Highlights

Writing in the Metro, University of London professor Eric Kaufmann recently argued that in the foreseeable future, sex will go back to “procreation rather than recreation.” This prediction seems hard to fathom in today’s culture that values individualism as an intrinsic good and that seems wary of irreversible commitments. But his prediction is founded on the rather simple premise that religious populations are growing, while more secular ones are shrinking.

This “demography is destiny” argument follows naturally from the fact that fertility dominates both mortality and migration in determining group size. It goes something like this:

- People with strong religious identities have more children than their counterparts, whether secular or nominally religious.

- Death rates don’t matter much for the relative size of groups since everybody dies once; birth rates are paramount because they vary much more. Put differently, a person can contribute much more to population growth by having children multiple times than by staying alive longer.

- Conversion is like migration in that it has the potential to affect group size, but in practice, birth rates still dominate. To understand this point, think about sub-Saharan Africa, the fastest growing region on the globe: massive emigration hardly slows population growth because there are far more people being born than moving out. Children born into religious families do convert to secularism, but not enough to overcome the fact that there are so many of them.

Kaufmann added that the reason the composition of future populations will be defined by religion is that modernization has driven down birth rates everywhere, but highly-religious groups living in the most modern environments have actively rejected small families. Even fertility that would have been moderate in a by-gone age—say a family with four children—matters a lot for the religious composition of future populations when secular women are much more likely to have one child than four. Kaufmann drives home the plausibility of his argument using the example of Jerusalem that “has flipped from secularism to conservative religiosity” due to the Orthodox having much larger families than more liberal Jews. He projects that the rest of Israel will follow suit in the relative short run, while it will take longer in places like the United States—until the 2100s.

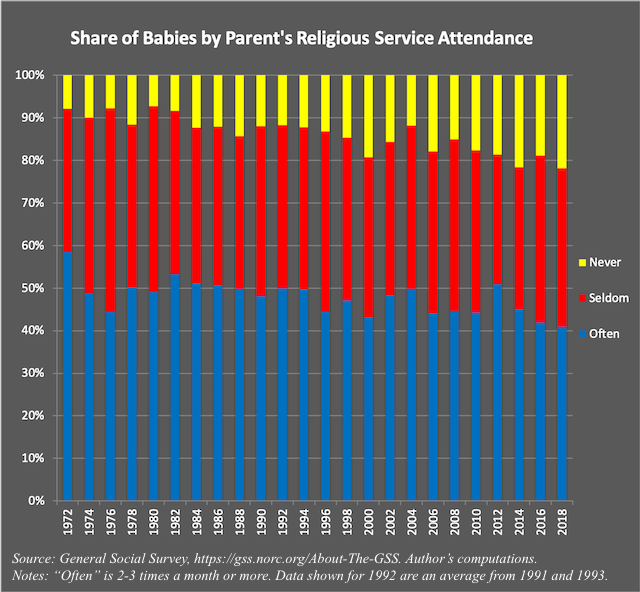

All of this is mathematically reasonable, and Pew also projects that the share of people on the globe unaffiliated with any religion is expected to fall from about 16% now to about 13% by 2060. There is no evidence, however, that “sacralization by stealth” has begun in the United States. Here’s what the General Social Survey reveals about the religious composition of parents over time:

The data span 46 years, and the share of babies born to those who never attend religious services has increased, rather than decreased. It is, of course, possible that in the future, the proportion of babies born to religious parents will increase.

Nevertheless, there are at least two fundamental reasons that I think Kaufmann’s prediction about sex becoming more about procreation rather than recreation is wrong. First, he underestimates the potential for “fertility rebound” among secular couples. Second, he makes faulty assumptions about the relationship between religiosity and fun in bed.

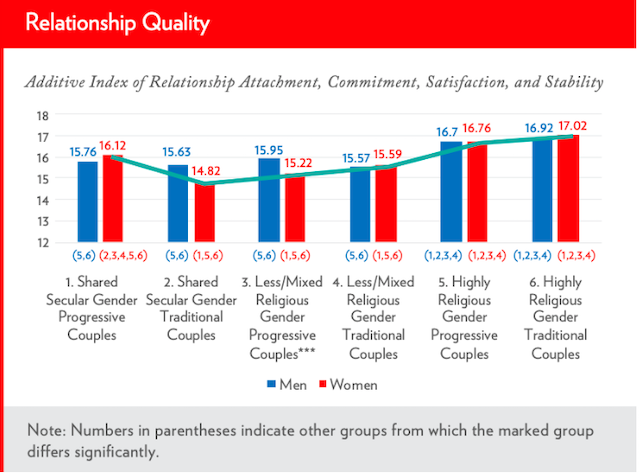

Starting with the less sexy of my two objections: gender egalitarianism can contribute to childbearing. The assumption that secularism will continue to predict the lowest fertility rates as it does now doesn’t incorporate scholarship showing that both egalitarian societies and men’s involvement with childrearing increase fertility. There is no equivalence between “egalitarian” and “secular” (nor between “gender traditional” and “religious”), but a good share of women are in relationships that are both egalitarian and secular—and they report higher quality relationships than all but their most religious counterparts, as we found in our recent report, The Ties That Bind.

Source: World Family Map: The Ties That Bind, 2019.

Relationship quality matters tremendously because today’s below-replacement fertility doesn’t result from low-fertility desires as much as from people who want children not having them. Happier people are more likely to achieve their desired fertility rather than to stop short, and women in both gender progressive secular couples (group 1 above) and religious couples (groups 5 and 6 above) are happier than others. The happiness among gender progressive secular women can be expected to translate into higher fertility as more societies adopt policies that take some of the stress off working mothers (such as free universal preschool and tax breaks for families that hire domestic employees).

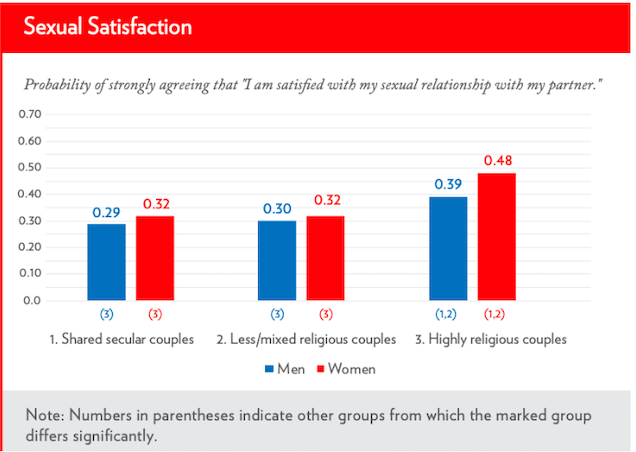

Second, even if highly religious couples didn’t share part of their fertility advantage with secular progressives, Kaufmann makes a mistake by equating “a fundamentalist future” with sex being “about procreation, not recreation.” As someone well-acquainted with Christian teaching about the joy of marital sex, I was happy to discover that myths about religious Puritanism regarding marital sex are being publicly debunked. Further, current social science research supports the idea that religious couples have fun in bed, as we found in our recent report:

Source: World Family Map: The Ties That Bind, 2019.

The skeptical might interpret these data as indicating that religious couples exaggerate their contentment with their relationships, but I suspect that would likely inflate the proportion simply agreeing that they were satisfied with their sexual relationship with their partner, and these data are for strongly agreeing.

In short, Kaufmann’s conclusion stems from treating two things with far more linearity than reality suggests. While I agree with him that fertility differentials favoring the religious will persist, he ignores the possibility that a “fertility rebound” will be pronounced among the secular relative to the nominally religious. The implication is that future populations won’t be as heavily religious as he assumes. Moreover, assuming a linear relationship between sexual freedom and sexual joy ignores that fact that commitment enhances sexual pleasure. In a highly religious population, sex can be about both procreation and recreation. Even today, most secular people use sex for procreation at some point in their lives, and both procreative and recreational functions of sex would likely persist in a future of any religious composition.

Laurie DeRose is a Research Assistant Professor at the Maryland Population Research Center at the University of Maryland at College Park and a senior fellow with the Institute for Family Studies. She is also Director of Research for the World Family Map project.