Highlights

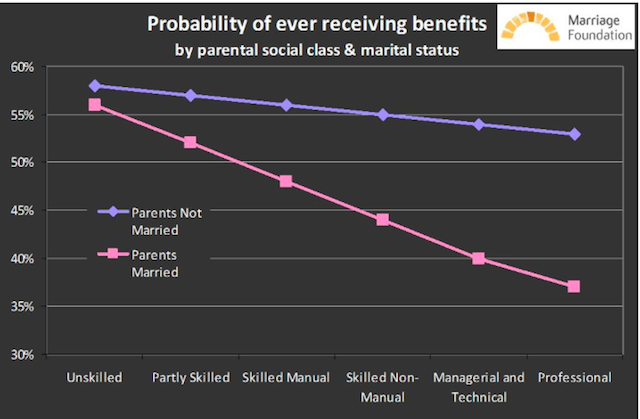

- In the UK, regardless of family and social background, those born to married parents were 16% less likely ever to have received government benefits as adults. Post This

- Having richer parents made no difference in the probability of ever needing to go on welfare if those parents weren’t initially married. Post This

One of the most common critiques of the supposed advantages of marriage is that married adults and their children only do better because of their education and money. The argument goes something like this: "It’s not marriage that conveys the advantages of life. It’s just that those who are better educated are more likely to get married. They then go on to make a success of their family and avoid many of the pitfalls. It’s a ‘mistake’ to attribute this to marriage, when really it’s all about education and money."

Alas, this ‘selection’ argument will be trotted out well beyond our lifetimes, since it is unlikely that anyone will ever persuade one group of people to marry and one group to stay unmarried and see who does best.

But the story to date is such that even when you account for education and money, and all sorts of other things that tend to characterize married rather than unmarried families, it’s rarely enough to explain why married families tend to do better. Compare rich families or poor families and the outcome tends to be the same. Married families still tend—on average, remember—to do better. We’ve shown this to be the case in a whole range of studies.

And, of course, there’s an excellent explanation for why married couples tend to stay together and unmarried couples don’t through the ‘sliding/deciding/inertia’ theory of commitment. (Read this pdf paper that explains the idea really neatly)

Anyway, one of my research colleagues—Professor Spencer James at Brigham Young University—and I decided we wanted to look at whether having married parents, rather than unmarried parents, has any long-term effect on life as an adult. We’ve already established that married couples are more likely to stay together. We’ve already established that the children of married adults are more likely to avoid things like mental health problems. In both cases, this is true regardless of parent’s age, education, and ethnicity.

But how long do these effects last?

To find out, we took a look at two British cohort studies that have followed the lives of 20,000 babies born in 1958 and 1970 who are all now adults in their late 40s and 50s. The timings are different for each cohort, but essentially these adults were asked all sorts of questions every five to 10 years.

This allowed us to compare those born to married and unmarried parents and also look at the social class of the parents when they were aged 16. We then looked at the children who later on got married, those who went to university, and those who needed to make use of benefits at any stage during adulthood to date.

Just to make sure we were looking at any effect of marriage, we also controlled for the child’s sex, mother’s age at birth, and mother’s interest in their child’s education at age 16, and any differences in outcomes between the two surveys.

The results of our study, which is now downloadable from the Marriage Foundation website, were extraordinary. Regardless of family and social background, those born to married parents were:

- 23% more likely to have been to university

- 10% more likely to have got married, and

- 16% less likely ever to have received government benefits

We also found the money effect. These things were also more likely to happen if the parents were in a higher social class, whether married or not, but with one exception: Having richer parents made no difference in the probability of ever needing to go on welfare if those parents weren’t initially married.

In other words, kids brought up in better-off homes are more likely to go to university and more likely to get married. But if the parents weren’t married, rich kids are just as likely to end up on government benefits as poor kids. There is no effect of money.

What is going on here?

Now it’s possible that children in two-parent families view life differently if the parents are not married. There are no anniversaries to celebrate. There may be higher levels of ambiguity about the relationship, and there are definitely differences in the way unmarried parents deal with conflict. What children witness then goes on to influence their need or willingness to rely on benefits.

But I think the more likely explanation is rooted in the higher levels of family breakdown experienced by children of unmarried parents. Even in families where one or both parents are university educated or white-collar workers, children will have seen the difficulty of managing the dissolution of family life. Even among well-educated parents, that might have included a stint on welfare benefits. Having seen that happen to their parents may then reduce the resistance to relying on the government. It may also be that a more relaxed attitude among some lone parents leads to a more relaxed attitude to going on benefits.

Regardless of the explanation, our findings are robust and striking and show at least one major area of life where having married parents has a big impact on the future lives of children, yet money appears to play no role whatsoever.

Harry Benson is Research Director of the UK-based Marriage Foundation and co-author with his wife, Kate Benson, of What MumsWant (and Dads Need to Know). An earlier version of this post appeared on the Marriage Foundation blog. This version has been edited with the permission of the author.