Highlights

- A new study shows that the success sequence is a useful policy framework for helping unmarried mothers and their children. Post This

- At every year of the survey, the more success sequence milestones reached, the smaller the percentage that experienced poverty. Post This

- Even though only a relatively small share of unmarried mothers at childbirth eventually married, marriage later in life proved to be an important factor for reducing poverty. Post This

As covered on these pages before, the success sequence—graduating high school, working full-time, and marrying before having children—has been proven to be an effective way for young people to avoid poverty. Research consistently finds that young people who follow these life steps have poverty rates dramatically below those who do not follow these steps. In a new study, I show that the success sequence is a useful policy framework for helping even the most vulnerable avoid poverty—specifically, unmarried mothers and their children.

By definition, unmarried mothers did not follow the success sequence because they had a child outside of marriage. However, I wanted to explore whether achieving success sequence milestones later in life helped these mothers avoid poverty. It remains true that children in unmarried families are the most vulnerable to poverty: families headed by a single mother are almost six times as likely to experience poverty compared to families with married parents. To understand better the dynamics of families after a nonmarital birth, I explored 15 years of longitudinal data from the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (formerly called the Fragile Families Study).

The Future of Families study includes a representative sample of all births in urban areas (population over 200,000) in the late 1990s, with an oversample of unmarried mothers. I focused on the group of mothers who were unmarried at the time of the birth of their child and explored changes to their relationship status, employment status, and education level over the first 15 years of their child’s life. My focus on these three factors—education, employment, and relationship status—stems from the literature on the success sequence and my desire to understand how the evolution of these factors affects poverty rates.

To start, I explored official poverty rates and changes to relationship status. Almost half of unmarried mothers at childbirth experienced poverty in the early years after birth, although poverty rates declined modestly as the child approached school age. Still, the poverty rate among this cohort of unmarried mothers was 40% by year 15 of the survey.

Part of the reason for such high poverty rates stemmed from parental relationships. At the time of childbirth, half of the unmarried biological parents cohabited, while the other half lived apart. However, the relationship between biological parents broke down over time. By the time of the year 15 survey, only 17% of biological parents were married to each other and 8% still lived together. The remaining 75% were either single or formed a cohabiting or married relationship with someone else.

Poverty rates were much higher for mothers who remained single compared to those who married. Without controlling for any other factors, poverty rates for those who married were half that of poverty rates for those who remained single at each survey wave. By year 15, only 17% of married mothers were in poverty compared to 55% of single mothers.

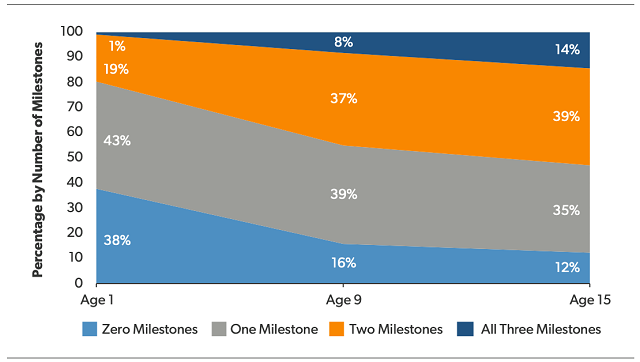

Despite high levels of relationship instability, some unmarried mothers in the Future of Families Study made progress toward success sequence milestones over time. For my purposes, I considered getting married after childbirth as a success sequence milestone. As shown in Figure 1, 38% of unmarried mothers at childbirth had not reached any of the success sequence milestones by the time the child was age 1, but this percentage reduced to 12% by the time the child turned 15. Still, only 14% had achieved all three milestones by year 15.

Figure 1: Number of Success Sequence Milestones Reached Among Unmarried

Mothers at Childbirth

Note: Data weighted to reflect births in large US cities.

Source: Waves 1–6 in the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (n.d.c.).

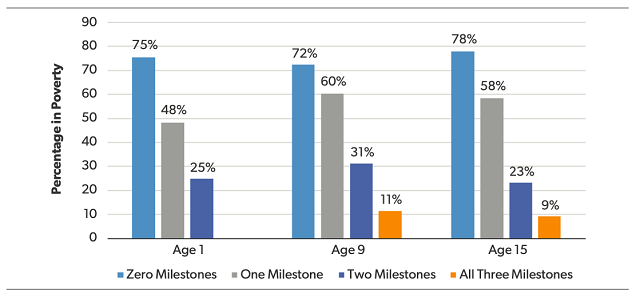

As unmarried mothers progressed towards success sequence milestones, their chances of being in poverty declined dramatically. For example, only 9% of mothers who had achieved all success sequence milestones by the time their child turned 15 were in poverty. For comparison, the poverty rate for unmarried mothers who achieved none of these milestones was 78% (Figure 2). At every year of the survey, the more success sequence milestones reached, the smaller the percentage that experienced poverty.

Figure 2: Poverty Rates by Number of Success Sequence Milestones Reached

Among Unmarried Mothers at Childbirth

Note: Data weighted to reflect births in large US cities.

Source: Waves 1, 2, 5, and 6 in the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (n.d.c.).

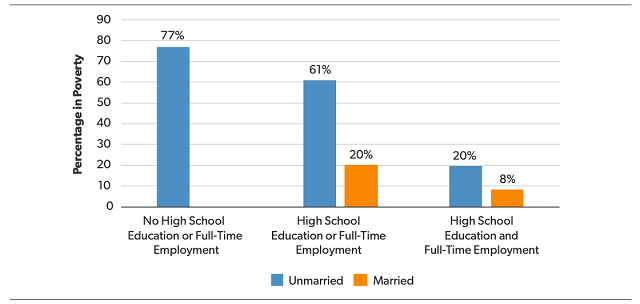

Even though only a relatively small share of unmarried mothers at childbirth eventually married—less than 30% were married by the time their child turned 15—marriage later in life proved to be an important factor for reducing poverty. Nonetheless, even among those mothers who remained unmarried, having at least a high school education and working full-time correlated to much lower poverty rates than having none or only one of these (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Poverty Rates at Age 15 Survey by Marital Status and Education and

Employment Milestones

Note: Data weighted to reflect births in large US cities.

Source: Wave 6 in the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (n.d.c.).

Some critics (and supporters) of the success sequence acknowledge that the ability to achieve success sequence milestones are often the result of circumstance. In other words, structural factors influence poverty more than individual choices. This study shows that despite the challenges surrounding a nonmarital birth, achieving success sequence milestones later in life, such as getting married, completing high school, and working full-time, offers families a realistic path out of poverty. Federal policymakers should prioritize these factors when designing safety net policies.

Angela Rachidi is the Rowe Scholar in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute where she studies policies that affect low-income children and families.