Highlights

- One question in the Harris poll spotlighted the concern that people shouldn’t have children because the potential child’s quality of life would be too poor. Post This

- Evidence suggests that the decline in parenthood isn’t explained by rising out-of-pocket costs, such as food, diapers, or housing, so much as the opportunity cost of parenthood. Post This

- Untangling the mix of economic pressures and cultural change driving lower fertility requires a more careful analysis than the impression this new Harris poll might give. Post This

One of the most important questions facing our society right now is whether declining rates of marriage and fertility are the result of changing preferences or of economic pressures. The “two-income trap,” housing and child care costs, and student loan debt have all been blamed for people delaying or forgoing getting married or having children.

But as I recapped for the IFS blog last February, some of the better research out there suggests that when it comes to declining fertility, it’s not simply “the economy, stupid.” Certainly some, perhaps even many, couples may be dissuaded from forming a family by the high cost of living. But the evidence suggests that the decline in parenthood isn’t explained by rising out-of-pocket costs, such as food, diapers, or housing, so much as the opportunity cost of parenthood. What would-be parents have to give up, in the form of forgone job opportunities or educational attainment, seems less appealing than what they’d get with a ring and a baby carriage.

This story leaves some unsatisfied. Populists on the left and right would like the culprit behind low birth rates to be the ravages of late-stage capitalism or the rapacious globalist elite who want us to “own nothing and be happy.” But the balance of available research, summarized best by a paper last year in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, suggests the larger culprit behind declining marriage and fertility is not economic in nature, but better described by the amorphous bucket of “cultural change.”

Of course, cultural attitudes can themselves be influenced by economic changes. Having a child might mean forgoing graduate school or passing up that big-time promotion. And the cultural expectations around parenthood—strollers that cost in the four digits, enrichment activities and the like—raise the ante to being considered a “good” parent.

A new survey from Harris Interactive and the Archbridge Institute tries to shed light on what might be driving lower fertility. In an op-ed tied to the release of the study, the Archbridge Institute’s Clay Routledge and Harris CEO Will Johnson said their findings provide evidence that the predominant reason cited by Americans who do not want kids is a desire to maintain their personal independence, rather than economic pressures or environmental concerns.

Among adults of all ages, there was a notable gender split in the survey: 63% of women without children said they had no desire to have a child, while only half of males said the same. (A smaller gender gap appeared when it came to marriage: 46% of men wished to wed, while only 40% of women said they wanted to get married.)

At first glance, the survey results seem to provide strong evidence that shifting cultural preferences are a bigger driver of declining fertility than financial constraints. For men, the most commonly-cited factor (33%) was personal finances, but among women, 42% said the strongest consideration influencing their decision not to have a child was their desire to “maintain their personal independence.”

However, there is a major limitation in these topline results—they include all adults who told pollsters they didn’t have children and weren’t planning on having children, including members of the so-called “Silent Generation” and Baby Boomers. The Harris crosstabs show that two-thirds of the sub-group that replied they didn’t have children or want children in the future were ages 42 or over (208 out of 317 respondents). This makes the study much less useful for understanding how people currently contemplating having a child might be weighing the tradeoffs.

A focus on responses by adults in their prime reproductive years suggests a different set of concerns. Though before examining them in too much detail, it is worth nothing that they are plagued by small sample sizes; just 65 respondents in this subgroup were ages 25-41 and 32 were ages 18-25 (after all, more than half of Millennials and Gen Z polled said they want to have a child in the future!)

Drawing inferences about the self-reported decision to forgo having a child based on a sample of 32 young people who might not have even graduated college should be done with extreme caution. As the conservative writer Bethany Mandel beautifully illustrated at Common Sense, sometimes teens who say they don’t want kids end up with five and a sixth on the way as adults (and many of us can think of couples who desperately would love to welcome children, but have difficulty conceiving.)

But even taking the results at face value, a weighted average of both Gen Z and Millennial respondents suggests a greater role for economic concerns than the topline results. The crosstabs suggest that for about three in 10 young adults (ages 18-41) who say they do not want to have children, the biggest factor in their decision is their personal financial situation, followed by work/life balance, at 21 percent. “Maintaining my personal independence” came in third, at 18 percent.

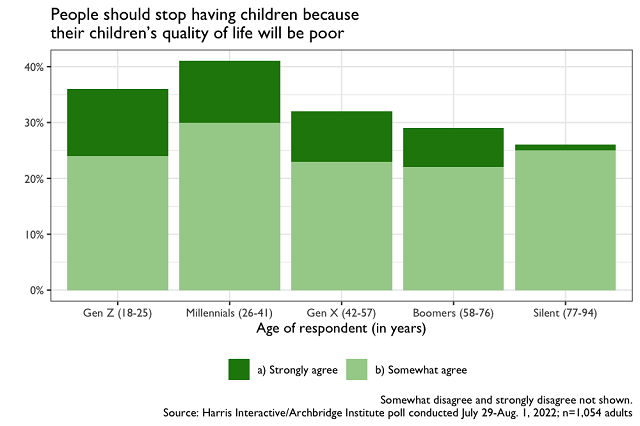

That is not to say some cultural change is not at play as well. Young adults are much more likely to express concern about reproduction and its connection to climate change. One question in particular spotlighted the concern that people shouldn’t have children because the potential child’s quality of life would be too poor.

Note: Author's analysis of Harris Interactive/Archbridge Institute poll, October 2022

Millennials (four out of 10 of them!) seem especially guilty of this misguided sense of compassion for the unborn. These concerns may be well-meaning. But the idea that bringing children into the world in a 21stcentury-level quality of life would be somehow ill-advised compared to other periods of world history requires some unpacking, to put it mildly.

There is no question that cultural attitudes are changing. A recent IFS post by Alysse El-Hage reviews a new tranche of data on high school students: 71% of teens in 2020 said they expected to marry, down from 81% just 15 years prior. Moreover, an excellent new IFS and Wheatley Institute report by Lyman Stone and Spencer James reminds us that if you care about low birth rates, you should also care about low marriage rates. And if you care about low marriage rates, you should be pulling on every lever—political, cultural, and personal—to make getting married more attractive, affordable, and achievable.

But untangling the mix of economic pressures and cultural change driving lower fertility requires a more careful analysis than the impression this new Harris poll might give. A retrospective look at why adults who grew up in the 1970s didn’t have children might have tremendous sociological value, but it does little to shed light on the dynamics around childbearing and marriage for those currently considering deferring parenthood, or putting it off altogether. We should interpret the results accordingly.