Highlights

Editor’s Note: The following essay is an excerpt from Promoting Skills, a new report by University of Chicago professor James Heckman published by the Archbridge Institute. It is reprinted here with permission.

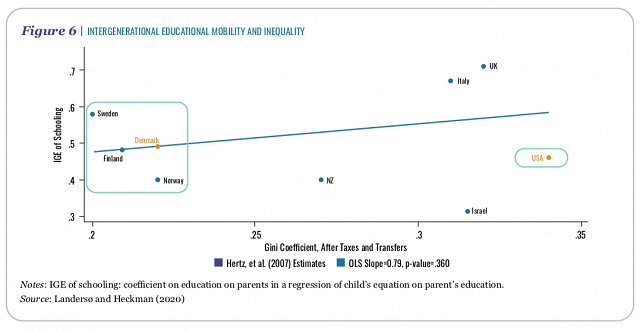

Data from Denmark supports the claim that differences in family structure perpetuate inequality. Denmark boasts universally high-quality schools with no apparent disparity in expenditure across regions or groups, yet the country has the same high level of educational inequality as the U.S. (see figure 6).

Despite universal and equal access to health care, childcare, free college and secondary schooling, there are large gaps in children’s outcomes between those of highly educated mothers and those of less educated mothers that are equally high in the US and Denmark (see figures 7 and 8 in the full report). In light of the equalizing policy of the Danish government in making expenditures on the schools in all neighborhoods, it can be surmised that family factors play a powerful role in perpetuating inequality.

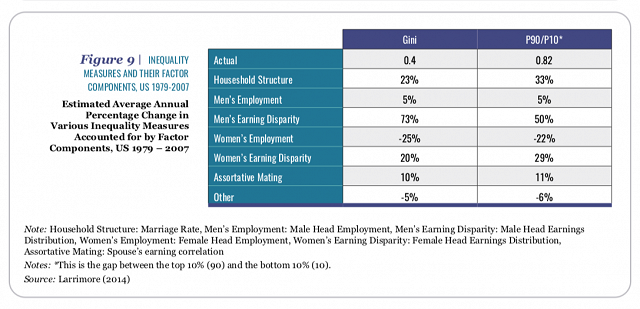

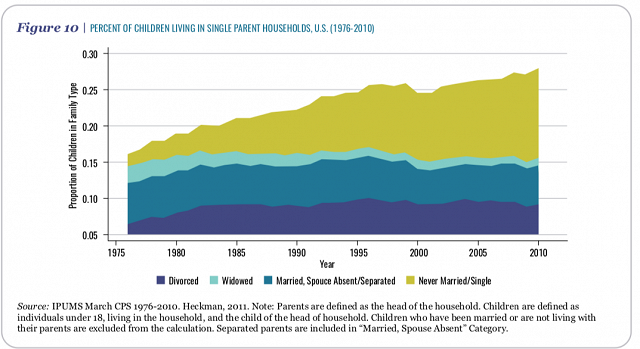

The Coleman Report (1966) in the U.S. demonstrated that family structure and family environment have a much stronger influence on learning disparities than school quality. Household structure plays a major role in shaping U.S. inequality. There is an inherent difference between single-parent households and two-parent households: on average, the single-parent household has fewer resources than a two-parent household. Single-parent families in which a child’s parents never married, usually have the mother as the sole earner. She is typically less educated and hence earns a lower wage. Single-mother households tend to have substantially fewer financial resources compared to nuclear families. In fact, modern American society’s highest family income quintile largely consists of two-parent families with both partners being high-earners and highly educated.

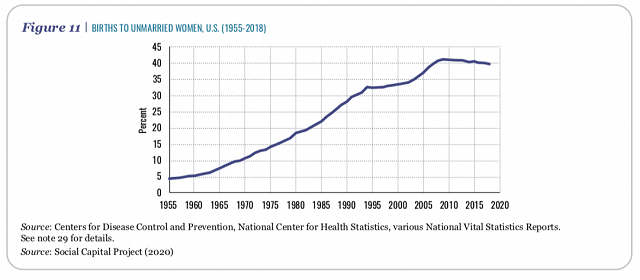

Inequality due to family structure is increasing as family life fractures. Between 1976 and 2016, the number of children under 18 living with a single parent rose substantially.

The number of births to unmarried women across all ethnic groups increased from 5% in 1940 to 40% in 2016. Such trends mean that less time and financial resources are devoted to the early development and learning of these children.

A 2011 study by Duncan and Murnane found that between 1972 and the late 2000s, the amount of money spent on children has greatly increased in households in the top income quintile but stagnated in house- holds in the bottom income quintile, leading to a vast and widening divide between the two groups. Given that families are the main producers of skills who impact children’s skill formation prior to when they attend schools, and considering the widening differential in family resources, it becomes clear that the gaps in children’s skill formation and other outcomes are driven by differences in family structures and environments.

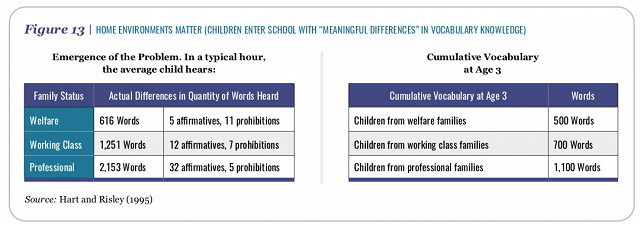

Today, more and more children are facing different household environments than those of the past, resulting in profound effects on their skill development. Beyond diminished access to financial resources, a 1995 study by developmental psychologists Hart and Risley found that children growing up in disadvantaged families suffer a learning disadvantage as early as age three.

For the children of disadvantaged families, the verbal environment consists of hearing roughly 600 words an hour. In comparison, children of highly educated parents might hear more than an average of 2000 words, roughly 3.5 times more words per hour. By age three, the cumulative vocabulary of a child living in a disadvantaged family is 500 words, far below the 1,100-word cumulative vocabulary possessed by a child from a professional family. The effects of this difference cumulate, resulting in the “30-million-word gap” at age five, popularized by Suskind et al. (2015). This early gap of basic skills tends to persist throughout life, leading to economic inequality and social immobility.

Assortative mating further exacerbates inequalities. Highly educated people marry other highly educated people, tend to live in separate neighborhoods, and create a more affluent environment for themselves and their families.

More generally, sorting is an issue in both the U.S. and Denmark. In Denmark, despite equal pay across schools, teachers with superior test score performance in college sort into the more affluent districts where kids have ample family support and resources and tend to be more motivated and easier to teach. In the U.S., sorting occurs more broadly within both the high and low ends of the income distribution, reinforcing many disparities that the education system and the tax and transfer system fail to address. Although governments lack the ability to intervene in personal family affairs and alter family structures and voluntary association of people, governments can enact policies that remedy underlying skills deficits caused by differences in family structures and socioeconomic backgrounds (see full report for a discussion of these policies).

In summary, there is abundant evidence that the persistence of poverty and inequality and differences in children’s educational outcomes are caused in part by differences in family structures and environments. American society needs to move beyond focusing on education as the producer of life-relevant skills and begin to promote social inclusion and social mobility by addressing skills gaps resulting from family differences.

James J. Heckman is the Henry Schultz Distinguished Service Professor in Economics at the University of Chicago. In 2000, Dr. Heckman shared the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on the microeconometrics of diversity and heterogeneity and for establishing a sound causal basis for public policy evaluation.