Highlights

- To an important extent, the wealth divide in America coincides with a marital divide across the nation. Post This

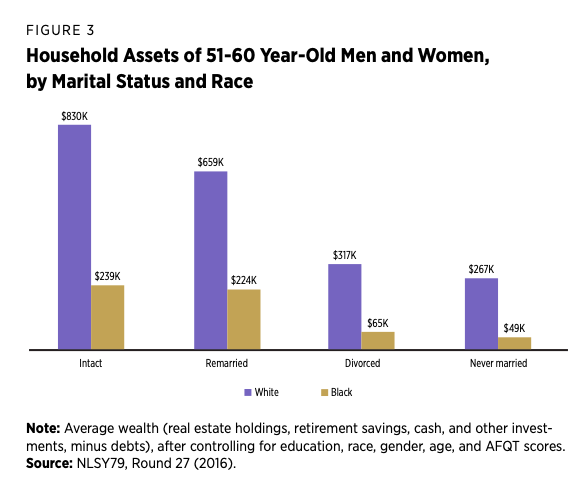

- Differences in wealth by family structure also apply across racial lines, with white and Black Americans who are married enjoying markedly more wealth than their unmarried peers of the same race. Post This

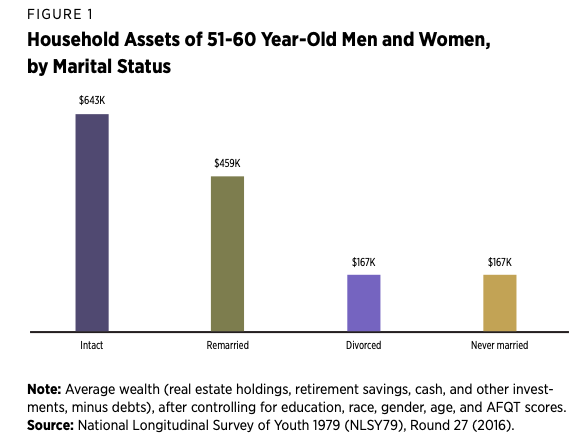

- Married Americans have more than twice the average assets of divorced and never married Americans. Post This

Editor's Note: The following essay is excerpted from The Future of Building Wealth: Brief Essays on the Best Ideas to Build Wealth—for Everyone (The Aspen Institute and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, September 2021).

The United States is an increasingly unequal society along many dimensions—including household wealth. For instance, a 10% minority of the country holds a majority of the household wealth (69%). As with so much of the social and economic inequality in the nation, there is an important family dimension to this inequality story. The significant minority of adult men and women who get and stay married are much more likely to hold greater wealth—when measured in terms of the assets they own (including homes, retirement savings and bank accounts) minus their debts. To an important extent, the wealth divide in America coincides with a marital divide across the nation.

In this essay, I use data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) cohort to explore the character of this marriage divide in wealth—as measured by real estate holdings, retirement savings, cash and other investments, minus debts—for men and women who are in their 50s and on the verge of retirement. I also cast an eye on how this divide plays out by race and class before concluding that, in order to bridge the marriage and wealth divides in the U.S., policymakers should pursue policies like means- tested “baby bonds” or universal savings accounts that will help more young couples feel financially prepared to marry while also rooting out marriage penalties from means-tested programs.

The marital divide in assets for 50-something adults is substantial. As Figure 1 indicates, married Americans have more than twice the average assets of divorced and never married Americans, even after controlling for gender, age, education, race, ethnicity and scores on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, a standardized test that measures mathematical, scientific and word knowledge. On average, stably married men and women have more than $640,000 in assets, while the remarried have more than $450,000 in assets. By contrast, divorced and never married Americans have only about $167,000 in assets when they reach preretirement years.

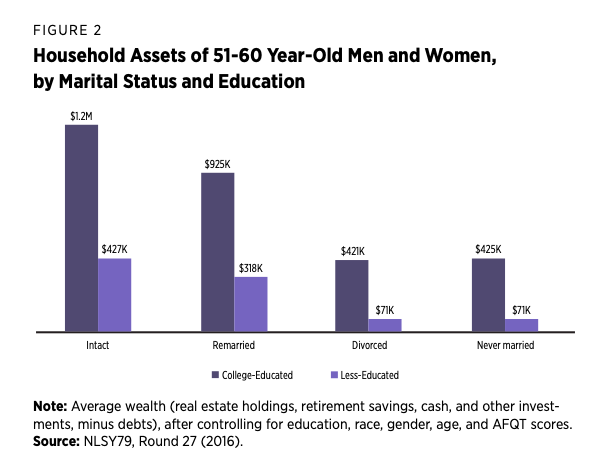

Large differences in wealth by family structure also apply within demographic groups in the United States. Among the college educated, those who are married have more than twice the wealth of those who are divorced or never married (about $1 million compared to $425,000) even after controlling for demographics (see Figure 2). Among the less educated, married Americans have about four times the wealth ($318,000-$427,000) of those who are not married (about $71,000). Thus, family structure is even more powerfully linked to wealth for less educated Americans than it is for highly educated Americans.

Differences in wealth by family structure also apply across racial lines, with white and Black Americans who are married enjoying markedly more wealth than their unmarried peers of the same race. Figure 3 indicates that white Americans who are married have more than twice the wealth (about $750,000) of their unmarried peers (about $300,000). Among Black Americans, the association between marital status and wealth is even larger, with married Black Americans having more than three times the wealth of their unmarried peers, about $230,000 compared to $65,000. Note, however, that even married Black Americans have less wealth, on average, than do unmarried white Americans. These descriptive results suggest marriage is not a panacea when it comes to addressing the racial wealth gap in America and that other factors are in play.

Undoubtedly, some of the substantial divide in U.S. household wealth associated with marital status is driven by selection. Americans with more income and assets are more likely to marry and to stay married. This is especially the case today with highly-educated men and women being more likely to be stably married than less educated Americans. As sociologists Pilar Gonalons-Pons and Christine R. Schwartz have noted, “the well-off are now ‘doubly advantaged’: they are both more likely to be married and thus have access to a second paycheck, and because of increased economic homogamy, they are also more likely to be married to another high-earning spouse,” all of which increases their ability to accumulate wealth. Moreover, some of the marital divide in wealth can be attributed to the fact that men and women who have particular personality traits and values—such as a long-term orientation to life—are more likely to save and be stably married. So, to some extent, other factors besides family structure per se—like education or prudence—help to explain the marital divide in assets.

On average, stably married men and women have more than $640,000 in assets, while the remarried have more than $450,000 in assets. By contrast, divorced and never married Americans have only about $167,000 in assets when they reach preretirement years.

Nevertheless, marriage and marital transitions also appear to independently influence the accumulation of wealth in America. Married couples, for instance, benefit from economies of scale that allow them to share housing, food and utilities and devote more of their household income to building wealth. Stably married couples also avoid the substantial costs associated with family instability, especially among parents—legal costs, child support and moving to a different home, to name a few. Furthermore, marriage itself appears to engender a responsibility ethic, where spouses set aside money for an imagined future together. This translates to higher rates of per capita savings and lower rates of spending per capita among the married compared to their demographically similar but unmarried peers. Because marriage makes it easier to save, reduces costs associated with family instability and engenders a savings ethic, the significant association between marital status and wealth looks to be at least partly causal.

Given the deeply unequal character of family structure and household wealth in the U.S. today, and the reciprocal relationship between wealth and marriage—where wealth appears to foster stable marriage and stable marriage seems to increase one’s odds of building wealth—two policy conclusions follow. First, policymakers should pursue measures—like “baby bonds” or savings accounts at birth that are funded more generously for more disadvantaged children and may be used once a child turns 18 for paying for college or technical education, buying a home or starting a business—that will reduce wealth inequality in America and help more young men and women feel financially prepared to enter into marriage. Second, policymakers should also seek to bridge the marriage divide in America by minimizing or eliminating marriage penalties in means-tested programs and policies that hit working-class families especially hard today. Medicaid and disability benefits, for instance, should be reformed so as not to penalize couples who marry.

Such policies will help engender a future where more financially struggling young men and women can marry at the age they want to and can tap into the many benefits of marriage—including increased ability to accumulate wealth. The alternative, a world where wealth and marital success is divided ever more unequally by class, is unacceptable.

W. Bradford Wilcox is professor of sociology at the University of Virginia, visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies.