Highlights

In my work as an anthropologist, I’ve become convinced that American lifestyles are increasingly diverging between “hyper-achievers” trained early on to succeed, and those often labeled “slackers” whose lives revolve around entertainments of various sorts. You won’t be surprised to learn that a disproportionate percentage of “slackers” are men. Males, particularly in the working class, are working less, earning less, and are increasingly disconnected from families and from society as a whole. The future prospects for many working-class men seem very dim.

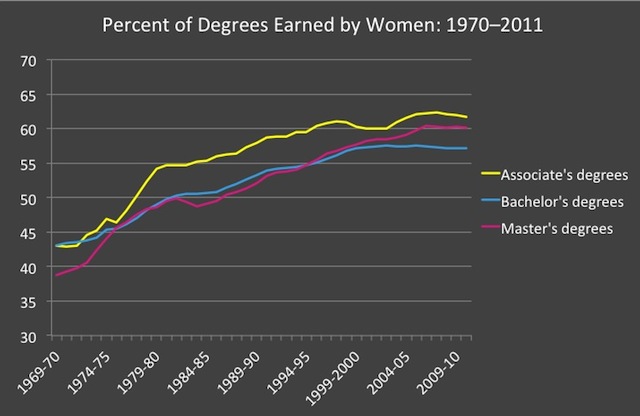

In analyzing these trends, many point to the effects of economic restructuring, with its loss of well-paying working-class jobs that resulted in a bifurcation of high-paying jobs for the educated and low-paying jobs for the uneducated. But men are struggling even when well-paying working-class jobs are available, and many have problems just graduating from high school or getting needed technical training. Early on, they fall behind females in school, and they never catch up: women earn a growing majority of college and graduate degrees, as the below chart shows. Some colleges even resort to a type of male affirmative action in order to keep gender proportionality somewhat equal. Women are getting more education, whereas men are not, at a time when it is economically imperative. What is going on?

Source: National Center for Education Statistics

Dr. Leonard Sax’s Boys Adrift lists video games among the causes of boys’ school struggles, not because they drive boys to violence, but because they create a need for stimulation, crowd out reading, and lessen boys’ focus in school and other activities. (Boys play console games, commonly used for sports and violent games, at four times the rate of girls.) Rates of ADHD have skyrocketed, and the causes of this are unclear, but overstimulation may play a role. These patterns can also lead later in life to heavy television viewing, often of sports (witness the domination ESPN has over the male gaze), and heavy online activity, such as viewing porn.

After we go to school, we need to look at family. One explanation for poor and working-class men’s instability points to the fact that so many were raised with single parents, as economists David Autor and Melanie Wasserman report. This has created a vicious cycle contributing to generational poverty, since education lags in these homes and children often fall behind their peers from two-parent families. With low rates of marriage and high rates of divorce among less-educated Americans, men raised by single parents are unlikely to reap the gains of a lasting marriage themselves. “What happens to a lot of guys who become unmoored from family life, they become unmoored from everything…they are just living without attachments and by the time they are 40 or 50 years old, the things that kept these men from falling away—family and community life—are gone,” according to Kathryn Edin.

Unstable family dynamics lead individuals to seek groups where they can fit in.

These unstable family dynamics lead individuals to seek connections and groups where they can fit in, and contemporary society offers a plethora of subcultures that supply this need. In the inner city, gangs are often a family substitute, a way to connect with other males. White working-class males are prone to take on a “southern rebel identity” that rejects middle-class roles and education, career and family. This particular form of masculinity opposes authority, promotes drinking and using drugs, and can be misogynistic, as ethnographer Jason Eastman describes.

The origins of various subgroups can sometimes be found in high school cliques, such as “cowboys,” “skaters,” “burnouts,” “stoners,” or others. They are tied together by common activities, music or other symbols and forms of popular culture. Men also tend to be attracted to more risk-taking activities, whether in leisure or crime, which sociologist Stephen Lyng describes as “edgework.” Once men get criminal records, as many in gangs and other marginal groups do, it’s much harder for them to obtain jobs—which reinforces their place on the edge of society.

All of these things mentioned above—early reliance on stimulating entertainment, lower educational attainment, disconnection from families and role models, and the attractions of different, “edgy” subcultures—contribute to a widening gulf between those more connected to family, work, and society, and those without these commitments. While men are losing connections, women continue to participate in the labor force, attend religious services more often, and belong to other community and civic organizations. This is partly because many have dependent children and need to support them, whereas men can to a large extent avoid this responsibility.

Men who are not committed to families enjoy all the options that a consumer culture gives them, have more independence and freedom, and thus are found in a wider array of subcultural activities that take men away from consistent work and commitment to families. At the same time that non–college-educated men have fewer economic opportunities, they have more opportunities to indulge in various consumerist activities. That’s a recipe for ever-widening gaps between these men and the rest of society.

Michael Jindra is a visiting research scholar in the Center for the Study of Religion and Society and an adjunct associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Notre Dame. He has published in both sociology and anthropology, and is currently writing on the tensions between diversity and equality and conducting research on antipoverty nonprofits.