Highlights

In a recent University of Arizona Law Review article, Elizabeth Bartholet, a Harvard law professor, claims that the “homeschooling regime poses real dangers to children and to society.” Bartholet’s legal argument is that homeschooling is an infringement on child rights, placing children in inferior, socially isolating, and dangerous educational environments. This threatens democracy, she says, since homeschooling is not likely to provide the kind of civic education available in public schools, especially regarding democratic values. Besides the risk of child abuse and indoctrination, the strength of far right-wing religious conservatives in the homeschooling movement ensures that children will be forced into submitting to patriarchy, leading, Bartholet fears, to “female subservience.” If that wasn’t enough, she goes on to charge the homeschooling movement with links to white supremacy and racial segregation. According to Bartholet, the future of our democracy depends on “freeing” these children from unhappiness and ignorance.

Beyond the antecdotal “evidence” Bartholet provides, is there social scientific evidence that demands the “death penalty” for homeschooling? After considering the impact of the homeschooling movement on community involvement, diversity, and the dignity of the child, it is clear that Bartholet’s prosecution fails to overcome reasonable doubt.

For this analysis, I analyzed data from the 2016 National Household Education Survey (NHES), which included a random sample of 552 homeschoolers in America. I also drew on the Cardus Education Study (CES) findings, which surveyed large random samples of private schoolers, including homeshoolers, in the United States, who had graduated from high school and were between 24 and 39 years old in 2018.

Community Involvement

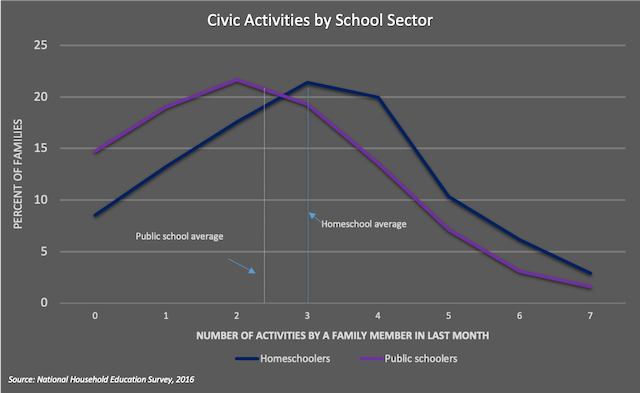

Bartholet claims that homeschooling “…parents…are ideologically committed to raising children in isolation from the larger society….” This analysis finds, however, that homeschooling children are part of families strongly linked to civic institutions and events. The NHES study included a battery of questions about community activities done by someone in the family in the last month, including attending a sporting event, attending a concert, going to the zoo or aquarium, going to a museum, going to a library, visiting a bookstore, or attending an event sponsored by a community, religious, or ethnic group. Added together, we find that homeschooling families have the highest level of community involvement of all school sectors.

This civic involvement not only strengthens social capital and trust within communities, but also provides a “hidden” or implicit curriculum important for civic socialization, which may carry into young adulthood. In the 2018 CES, about 22% of homeschooled young adults said they know a leader in their community, which compares favorably to the public school average (19). The total number of volunteer and community service hours for homeschooling graduates is very similar to or slightly higher than public school graduates.

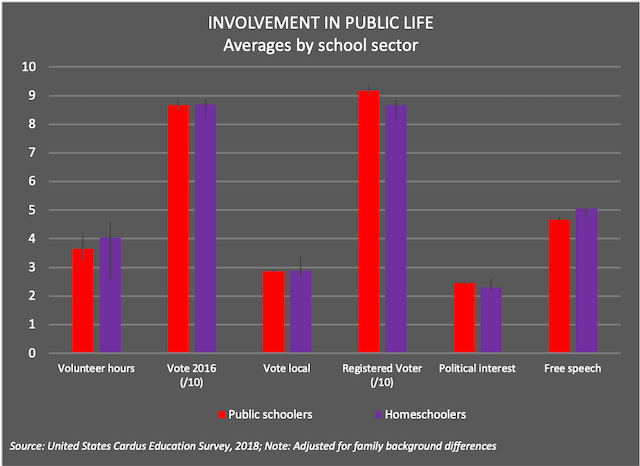

As an embattled political minority, we would not expect to find high levels of political participation among homeschoolers, except, perhaps, lobbying to defend homeschooling. Yet, according to the CES review of U.S. data, young adult graduates of homeschooling are nearly identical to public schoolers in their likelihood of voting in the 2016 presidential election.

Homeschooling graduates likelihood of voting in local elections is also identical to public schoolers. They are slightly less likely to be registered to vote, but the two sectors have very similar levels of interest in politics.

Bartholet seems to take the “home” in homeschooling too seriously, as if their windows have prison bars. In actual practice, homeschoolers are organized in complex networks with educational organizations, civic, religious, and cultural organizations, informal personal and virtual support groups, friendship circles, extended family, and so on.

Diversity

A second major problem is that Bartholet overlooks the striking diversity within homeschooling, focusing instead on incendiary anecdotes. “Some [homeschoolers],” according to Bartholet, “engage in homeschooling to promote racist ideologies and avoid racial intermingling.”

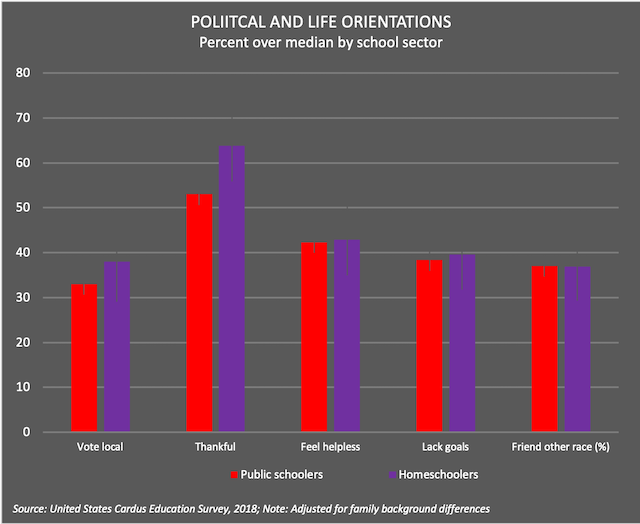

The reality is that about 41% of homeschooled children are racial and ethnic minorities. When asked about four closest friends, about 37% of young adult homeschoolers in the CES mention someone of a different race or ethnicity—exactly the same as public schoolers (see last figure near the end of this brief). The increasing segregation in public schools has perhaps removed any advantage for cross-race friendship ties in that sector.

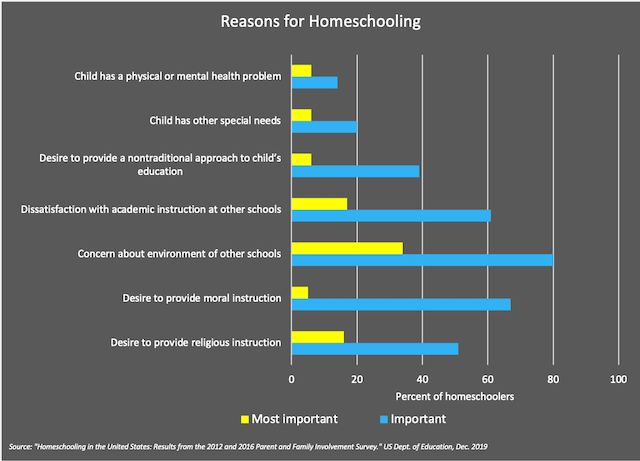

Data increasingly show that homeschooling is not a monolith, including considerable religious diversity. In the NHES, only about 16% say they are homeschooling primarily for religious reasons, and 5% for reasons of moral instruction. In the NHES national sample asking about reasons for homeschooling, only 51% cite religion at all, while 80% mention the school environment in other schools and 61% are dissatisfied with the academic instruction at traditional schools. Perhaps surprising to Harvard Law, but not to religion and education researchers, parents mentioning religion as a reason to homeschool are more educated than those who do not.

Homeschool graduates are not uniformly opposed to diversity in the public square, either. Bartholet claims that “a large percentage of homeschooling parents are committed to teaching their children that…democratic views and values are wrong.” The evidence is mixed at best. Homeschool graduates in the CES have higher levels of support for free speech norms than do graduates of public schools. Religious homeschool graduates are more likely than public school graduates to agree that a person should be free to express anti-religious ideas in the public square. Perhaps the experience of being an educational minority generates empathy for those who challenge convention, increasing support for key democratic values.

This diversity extends to schooling practices. Increasingly, homeschooling adopts surprising new forms, including “hybrids” that combine the benefits of home and institutional schooling. In fact, an estimated 57% of homeschoolers do not receive all of their education exclusively at home. Many of these are part-time public schoolers. In NHES, 32% of homeschoolers are receiving instruction at a public or private school or university. About 25% of homeschoolers receive instruction in public schools.

Homeschooling materials are not entirely from the dark ages either. About 32% obtain their homeschool curriculum or books from the public school or school district. Altogether, 46% of homeschoolers have some pedagogical relationship with public schools. If we include siblings who attend a public or private school, 58% of homeschooling families have a tie to public educational systems. These hybrid schooling experiences are likely to expand in a COVID-19 world. For this reason, Bartholet’s argument seems better suited for the late 20th Century, when homeschool-public school cooperation was in its infancy.

Child Dignity

Lastly, what about Bartholet’s view of homeschooling and child dignity? The homeschooled child is not locked up in a nuclear family prison, where girls are forced into “female subservience.” Their dignity is certainly not threatened by power dynamics more imposing than they would face in the social life and organization of public schools.

The homeschooling movement emphasizes the fit between schooling and the unique needs of a child at a particular stage of emotional and intellectual development, who may not thrive in a single environment for their entire schooling career. Consistent with this view, homeschooling is not the school of choice for the child’s entire elementary and secondary education. The NHES data reveal that only about 6 to 8% of homeschooled children spend all their school years at home. About 50% of homeschoolers spend less than half of their elementary and secondary school years in homeschooling. While Bartholet presents an image of authoritarian parents insisting on homeschool despite their child’s needs or wants, the reality is that most homeschooling families use various schooling options for each child.

Moreover, findings from the 2018 CES do not find homeschoolers bitter and lost. After family background and demographic controls are accounted for, about 64% of homeschoolers completely agree that they have so much in life to be thankful for (compared to 53% of public schoolers). Nor do we find that homeschoolers are different from public schools on feelings of helplessness, or lack or goals or direction in life.

Regarding dignity for girls, Bartholet claims that,

Some homeschooling parents are extreme religious ideologues who live in near-total isolation…some believe that women should be totally subservient to men and educated in ways that promote such subservience.

However, there is not support for the claim that religiously-conservative homeschoolers are patriarchal in their views of education. Using the NHES, I predicted the level of education homeschooling parents expected their child to achieve. The analysis tested whether, after demographic and family background controls, religious parents who homeschool favor the education of their boys over their girls. When using the civic/religious attendance as the measure of a religious home, the gender difference was small, favoring boys, but was not statistically significant. When using religious curriculum as a measure of religious homeschooling, the estimate of a gender difference in educational expectations disappeared. I do not find evidence that religiously conservative homeschoolers are opposed to higher education for their girls. Again, this is not surprising news, since sociology of religion scholars have long known that religious conservatives—along with everyone else—ignore their own scripts. Like evangelical Protestant home schoolers, religiously conservative homeschoolers are not walled off from dominant cultural trends.

Bartholet seems to take the “home” in homeschooling too seriously, as if their windows have prison bars. In actual practice, homeschoolers are “organized for instruction” in complex networks with educational organizations, civic, religious, and cultural organizations, informal personal and virtual support groups, friendship circles, extended family, and so on. The weight of bonding and bridging social capital matters for children, and the actual practice of homeschooling has many strengths on this score.

Traditional public schools continue to face imposing obstacles to achieving public purposes, especially as conceived by Bartholet. The question of schooling oversight remains, of course, but it would be short-sighted not to keep homeschooling and other creative schooling options in the mix, including the hybrid models that cross sector boundaries. In a COVID world, homeschooling may have something to teach us.

David Sikkink, Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Notre Dame, has studied school sector effects on civic, political, and educational outcomes of teens and young adults, especially through design and analysis of the Cardus Education Survey.

References:

Berner, Ashley Rogers. 2017. Pluralism and American Public Education : No One Way to School. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Beyerlein, Kraig. 2004. "Specifying the Impact of Conservative Protestantism on Educational Attainment." Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43(4):505-18.

Gallagher, Sally K. and Christian Smith. 1999. "Symbolic Traditionalism and Pragmatic Egalitarianism: Contemporary Evangelicals, Families, and Gender." Gender & Society 13(2):211-33.

Horwitz, Ilana M., Benjamin W. Domingue and Kathleen Mullan Harris. 2020. "Not a Family Matter: The Effects of Religiosity on Academic Outcomes Based on Evidence from Siblings." Social Science Research:102426.

Kunzman, Robert. 2009. Write These Laws on Your Children : Inside the World of Conservative Christian Homeschooling. Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press.

MacMullen, Ian. 2018. "Religious Schools, Civic Education, and Public Policy: A Framework for Evaluation and Decision." Theory and Research in Education 16(2):141-61.

NCES. 2019. "Homeschooling in the United States: Results from the 2012 and 2016 Parent and Family Involvement Survey." Vol. Washington D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics.

Sikkink, David and Jonathan Hill. 2016. "Religion and Education." in Handbook on Religion and Social Institutions, edited by D. Yamane. New York City: Springer.

Smith, Christian. 2000. Christian America? What Evangelicals Really Want. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wagner, Melinda Bollar. 1990. God's Schools : Choice and Compromise in American Society. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Wilcox, William Bradford. 2004. Soft Patriarchs, New Men: How Christianity Shapes Fathers and Husbands. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.