Highlights

Recent headlines about increasing gray divorces are scary, such as this one from the Pew Research Center, “Led by Baby Boomers, divorce rates climb for America’s 50+ population,” or this one, “'Gray divorce' affects millennials as parents split,” or this one, “Surviving Divorce after 50.”

But what’s really behind the so-called gray divorce phenomenon?

For the two of us, this is a personal issue. We’ve each been married for more than 30 years, and we are each (gulp!) over the age of 50, with college-age or older children. As we contemplate our empty nests and these reports, it is natural to wonder: Are our marriages in trouble? What is our own risk of divorce?

As a recent IFS post reported, “a sizable share of gray divorces (34 percent) occur among couples that have been married for over 30 years, and one-in-10 couples (12 percent) have been married for more than 40.” Yet, as that post also noted, there is a lot of nuance in the gray divorce statistics.

For our own comfort, and for the comfort of our Millennial children and their spouses and significant others—and for June’s (almost) one-year-old grandchild— we wanted to pull out some of the more important divorce trends. As we found when looking through a range of studies, divorce risk is not evenly spread among those aged 50 and older. Depending on your demographic, you may or may not be comforted by these trends.

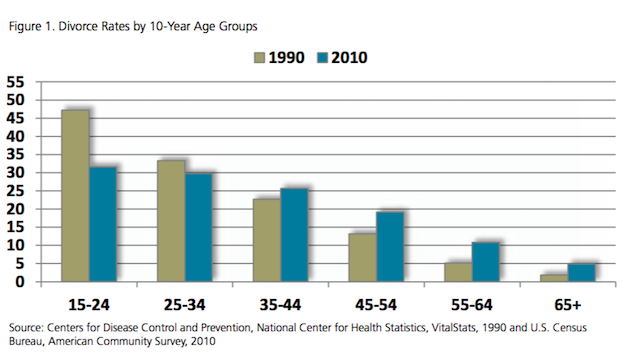

First, some good news for everyone: the divorce rate is still not all that high for those over the age of 50. Yes, it has doubled over the past 30 years: in 1990, five out of every 1,000 married people divorced, and in 2010, it was 10 out of every 1,000 married people. And yes, the rate has risen much more dramatically for gray Americans than for those under 50; in fact, there was a decline in the rate for those between the ages of 25-39. But the divorce rate for those over 50 is still half the rate for those under 50.

Source: Susan L. Brown, et al., "Age Variation in the Divorce Rate, 1990-2010," Family Profiles, NCFMR, FP-12-05.

Second, the triggering events for gray divorce are not what one might assume. One New York matrimonial lawyer who experienced a gray divorce himself speculated:

A lot of marriages died a long time ago, but because of the shame involved, in a family people often stuck together for the children. Now the children are grown up. Viagra is another reason—men are able to satisfy younger women. And people are living longer and they can get out and still have a life.

But that account isn’t necessarily accurate, according to research from a 2016 paper from the National Center for Family & Marriage Research (NCFMR) at Bowling Green State University, which also wrote the definitive paper on “The Gray Divorce Revolution” in 2012. The authors found that Baby Boomer divorce is not related to children leaving home, the retirement of either spouse, or even chronic illness; nor is it related to education—a result that surprised us, given our work. While for younger couples, the better educated are substantially less likely to divorce than those without college degrees, lack of education does not play the same role for those over 50.1 (Note: the 2012 research from the NCFMR, with a different dataset, does show a lower rate of divorce for those with a college education than without).

To tease out which variables are correlated with gray divorce, the 2016 study looked through the marital histories of more than 5,000 couples, where one spouse was born before 1960, using a longitudinal study of a nationally representative, continuous cohort, with interviews conducted every two years. They found that several factors were related to staying married. Couples who owned property together were less likely to divorce. And wealthy couples had a higher probability of staying together: “The odds of divorce were roughly 38 percent lower for those with over $250,000 in assets compared with couples whose assets ranged from $0 to 50,000.” The authors noted that “financial security” was a “protective factor” against a later-in-life divorce. The NCFMR’s 2012 research also noted the importance of economic resources.

Moreover, among these older couples, the 2012 study found that the divorce rate for those in a first marriage was less than half that for those who had remarried. Consider that although marriages of 40 years or more were the least likely to end, even among these couples, gray divorce was still almost three times higher for remarried couples than for first-married couples. The authors also believed that marital quality, measured by the couples’ evaluation of how they allocated their free time together and their level of enjoyment of that time, was a significant factor, although their data on this issue was limited.

These statistics don’t mean that gray divorce isn’t a problem. Those who divorce at older ages, like those who divorce at younger ages, tend to have less wealth than those who remain married, with the gray divorced having only one-fifth of the assets of gray married couples. Compared to married couples, gray divorced women have relatively low Social Security benefits and relatively high poverty rates. While gray married, remarried, and cohabiting couples have poverty rates of four percent or less, 11 percent of men who divorced after the age of 50 were in poverty, and 27 percent of the women were in poverty. And as Naomi and her co-author, Amy Ziettlow, have recently written, now that family structures have become increasingly complex, so, too, has elder care.

Of course, these statistics also don’t mean that our marriages will last forever. Statistics can only give a general picture, and can’t tell us whether our husbands will leave us—or whether we will leave them. Relationship quality, such as fostering “friendship” over the years, is also key to lasting marriages.

But looking at the numbers more carefully can help us assess our likelihood of getting divorced, and help us understand policy choices for older Americans. In light of the role of financial security, programs that enhance economic opportunities throughout the life cycle and lead to the accumulation of assets—programs that are productive under any measure—might also help with the gray divorce rate itself and with managing the consequences.

Naomi Cahn is the Harold H. Greene Professor of Law at The George Washington University Law School. June Carbone is the Robina Chair of Law, Science, and Technology at the University of Minnesota Law School.

1. The study states: "We considered three types of couple heterogamy: age, race, and education. Interracial couples experienced higher odds of divorce compared with same race couples. However, age or educational heterogamous couples were no more likely to divorce than their homogamous counterparts. There was no appreciable variation in the risk of divorce by education, which is consistent with other work indicating that education plays a modest role in gray divorce (Brown & Lin, 2012). Home ownership specifically and wealth more broadly served as barriers to divorce. Thus, financial security is protective against divorce.”