Highlights

In a modest neighborhood in West Virginia, there is a family that might be called “working class,” except that neither the father nor the mother work. Both are divorced and have issues with depression and alcohol and drug abuse. They have four children, ranging in age from 7 to 15, who have experienced bouts of domestic violence in their home.1

Although they may not have voted for him, these parents are about to receive an unexpected present from President Biden and the Democrat-controlled Congress. As part of the latest COVID 19 stimulus legislation that was just passed and promptly signed into law, they will be getting monthly checks for $1,000 for at least a year and, if progressives have their way, in future years as well.

The money will be sent to them as part of an expansion of the "Child Tax Credit." It comes on top of the one-time COVID stimulus checks and the Food Stamp funds and Medicaid benefits the family is already receiving. One may hope that the parents mentioned above will spend the new money on their children, but there is nothing to prevent them from spending it on drugs.

The expansion of the tax credit program to include non-earners and non-taxpayers with children was justified on the grounds that it would lead to a substantial reduction—perhaps even a halving—of child poverty in the country. But the idea that providing cash payments to parents with no strings attached constitutes an effective anti-poverty program has been sharply criticized as an undoing of hard-fought and constructive welfare reforms.2 As Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) wrote before the new law was enacted: "There is substantially more to lifting families out of poverty than government-provided income, and for decades, there was a bipartisan consensus that work, marriage, and community were critical pieces of poverty reduction."

Likewise, Oren Cass, executive director of American Compass, wrote in a New York Times opinion piece:

Money itself does little to address many of poverty’s root causes, like addiction and abuse; unmanaged chronic- and mental- health conditions; family instability; poor financial planning; [and the] inability to find, hold or succeed in a job... Effective anti-poverty policy provides resources in ways that also help resolve such problems and push the recipient toward resolving them himself.

Paychecks, Not Handouts, Are Key

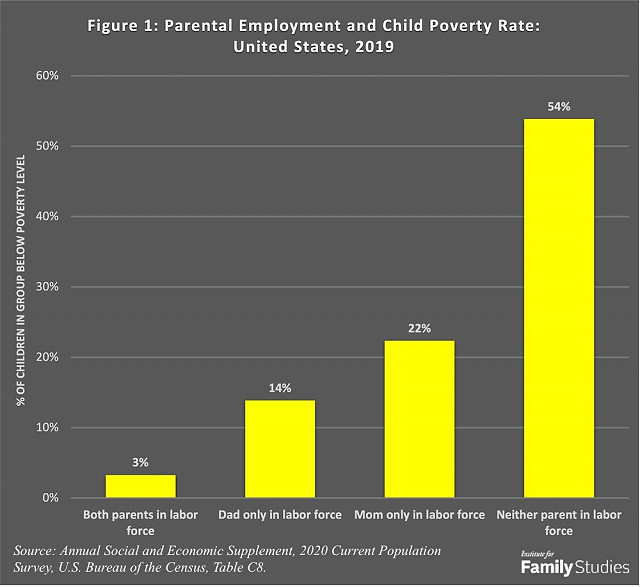

Support for the contention that bolstering parental employment is key for long-lasting poverty reduction may be found in recent Census Bureau data on child poverty.3 As may be seen in Figure One:

- During 2019, the child poverty rate was low—3%—among the 32 million children whose mother and father were both in the paid labor force (and were both living in the household).

- The poverty rate was nearly five times higher but still about average—14%—among the 18 million children who had only their fathers in the labor force.4

- The poverty rate was seven times higher—22%—among the 14 million children who had only their mothers in the labor force.5

- The poverty rate was 18 times higher—54%—among the 5.5 million children who had neither parent in the labor force.6

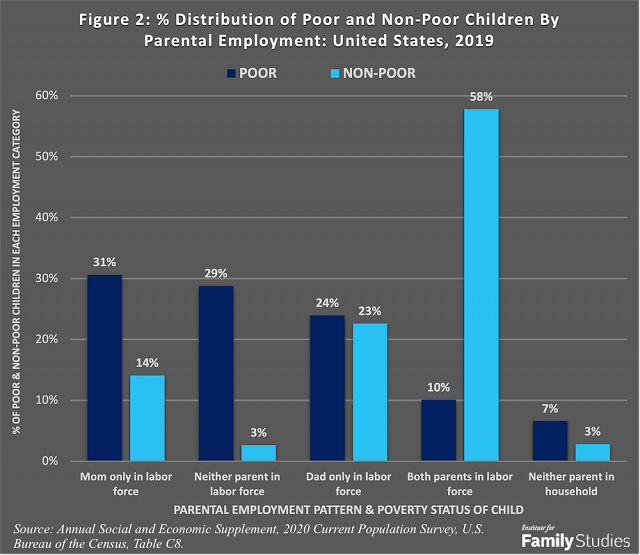

Despite the obvious financial advantages of having parents work, only 10% of children in poor families in 2019 had both parents in the labor force and contributing to the child’s upkeep. Three times that proportion—29%—had neither parent in the labor force. By contrast, among non-poor children (those whose family’s income was twice the poverty level or more), 58% had both parents working and only 3% had neither parent in the labor force.7

Pre-COVID, Employment Was Up, Poverty Was Down

Before the pandemic struck, employment among vulnerable families with children was going up and child poverty was going down. In 2019, the child poverty rate reached record lows: 10.5 million children, or 14% of all U.S. children, were in families below the official poverty line, compared to 16.3 million, or 22%, in 2010. Poverty was decreasing among all major racial and ethnic groups, with the greatest declines among Black and Hispanic children.

The outbreak of the pandemic led to sharp increases in parental unemployment and non-participation in the labor force, especially among mothers and parents of both sexes who had been in relatively low-wage, low-skill occupations, with a consequent rise in child poverty. But many jobs shut down by the pandemic have reopened or will soon do so, and growing numbers of mothers and fathers are working or looking for work again. Sending parents money whether they participate in the labor force or not is hardly calculated to provide a positive incentive toward starting or resuming paid employment.

Marriage, Family Stability, & Parental Cooperation: Other Keys to Poverty Reduction

Census data on child poverty also support the thesis that marriage, family stability, and parental cooperation are important for preventing financial hardship.8 Consider the following:

- During 2019, the child poverty rate was low—6%—among the 49 million children living with two parents who were married.

- The poverty rate was twice as high—15%—among the 3 million children living with their fathers only.

- The poverty rate was six times higher—34%—among the 15 million children living with their mothers only.

- The poverty rate was also six times higher—37%—among the 3 million children living with two unmarried parents.

- The poverty rate was nearly five times higher—28%—among the 3 million children who lived with neither parent, but with grandparents or other relatives or unrelated foster parents.

Although poverty rates were elevated among all types of single-mother households, they were less so among children living with divorced mothers—21% in poverty—than among those living with separated or never married mothers—40% in poverty. One reason for this is that divorced mothers, in general, tend to be better educated and to have agreements with their former spouses regarding child support and visitation.

Confronting Other Forms of Poverty

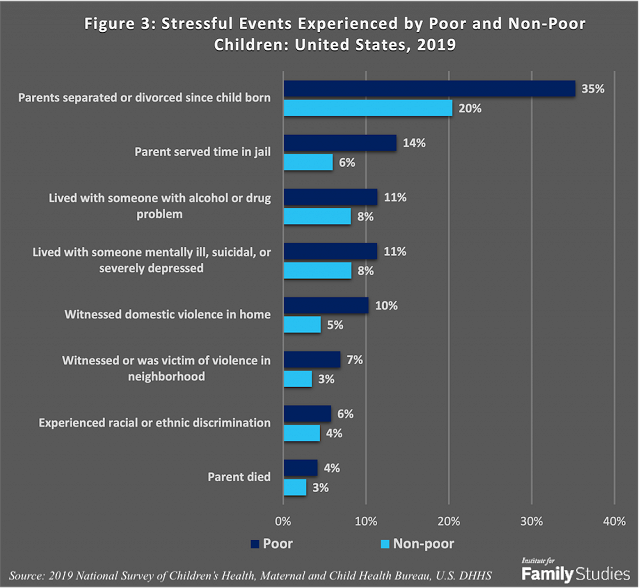

Improving children’s circumstances also requires efforts to deal with “behavioral poverty,” that is, family actions, generational cycles, and life choices that lead to or exacerbate financial hardship and other social problems. The reality of behavioral poverty is shown by the large numbers of American children who have experienced stressful life events with financial consequences. According to the 2019 National Survey of Children’s Health, of the 73 million children under the age of 18:

- 17 million had parents separate or divorce since the child was born.

- 9 million lived with a family member who abused drugs or alcohol or was mentally ill.

- 5 million had a parent spend time in jail.

- 4 million experienced domestic violence in the home.

- 3 million experienced violence in the neighborhood.

- 2 million had a parent die.9

As shown in Figure Three, each of these stressful life events was more common among children in poor than in non-poor families. Moreover, most of the events significantly increased the chances that a family with children would be poor. Children who had a parent jailed, or experienced domestic violence or neighborhood violence were twice as likely to be in a family whose income was below the poverty level, compared to children who had not experienced these events. Children whose parents divorced were one-and-three quarters more likely to be in a poor family. Children who had a parent die were one-and-a-half times more likely to be poor. And children who lived with a drug abusing or mentally ill family member were one-and-four-tenths more likely to be poor. The more stressful events the child experienced, the higher his or her chances of living in poverty.

Dealing with destructive parental behavior like alcohol or drug abuse is obviously a more challenging task than simply providing parents free money. Indeed, giving an addicted parent more cash (without other resources and support attached) may actually make matters worse. Although the stress of financial destitution certainly may provoke some negative behavior, like conflict between parents, there are usually other reasons behind such conflict as well. To produce lasting changes, underlying issues must be dealt with directly, with additional supports and oversite attached, not papered over with cash.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.

1. Actual family drawn from the anonymized public use file of the 2019 National Survey of Children’s Health. See note xvi.

2. Haskins, Ron. (2006). Work Over Welfare: The Inside Story of the 1996 Welfare Reform Act. Brookings; "Child tax credit expansion sets up showdown with GOP,” by Alexandra Jaffe & Josh Boak. Associated Press, Tuesday, March 9, 2021.

3. Author’s analysis of data from: Table C8. Poverty Status, Food Stamp Receipt, and Public Assistance for Children Under 18 Years by Selected Characteristics: 2020. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Internet Data Release: December 2020.

4. The denominator includes children in households where both parents were present (15.1 million children) and those where only the father was (2.9 million children).

5. The denominator includes children in households where both parents were present (2.5 million children) and those where only the mother was (11.8 million children).

6. The denominator includes children in households where both parents were present (1.6 million children) and those where only one parent was (3.9 million children).

7. See note vii. Ibid.

8. See note vii. Ibid.

9. Author’s analysis of public use data from the 2019 National Survey of Children’s Health. United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB).