Highlights

- There are striking differences among Americans in both how COVID-19 has re-oriented their interest in marriage and childbearing, as well as who has specific plans to get married or have a baby. Post This

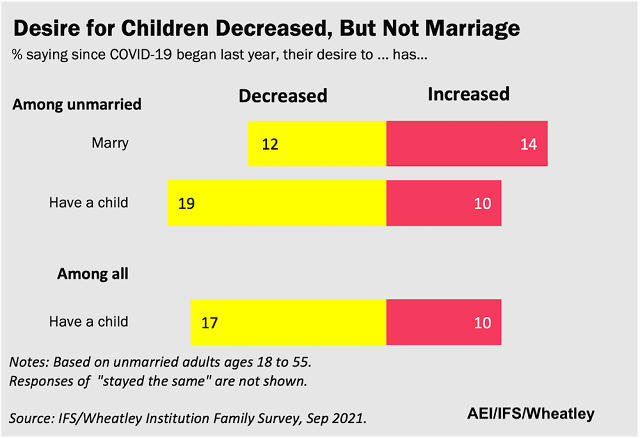

- Interest in marriage among unmarried Americans looks stable and appears to have even ticked slightly upwards. But the share of Americans aged 18-55 reporting that their desire “to have a child” in the wake of COVID-19 moved downwards. Post This

- Where is the American family headed as COVID-19 finally seems to be abating? Our new report addresses that question. Post This

The fortunes of the American family were falling when COVID-19 hit last year. Marriage and fertility rates were headed to new lows. A record share of today’s young adults were projected to never marry and never have children. In fact, partly because of the pandemic’s fallout, marriage and fertility rates hit record lows in 2020. Last year, the marriage rate fell to 33 per 1,000 unmarried population and the total fertility rate fell to 1.64 per woman—levels never seen before in American history.

But where is the American family headed as COVID-19 finally seems to be abating? On the one hand, the pandemic may have delivered yet another blow to American families already reeling from the economic and cultural forces of late modernity. The lives lost, the social and emotional fallout from the lockdowns, the economic dislocation, and the political turmoil of the last year-and-a-half have taken a toll on ordinary Americans. COVID-19’s effect on socializing, jobs, and Americans’ emotional equilibrium in the last year would seem to have undercut the social opportunities, cultural confidence, and economic resources required either to tie the knot or welcome new life. This is the “decadence-deepens scenario,” in the words of journalist Ross Douthat, where the “pandemic took trends inimical to family life and turbocharged them. From this perspective, family formation is likely to fall further in the wake of the pandemic.

On the other hand, in the face of trauma and tragedy, people often develop a new appreciation for family. We know, for instance, that millions of husbands and wives saw their commitment to one another deepen last year amidst COVID-19’s darkest hours.And when it comes to desiring marriage or a child, the existential and ontological questions raised by the pandemic may have raised the appeal of getting in the family way. Likewise, the sense of loneliness experienced by millions during COVID-19 lockdowns may have also made the prospect of getting married, or having a baby, more attractive or even necessary. There is a palpable thirst out there, in many quarters, for in-person, human connection. An alternate possibility, then, is that COVID-19 has jumpstarted people’s interest in our most fundamental social institution, the family. This is the renaissance scenario, and it would lead us to expect family formation to spike in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Our new report, The Divided State of Our Unions: Family Formation in (Post-)COVID America finds more evidence for the former thesis than the latter. On the one hand, interest in marriage among unmarried Americans looks stable and appears to have even ticked slightly upwards. According to a new IFS/Wheatley Family Survey conducted by YouGov in September of 2021, 14% of unmarried Americans ages 18-55 said their “desire to marry” has increased since the onset of COVID-19, compared to 12% who said it decreased. On the other hand, the share of Americans aged 18-55 reporting that their desire “to have a child” in the wake of COVID-19 moved downwards, with just 10% reporting an increased desire for children compared to 17% indicating their desire fell.

At least in the near term, then, COVID-19 seems to have made many Americans less inclined to welcome a baby in a world turned upside down by a global pandemic. A straightforward interpretation of these changes is that COVID-19 made people more deeply appreciate both the importance of the community inherent in family life (marriage), as well as its challenges (raising children). So, no consistent evidence in favor of the decadence-deepens or renaissance scenarios.

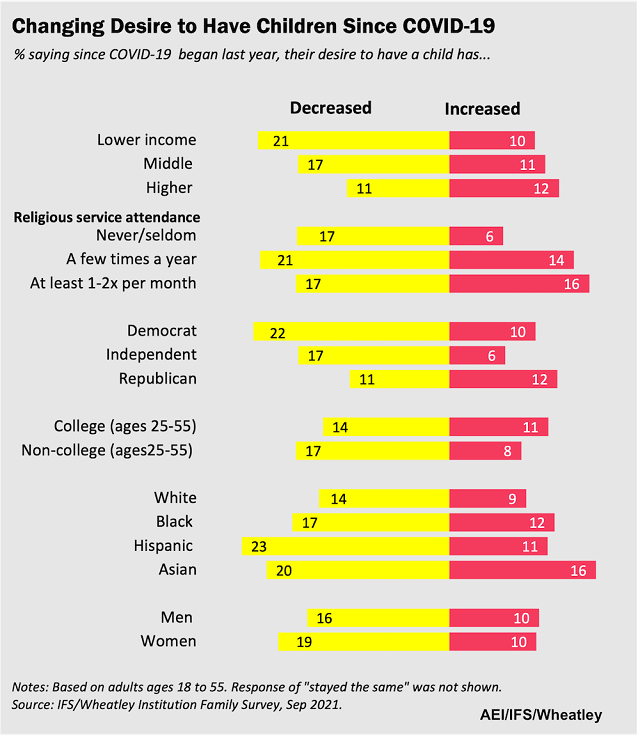

Beyond COVID-19’s overall effect on family formation in the United States, the pandemic may have also poured fuel on the family divides that preceded the pandemic. In a world where both marriage and fertility have become increasingly seen as unattainable or optional, three ingredients have emerged as signally important for family formation in the United States: money, hope, and a deep dedication to family—what we call “familism.” (Familism is the idea that marriage, childbearing, and family life are fundamental, and require a willingness on the part of individuals to sacrifice their own desires for the needs of their families.) Given the importance of money, hope, and familism, we also explore how interest in family formation varies by income, religion, and partisanship. In other words, we look at the possibility that a family polarization scenario is deepening, where COVID-19 is magnifying differences by class, religiosity, and partisanship in family formation. In this scenario, we would see a deepening divide between the affluent and everybody else, between the religious and the secular, and between Republicans and Democrats in their propensity to marry and have children.

In this report, we find plenty of evidence in favor of this scenario. There are striking differences among Americans in both how COVID-19 has re-oriented their interest in marriage and childbearing, as well as who has specific plans to get married or have a baby. In short, it appears that the tumult and turmoil occasioned by COVID-19 has only deepened the relatively greater propensity of the Rich, the Religious, and Republicans to move forward with marriage. Likewise, interest in having children has also been further polarized along religious and partisan lines.

But we also see evidence that interest in having children has declined more among the poor, possibly reflecting greater concern among them about the financial uncertainty unleashed by the pandemic. This would depolarize trends in parenthood since the poor have traditionally been more likely to have children than other Americans. But in most ways, as this report makes clear, COVID-19 appears to have amplified pre-existing family fissures in the American landscape.

Download the full report . . .