Highlights

- Married parents tend to be almost twice as happy as single childless Americans. How then do we reconcile this paradox? Post This

- Not only do married parents have less free time than single non-parents do, the free-time gap has grown over the past two decades. Post This

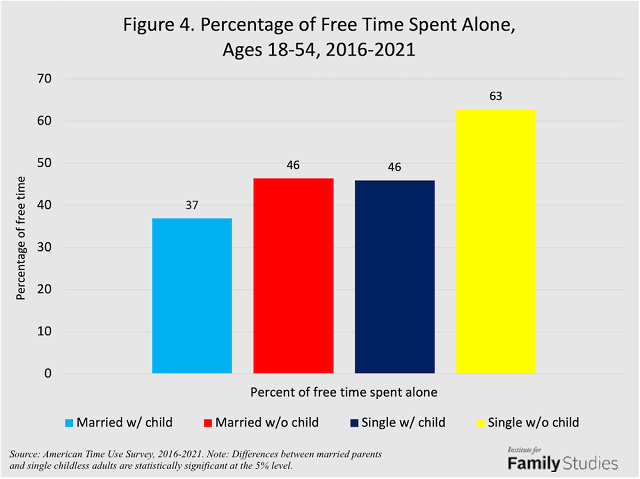

- Single childless people spend 63% of their free time alone. Married parents, on the other hand, spend only 37% of their free time alone. Post This

Many of the strongest opponents of marriage and parenthood argue that singleness and childlessness afford people more freedom to pursue their own interests. In the words of Psychology Today, “single people, especially those who live alone, are the captains of their own ships... people who love being single use their freedom to do what really matters to them.” If it is true that single childless people have more autonomy than married parents and use their free time purposefully, we would expect those without a spouse or children to be relatively happier. But the data tell a different story. Married parents tend to be almost twice as happy as single childless Americans. How then do we reconcile this paradox?

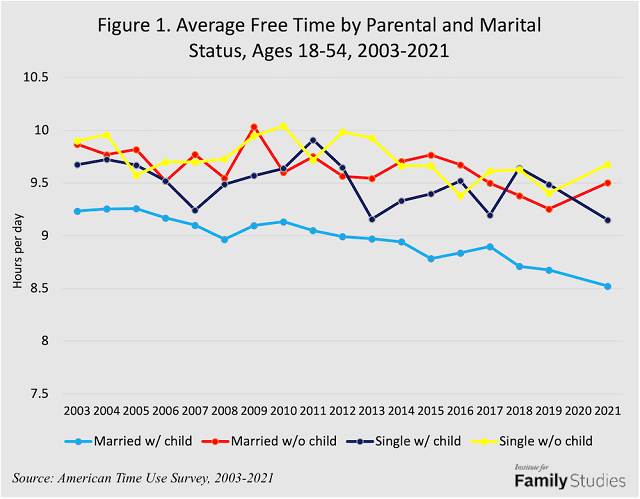

Single childless people certainly have more free time than married parents. Using the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), I calculate the average amount of free time that each parental and marital group has for each year from 2003-2021, and present the results in Figure 1. I define free time as all of the time that a given person is not working or caring for others, excluding personal care time (which counts time spent sleeping, bathing, and the like).

Not only do married parents have less free time than single non-parents do, the free-time gap has grown over the past two decades. In 2003, single people without children had about 10 hours of free time per day, compared to 9 hours and 15 minutes for married parents. By 2021, the gap between married parents and single childless adults had grown to over an hour (9 hours and 40 minutes for single childless people compared to 8 hours and 30 minutes for married parents). Note also that married parents spent an average of over 90 minutes per day caring for others, versus only 7 minutes per days for single and childless adults.

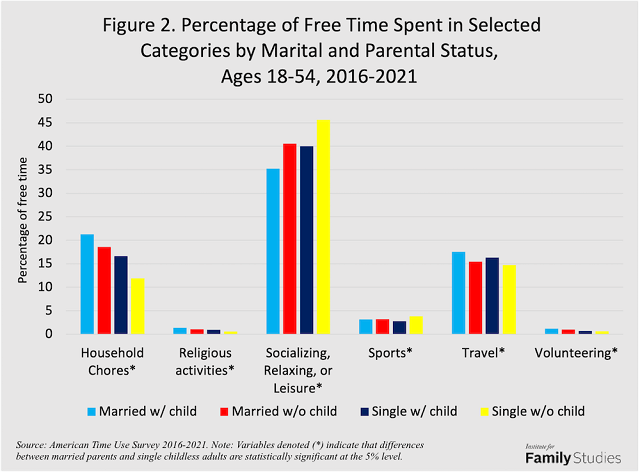

But “free time,” as defined above, does not tell the whole story. Single childless people may spend less time working and caring for others, but that does not tell us how they spend their free time. Thankfully, the ATUS allows us to answer that question. The ATUS breaks down every respondents’ time use into several “major categories,” grouping together a set of specific activities that are generally similar. There are 13 major categories not including working, caring for others, or personal care. I calculate the percentage of each groups’ free time spent in each major category on a daily basis, and present six common categories in Figure 2.

Compared to single childless adults, married parents spend slightly more time in religious activities, volunteering, and traveling, and slightly less time exercising or playing sports (all of these differences are significant at the 5% level). But because these activities only occupy a small portion of each groups’ free time, these differences are largely negligible. The most significant differences between married parents and single childless adults is in how much of their free time is dedicated to household chores and socializing. Married parents spend over 20% of their free time doing work around the house, compared to only 12% for single childless adults. Moreover, single childless people spend over 45% of their free time socializing, relaxing, or in leisure activities; married parents spend only 35% of their free time socializing or relaxing.

So, we see that single childless people spend far more time socializing and relaxing and far less time doing household chores. Why, then, are they less happy? The ATUS allows us to take an even closer look into what specific activities each group does on a daily basis, and with whom they are doing each activity.

We know, for example, that certain activities can either enhance or diminish one's well-being, and being in the company of others might be more beneficial than staying in isolation. These variations could potentially offer insights into why there is a difference in happiness levels between married and single individuals.

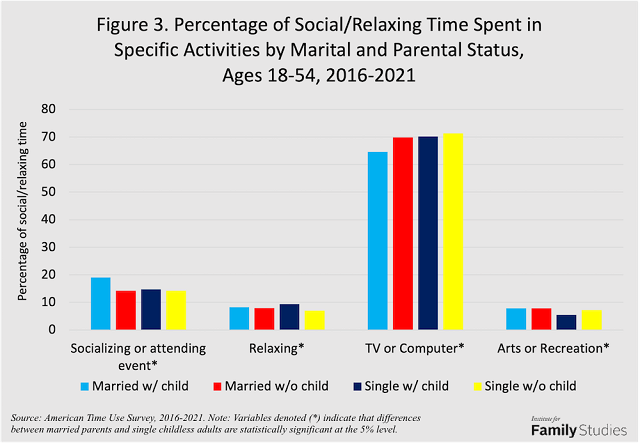

The “socializing, relaxing, and leisure” category in the ATUS groups together a wide array of specific activities—ranging from spending quality time with friends and family to playing video games and watching television. Figure 3 breaks down each groups’ social/relaxing time into four specific activities: socializing or attending social events, relaxing, watching television or spending time on a computer (which also includes time on phones and social media), and time spent attending or engaging in the arts. Figure 3 shows the percentage of each groups’ social/relaxing time in each activity.

As the figure makes clear, each group spends the vast majority of their social/relaxing time in front of a television, computer, or phone screen, and only a small percentage of their social time doing genuinely social activities. But some key differences emerge between married parents and single nonparents. Single nonparents spend over 70% of their social/relaxing time in front of a television or computer screen, compared to 65% for married parents. Where do married parents allocate that extra 5% of their free time? Socializing with others in person. Married parents spend about 19% of their free time socializing with others, compared to 14% for single childless adults. Although these gaps may seem trivial, even small differences in time spent socializing with others can have a big impact on well-being.

Our well-being is not soley influenced by the activities we engage in but is also shaped by the social connections we maintain. Hence, even if married parents have less time for socializing and relaxation, they are much more likely to spend their time in the company of loved ones. Given what we know about the consequences of social isolation and the mental health benefits of being around family, differences in time with others could be driving the well-being gap between these two groups. Fortunately, the ATUS allows us to observe with whom each group spends their free time. Figure 4 shows the percentage of each groups’ free time spent alone.

As it turns out, single childless people spend 63% of their free time alone. Married parents, on the other hand, spend only 37% of their free time alone. This means, for instance, that even when married parents are relaxing or watching TV, they are often doing it in the presence of others, likely improving well-being in the process. In some sense, these findings should be self-evident—married parents typically live with their spouse and children and are therefore much more likely than single childless people to spend time with others. But in our era of rising social isolation and loneliness, the value of the presence of loved ones should not be undervalued. Moreover, it is also worth reiterating here that married parents spend about 10 more hours per week caring for others than single, childless adults. Though advocates of singleness may brand this as time that could otherwise be used to pursue one’s independent interests, time spent caring for others is also a correlate of improved well-being.

So what does this research tell us? First, single childless parents have significantly more free time than married parents, and spend more of that free time socializing or relaxing. However, we also see that married parents put their free time to better use—spending less time in front of a screen and more time socializing with others. Additionally, married parents spend most of their free time with others, whereas single childless adults spend most of their free time alone.

To be sure, differences in time use may simply reflect differences in preferences. But given the happiness gap between married parents and single childless people, it’s worth taking seriously the possibility that more free time might not lead to more happiness, and trading free time for family time may be integral for promoting well-being.

Thomas O’Rourke is a policy researcher and writer who studies social capital, economic mobility, and anti-poverty policy.