Highlights

- A combination of religious immigration, immigrant religious retention, a rising prevalence of believers among the affiliated, and higher native religious birth rates will result in a plateauing of secularizing trends by mid-century. Post This

- Despite high marital satisfaction among secular progressive couples, I remain unconvinced that progressive secular fertility will rebound, as Laurie DeRose argued in her IFS post. Post This

In a recent piece I wrote for the London Metro, I agreed to the title “Society will become conservative and sex will go back to procreation rather than recreation.” Laurie DeRose rightly raises important questions about this eventuality in her recent IFS blog piece.

First, it’s important to understand that the Metro is a London commuter paper, not a serious broadsheet newspaper, whose “Future of Everything” series is a fun and provocative look at what may happen down the line—in this case, in the realm of sex. While I agreed to pen this piece as part of the series, I did not get to choose the title.

While I do believe societies will become more religious as committed, especially anti-modern, religious sects demographically increase, I made no claims in the article about whether sex would be more or less satisfying to participants in the future. So, I endorse DeRose’s comments on this.

But my broader argument about the rise of committed religious groups remains. In my book, Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth (2010), and in academic articles on Europe and the US with demographers Vegard Skirbekk and Anne Goujon, I argued that the dominant trend in Catholic Europe and the United States is secularization.

Robert Putnam, whom I met in 2008, showed me data which confirmed numbers I had seen from other sources indicating that American under-25-year-olds were 35-40% unaffiliated. At the time, and in American Grace (2010), Putnam and his co-author David Campbell argued that the decline in religiosity was a period effect caused by young and liberal people being turned off faith by the Christian Right. I put it to Putnam that the numbers looked more like a European-style secularization trend. I still hold to that view.

The decline in religiosity, as Charles Murray shows, was especially pronounced among the white working-class. This group has had both the steepest increase in non-religiosity and the sharpest falloff in weekly worship attendance.

Given all this, how can it be that projections I undertook with Skirbekk and Goujon show a leveling off in the meteoric rise of American non-religiosity by 2050?

One answer lies with immigration. Few American immigrants arrive from wealthier secular countries because 97% of the world’s population growth comes from the 95%-religious global South. Meanwhile, immigrants comprise a historically high and rising share of the U.S. population. Even within Latin America, relatively secular Chile and Uruguay supply far fewer immigrants than highly religious Honduras and Guatemala.

While there isn’t American census data on religion to allow us to disaggregate to the urban level, we can use a British analogy. In the 2000s, the number of religious people fell by over 2 million across England and Wales, and the Christian-identifying share slipped from 71 to 59% of the population. Yet, the number of religious people in London—a highly diverse city which is only 45% White British—rose by 440,000 in a decade as 1.6 million non-White British settled in the city. In seven London boroughs, secularization went into reverse. In rapidly diversifying Redbridge and Newham, the non-religious share fell by half. Christianity held up far better in the capital than in rural and provincial areas. Ethnic minorities, including Christians, had a far slower shift to nonreligion between 2001 and 2011 than White Britons.

The second factor to consider is religious Americans’ fertility premium over nonreligious Americans. This has been repeatedly confirmed in studies, and regular church-attenders appear to have about a half-child advantage of those who never attend services. At present, this advantage is overwhelmed by the pace of switching to nonreligion, especially among young people. I would expect this to continue for some time.

Yet the rule in demographic projections is that switching and migration matter most in the short run, while fertility differences count most in the long run. In my book, I used the analogy of a treadmill, in which the speed of the treadmill is secularization and the incline is religious fertility. Right now, the speed of switching to nonreligion is sufficient to overwhelm the incline. But because of its demographic disadvantage, secularism must run to stand still.

Now that nonreligion, or even atheism, is more acceptable in America, social pressures against non-belief and non-attendance are relaxing. Thus, the actively religious will shrink to a core of true believers rather than those who belong without believing. As this process continues, it may become more difficult to recruit new switchers as the rump becomes increasingly composed of believers rather than social belongers.

We arguably see this in the “mature” secular societies of Europe, notably Scandinavia and France, where nonreligion seems to have leveled off at around half the population, with about 5% weekly attenders. Secularization has effectively halted or may even be slipping.

The U.S., in my estimation, will achieve a steady state above this level. One reason is because mainline denominations—a functional equivalent of Europe’s established churches—are hollowing out toward both fundamentalism and secularism. Evangelicals are not declining as fast as mainline denominations.

Meanwhile, anti-modern fundamentalist sects and cults such as the Amish, Hutterites, ultra-Orthodox Jews and, to some degree, Mormons, have immense growth potential due to a combination of high fertility and high retention. The latter stems from the fact that leaving one of these religions is considerably more difficult than failing to show on Sunday at the local Episcopal church. It typically means turning one’s back on friends, family, and identity.

The largest of these demographically-powered sects are the Mormons. Though numbering 6 million, they are also the least cohesive, with less of a fertility advantage over other Americans. In 2015, according to Pew, the completed TFR of Mormons was 3.4, compared to the U.S. average of 2.1. Still, if maintained over generations, this can produce dramatic aggregate-level shifts in religious composition.

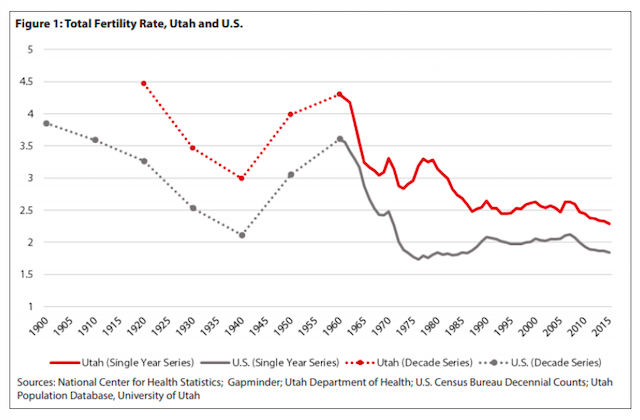

Has the economic crisis of 2007-8, which depressed fertility across the western world, hit the LDS church harder? This is the argument of Lyman Stone, who uses CDC data to show that, in 2015-16, fertility fell faster in Mormon-majority Utah than almost anywhere. However, as Conrad Hackett at Pew suggests (see figure 1), the CDC data seem to show that Utah is merely following the national pattern.

In which case, the long history of Mormonism’s steady fertility advantage seems set to continue. Absent good data on switching behavior in Utah and Idaho, it would likewise be premature to argue for significant LDS secularization. I would, therefore, assume a continued increase in Mormon share in its Utah-Idaho core.

Despite high marital satisfaction among secular progressive couples, I remain unconvinced that progressive secular fertility will rebound, as Laurie DeRose argued in her IFS post—at present, there is little data to support this claim.

Overall, the picture suggests that the U.S. will continue to secularize in the coming decades. However, a combination of religious immigration, immigrant religious retention, slowing religious decline due to a rising prevalence of believers among the affiliated, and higher native religious birth rates will result in a plateauing of secularizing trends by mid-century.

Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London, and author of Whiteshift: Immigration, Populism and the Future of White Majorities (Penguin/Abrams, 2019) and Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth: demography and politics in the twenty-first century (Profile 2010).