are meaningful and represent real differences in happiness when not achieved.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.