Highlights

- Around the world, women express a desire for more children than they currently have (on average). Post This

- In a new working paper, we show that women living in U.S. states with greater economic freedom also experience smaller fertility gaps. Post This

- Our findings suggest that states interested in pro-family policies should seriously consider looking into measures that expand economic freedom. Post This

Today, the primary cost of fertility is the cost of the mother’s time. As women’s education and employment opportunities have increased (both good things), the average woman forgoes greater earnings if she chooses to spend time raising children. In her excellent book, Career and Family, recent Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin analyzes these labor-market and familial changes for women over time. Unsurprisingly, birth rates have fallen—precipitously.

This is a troubling story not only because of the social costs of falling birth rates, but also because of the individual toll. Around the world, women themselves express a desire for more children than they currently have (on average). The difference between how many children a woman desires and how many she actually will have is referred to as the fertility gap. The fertility gap is positive when women desire more children than they end up having, and importantly, it represents a goal for nonpaternalistic pro-family policy (i.e., policy that works with people’s desires rather than against them or to change them).

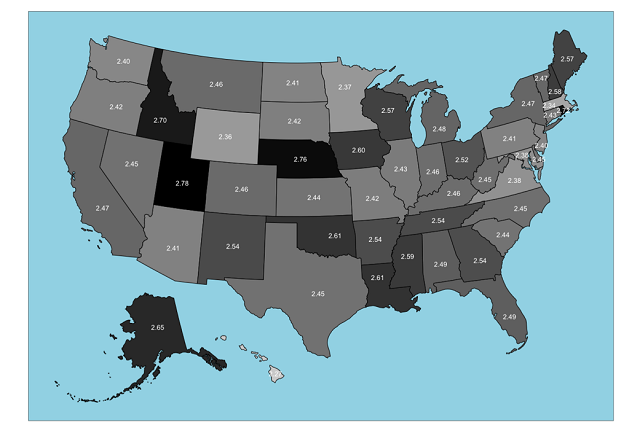

Below is a map of desired fertility across the U.S. states. The measure for desired fertility used in this context is called happiest parity, which is calculated as a weighted average of reported levels of happiness across outcomes of 0-6 children. The highest reported happiest parity is 2.78 children in Utah, while the lowest is 2.27 children in Hawaii. Notably, all state averages of happiest parity scores are above replacement fertility (2.1 children).

What is keeping women from fulfilling their fertility goals? In a new working paper, IFS research fellow Lyman Stone and I show that women living in U.S. states with greater economic freedom also experience smaller fertility gaps. This means that women growing up in an environment of more economic choice are also more likely to choose having a number of children closer to their desired family size (increasing fertility overall).

This is an intuitive finding, since it makes sense that having more choices leads to more women choosing to fulfill their desires both for careers and for families. However, it highlights an important fact about the contemporary American labor market: women’s education and employment are not necessarily in competition with family life. Important recent research from economists also reveals that this is not an America-specific trend—rather, in countries around the world, overall fertility is now positively correlated with women’s labor force participation rates.

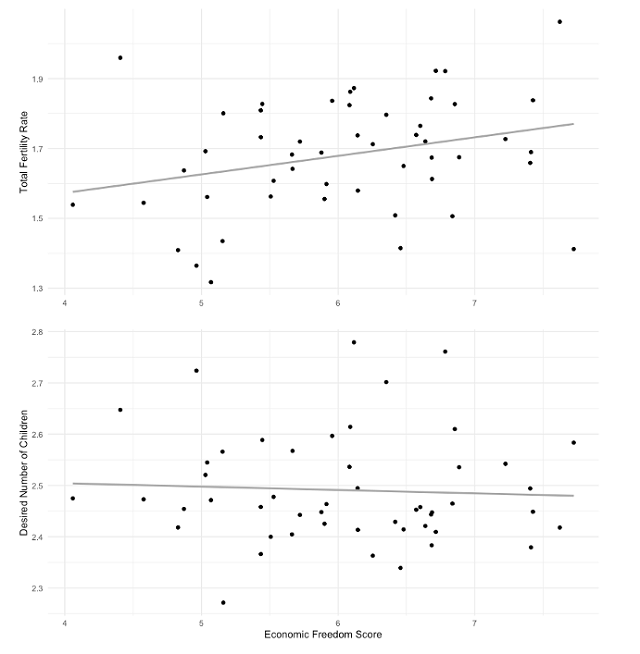

To investigate these patterns, we first correlated the Fraser Institute’s economic freedom scores with actual/desired fertility across the U.S. states. Economic freedom scores of individual states are assessed using three components: 1) government spending, 2) taxation, and 3) labor market freedom. While economic freedom is fairly uncorrelated with fertility desires, it is positively correlated (0.29) with actual fertility (measured by the total fertility rate).

Next, in our empirical estimations, we can control for variables such as median household income, marriage rates, religious service attendance rates, and foreign-born rates, all of which have been shown to impact fertility. Our resulting estimation reveals that a one-standard deviation increase in economic freedom (e.g., New York becoming more like Ohio) would decrease the fertility gap by 30% of a standard deviation (e.g., Minnesota having a fertility gap more like Kansas’s).

We also show that it is not personal freedom—measured by both pro-life and pro-choice personal freedom indexes from the Cato Institute—but economic forms of freedom that have this effect on fertility gaps. Perhaps counterintuitively, pro-choice personal freedom may even have a positive relationship to the fertility gap, exacerbating the gap between women’s desire for children and their actual family size. On the other hand, Cato’s measure of regulatory freedom, which measures labor-market freedom and occupational freedom (amongst other things), predicts smaller fertility gaps just as well as our main measure of economic freedom. This suggests that parents having a greater choice of careers, rather than a lower annual tax bill (both of which increase economic freedom), may be what is driving our results.

Our results raise a variety of interesting questions. While we speculate that economic freedom could mean better work-life compatibility for parents, we cannot know for sure from our data. It also might be because economically free environments are more competitive, nudging employers to be more family-friendly since this is something that employees value. Or, perhaps there is a third omitted variable raising both economic freedom and fertility, such as social capital. Regardless, our findings suggest that states interested in pro-family policies should seriously consider looking into measures that expand economic freedom.

Clara E. Piano is Assistant Professor of Economics at Austin Peay State University.