Highlights

- Where are the 10 biggest metro areas that are in the top 25% for both relatively affordable housing and the presence of young families? Post This

- As the ripple effects from COVID start to fade, making more communities attractive to couples and families who want to move should become a priority of any pro-family policy agenda. Post This

The long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the way we work and live is still uncertain, but that hasn’t stopped some commentators from proclaiming the “death of cities” and the rise of “zoom towns.”

Most of this rhetoric is overblown; instead of a great shake-up, the data show that coronavirus tended to amplify the patterns that were already happening—more growth in the Sun Belt and suburban metro areas, stagnant or falling population in expensive center cities and rural small towns.

But for some non-negligible pool of workers, the rise of remote work will open the possibility of getting out of expensive cities. Even as many companies begin to bring employees back to the office, certain jobs are extremely well-suited for permanent remote work, and firms facing a competitive labor market may offer additional flexibility for workers who are interested in moving out of their expensive 1-bedroom studio or 45-minute commute on the subway.

So what should all of these newly-mobile workers do with their newfound freedom? With the delay in marriage and fertility, many of those born between 1981-1996, often referred to as “Millennials,” are in the mid-20s to late-30s, their peak years for family formation. If you graduated college in the wake of the Great Recession and sought your fame and fortune in New York, San Francisco, or Washington, D.C., the time might be right to move to a place with a cheaper cost of living, which will make it easier to afford having a kid.

Some might want to move back to the hometowns either parent grew up in, to be close to grandparents or relatives with their attendant free babysitting or family dinners. But not everyone has a desire to return home (or, let’s face it, may not trust the relatives with the babysitting,) and may feel the call of the open road. If work is fully remote, where should aspiring parents move?

There is no shortage of “rankings” of family-friendly cities that clutter the internet, each with their own methodology and weighting of different factors. These are basically useless without knowing the preferences for each family. But seeing what kinds of cities meet a certain threshold for family affordability can be instructive from a policy perspective.

For new or would-be parents, the cost of housing may be especially burdensome. The price of housing has been shown to have a consistently strong relationship with fertility rates, impacting renters negatively and home-owners positively. Younger couples, who haven’t had enough time to save up enough money for a down payment, are hit harder by high housing costs.

But affordable housing is only one piece of the puzzle. If you’re a new parent, you might want to live near other new parents; not just because that indicates a place where kids are welcomed, but because of the higher likelihood of finding a church or playground or mom’s group in which you can find a piece of community.

Let’s take all Census-designated metropolitan statistical areas (defined as a population concentration with more than 50,000 in population), assuming that even the most mobile remote worker will want a place near an airport with regular connections. Now, let’s slice them on a couple key, family-friendly parameters: the median monthly cost of housing as a share of the median household income, for starters, and the share of households in the MSA with a young child (below the age of six) at home. We can then find the 10 biggest metro areas that are in the top quartile (top 25% of metro areas) for both relatively affordable housing and the presence of young families.

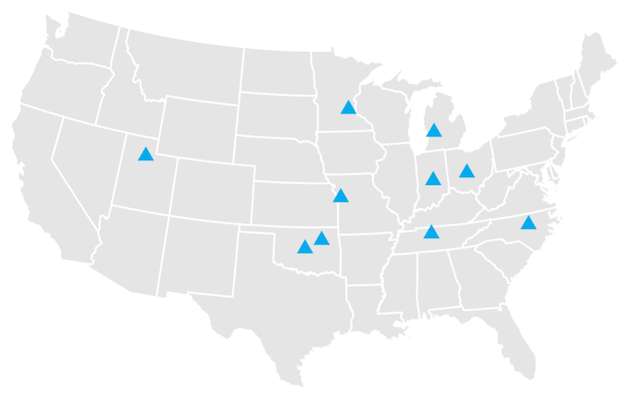

Figure 1: Ten biggest metro areas in both top quartile of households

with young children and relative housing affordability

If you’re leaving the coasts but still want a city with major industries and population hubs, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Columbus, Indianapolis, Nashville, and Salt Lake City all qualify, with Raleigh, Grand Rapids, Oklahoma City, and Tulsa making the top 10 as well. Note that these are all solid, not superstar, cities, offering an affordable cost of living around other families. Some, like Salt Lake City, Minneapolis, and Nashville, are considered on the rise, and may risk losing their relative affordability in the years ahead (but unlike the constrained cities on the coasts, may have a greater ability to expand outward.)

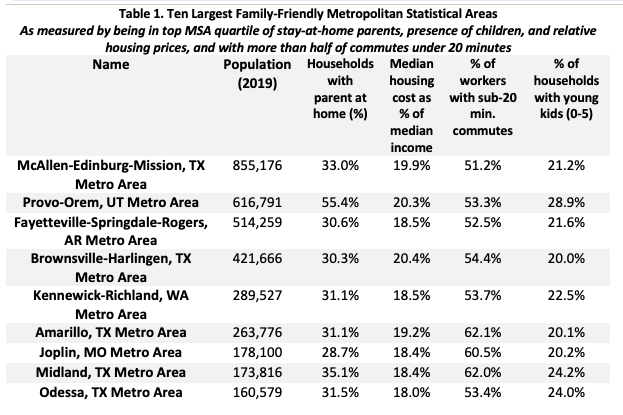

But we could add in a few other factors. Some families may want to take advantage of a cheaper cost of living to enable one parent to leave the work force. Those families might like to be around other families that have a parent out of the work force, to increase the odds of potential playdates. And, of course, if trips back into the office become a post-Covid necessity, families may prize making sure either or both spouses can still get to work without spending too much time in the car.

Adding those two parameters to our criteria, we can now select the 10 biggest metro areas in which half of workers report commutes of less than 20 minutes and are in the top quartile for the number of families with a stay-at-home parent, as well as the top quartile for relatively affordable housing and share young kids present as before.

The Lone Star state shines here, partly reflecting the burgeoning Hispanic population. Provo’s strong showing also makes sense thanks to the family-centered lifestyle of many adherents of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

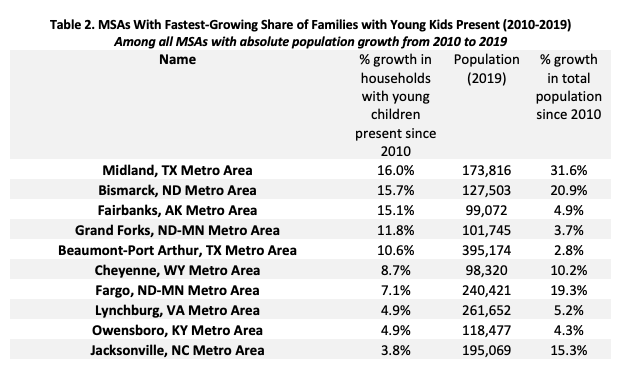

Lastly, we might want to know how other parents are voting with their feet. For the last table, we filter out MSAs that have experienced population decline since 2010, then find the 10 areas with the fastest growth of households with young kids present. The area around Midland, Texas has experienced some of the fastest population growth over the past decade, and the share of households with young children has increased the fastest there as well, up 16% from 2010 to 2019 (from 20.8% of households to 24.2%.)

Some of these places, like Alaska and North Dakota, have traditionally low rates of family formation reverting to the mean, while others are benefiting from robust economic growth that is also attracting families with young kids.

This quick-and-dirty tour through the types of places young parents might want to live doesn’t tell us everything important (schools and crime rates, perhaps most notably.) And, of course, there are other intangibles one might prefer in larger, more expensive cities—the shows, restaurants, plays, and pro sports. Plenty of would-be parents prefer the amenities of big city life and are willing to make trade-offs to afford them.

But those who like city life and want to be able to more easily afford having a family should probably look to the Midwest. And for couples who are okay with a smaller metro area but prize being around families with young kids, Texas awaits.

As the ripple effects from COVID start to fade, making more communities attractive to couples and families who want to move should become a priority of any pro-family policy agenda. Lawmakers who want to experiment with ways policy can support families should turn their eyes to these MSAs as places to experiment with truly family-centered policymaking.

Patrick T. Brown is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, working on family policy, and a a former senior policy advisor to Congress’ Joint Economic Committee.