Highlights

- The shock that the coronavirus has delivered to the structures of work and parenting could contribute to increases in fertility from below replacement in the long run. Post This

- COVID-19 has accomplished what public policy could not, namely widespread recognition of the needs of working parents and use of technology to keep workers productive when they are not in the office. Post This

To date, two threads of coronavirus speculations are not speaking to each other yet: questions surrounding 1) what the pandemic will do to fertility levels going forward, e.g., here and 2) what the pandemic will do to gender equity, e.g., here. The connection jumps out for me because I’ve just finished drafting a research paper that confirms that widespread gender equity continues to be associated1 with higher fertility levels in Europe and North America.

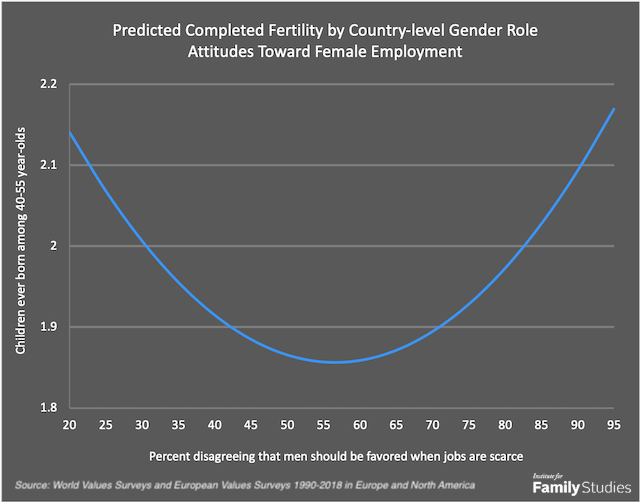

The pre-coronavirus world was one characterized by an incomplete gender revolution, and I fully expect the newly unfolding world to be the same. But could this shock to our lives disrupt traditional gender roles enough to move us toward the fertility recovery shown to the right in the graph below?

Note: Predicted fertilty calculated by controlling for individuals' age, education, and gender role attitude;

the country's percent attending religious services regularly, percent gender equitable (and its square),

and the data source (survey and year).

First, take a look at the left side of the graph: that’s the story of the first half of the gender revolution weakening the family. When women move into the paid labor force, they tend to have fewer children. The horizontal axis measures the share of individuals who disagree that men should be favored when jobs are scarce, i.e., the share supporting workplace equality. This is a values measure, and as egalitarian gender role attitudes become more common, fertility goes down.

But only at first. After the share valuing workplace equality reaches about 60%, further increases in country-level gender equity are associated with fertility recovery. I’ve come to understand the right side of the graph as the second half of the gender revolution strengthening the family. A Reader’s Digest version of this explanation runs something like this: initially, workplace equality was synonymous with a second shift for women, and they didn’t bear as many children because they still provided the lion’s share of domestic labor while also working paid jobs; but, as women’s work becomes more normative, both societies and men adapt to support the needs of working mothers (societies develop family-friendly policies; men contribute more in the private sphere as they are encouraged to do so by a spreading egalitarian ethos, norms for intensive parenting, and the raw practical need for domestic labor).

Which brings us to the pandemic. Work has become more flexible in many (certainly not all) occupations. COVID-19 has accomplished what public policy had not, namely widespread recognition of the needs of working parents and use of technology to keep workers productive when they are not in the office eight hours a day. Think of it as a shock to both childcare and work and, as such, a shock to the gender system.

You can envision this shock in a couple of ways. One is focused on how people’s values might change when work/family conflict becomes up close and personal. This perspective was highlighted in a CNN Business article that explained how husbands finally understood how much it took to keep a home running, either because they are home to see all the work, or they have to fly solo for the first time on the home front because they are married to health care or other essential workers (78% of health care workers are female). Increased empathy for the demands of the second shift can lead men toward more egalitarian behavior, and egalitarian norms can follow—pushing nations to the higher fertility levels at the right of the graph. In other words, if the family was weakened by female labor being diverted from the domestic sphere into paid work, it can be strengthened by men contributing more in the domestic sphere. Further, it isn’t just empathy that matters: evidence from paternity leave policy indicates that short leaves are associated with greater involvement with childcare in the long run. That means a nasty virus might spur better father-child relationships that, in turn, leave mothers not quite as stretched.

A second way of picturing how the coronavirus might contribute to fertility recovery is to imagine the whole graph shifted to the right. The historical evidence indicates that when more than 60% are gender equitable, there is potential for fertility recovery. The period from 1990-2018 depicted above is starting to seem like ancient history. Even if individual men don’t lean in on the home front, would it really take 60% supporting gender equity to see the kinds of workplace changes that make combining work and childrearing easier? I think not. Family policies, like childcare subsidies, which are more common in social democracies, might be a sufficient, but not necessary, condition for fertility recovery. Couples might be more likely to believe they can actually manage having more than one child as a result of workplaces becoming more flexible.

The structure of work is undoubtedly changing. As a result of the pandemic, my home state of Maryland obtained federal funding to expand an innovative but previously small workshare program. Businesses, too, are rapidly adopting flexible work arrangements (see a summary here), even in countries like Italy that used to be particularly resistant to telework.

In short, I think that the shock that the coronavirus has delivered to the structure of work and the structure of parenting could contribute to increases in fertility from below replacement in the long run. The long-run argument is a long way away from debates about whether fertility will be boosted—by babies conceived in quarantine or because of disruptions in contraceptive supplies—or whether it will be depressed by uncertainty or disruptions in mating markets.

But will the epidemic actually boost fertility in the long run? In part, it depends on whether men who take on child care responsibilities during the epidemic enjoy doing so. Men could opt out of further childbearing after discovering how hard childrearing really is (see, for example, how Spanish men taking paternity leave responded here). Opt-out is particularly likely if parents come to believe they can’t count onpublic schooling for during-the-day childcare. It is also possible that a shock isn’t enough to disrupt cultural norms that view fathers as ancillary parents and mothers as somehow lesser employees. The outcome, then, would be that all this workplace flexibility lengthens the second shift more for women than for men, and any fertility recovery from reconciling work and family demands could be crushed by the weight of the demands.

And finally, the magnitude of the fertility response will hinge on what share of people’s fertility behavior depends upon a favorable context for preference implementation, a hotly debated topic (see here vs. here). The potential for the pandemic to contribute to fertility recovery in the long run is there, but it is hardly certain.

Laurie DeRose is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Catholic University of America, and Director of Research for the World Family Map Project.

1. The association had been established with older data; I simply incorporated the most recent wave of the European Values Survey.