Highlights

1. Fertility will continue to decline in below-replacement fertility countries: Myth.

A large number of studies have documented that the motivation to experience parenthood is deeply rooted, and even as the financial and opportunity costs of having children increase, individuals and couples sufficiently value parenthood to devote considerable time and financial resources to having children.

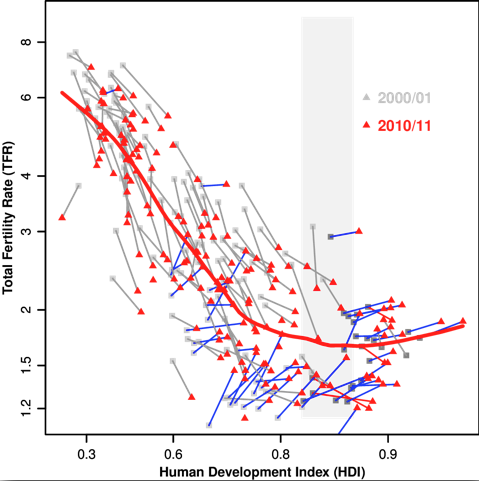

Fertility may even have increased among the most developed countries in recent decades, and the most educated women in some countries have experienced rises in fertility rates. Affluence, at the individual and at the societal level, may therefore have been a precondition for countries to achieve relatively high levels of fertility (within the overall low-fertility context of today’s Western European and North American countries). As the below figure shows, the relationship between the total fertility rate and the Human Development Index (HDI), a measure of social and economic well-being, varies from country to country. The least developed countries have the highest fertility rates, and fertility falls in less-developed countries as they advance socially and economically. But as countries reach very high levels of HDI, the HDI-TFR relationship becomes flat or even positive. This suggests that once low-fertility countries reach very high levels of HDI, they may see a leveling off of fertility or even a partial reversal of earlier fertility declines to very low levels.

At advanced levels of development, then, governments might explicitly address fertility decline by implementing policies that improve gender equality or the compatibility between economic success, including labor force participation, and family life. Failure to address these issues might explain the exceptional pattern for rich eastern Asian countries that continue to be characterized by a negative HDI-fertility relationship.

2. Low fertility results from low desired fertility: Myth.

Desired fertility in almost all developed countries hovers around 2.0 to 2.2 children per woman (though it sits at 2.6 in the U.S.). A two-child ideal has become nearly universal among women in all parts of Europe, and countries that used to display higher ideal family size have converged over time toward a two-child model. The large variation in fertility in Western countries, from 1.4 children per woman in Greece and Italy to 2.01 in the U.S. and 2.08 in France, is thus not primarily due to differences in desired fertility; it is due to the extent to which desires for children are realized. This extent depends on social and political institutions, labor market conditions and policies, gender norms, and cultural factors.

3. Low fertility necessarily implies high rates of childlessness: Myth.

Demographic analyses suggest that decline in people’s desire to have at least one child has not been a primary driving force behind the very low fertility in Southern, Central and Eastern European countries. While childlessness is likely to rise, it is projected to remain at relatively modest levels. Projected levels of childlessness in many very low-fertility countries, including in particular Italy and Spain, are comparable to the corresponding estimates for Sweden and the Netherlands in the late 1990s. And these levels are modest in a historical twentieth-century perspective or when compared to the childlessness observed in certain countries, as for instance Germany, where more than a quarter of the women in recent cohorts are estimated to have remained childless. These findings suggest that even in areas with the world’s lowest fertility rates, the biological, social and economic incentives for children are sufficiently strong that most women (or couples) desire to have at least one child.

4. “Thirty is the new 25”: True.

The mean age of entering parenthood has been rising across developed countries, and it has risen most rapidly in some Western European countries with the lowest levels of fertility. For example, in the Southern European countries, postponement has been very intense with annual increases in the mean age exceeding 0.2 years of age per year during the 1990s. In Spain, for example, the age of the average first-time mother was less than 25 years in the 1970s, but increased to more than 30 in recent years. The rapid postponement of fertility in many European countries has led to some of the highest mean ages at first birth worldwide. Hence, something that was common when women were in their mid-twenties is increasingly becoming typical for when they are in their mid-thirties: the rearing of and caring for the first child.

5. Parents enjoy parenting: The jury is still out.

Most individuals in Europe and North America who have children do so intentionally. But evidence on whether parents enjoy parenting is mixed. Conventional wisdom arguably suggests that parenting is satisfying for parents: individuals in early to mid-adulthood often claim to look forward to having children, and even where childbearing has become financially expensive and associated with considerable professional and personal trade-offs, childbearing has remained an important aspect of life to most adults. Yet in recent years, many have questioned the notion that children and childrearing increase the subjective well-being of their parents, and the scientific literature on the contributions of children to parents’ well-being reaches mixed conclusions.

On the one hand, the findings are broadly consistent with evolutionary psychological and biological theories that claim to explain people’s motivation to have children and form long-term partnerships. In particular, besides establishing the basic contribution of children and partnerships to well-being that is predicted by these theories, the analyses discussed above show that (i) adults of childbearing age generally seem to expect that having a(nother) child will make them happier, with these beliefs being particularly strong among childless men and women in the primary ages of childbearing, and (ii) the expected happiness gains from children vary importantly depending on institutional contexts.

However, the experience of individuals after they enter parenthood and/or have an additional child can differ from the anticipated changes in well-being. While one would expect this to happen from time to time due to idiosyncratic influences on the satisfaction derived from parenting, this may also be the case for the parental experience on average—especially for parents having higher-order children.

All in all, the conclusion of the literature seems to be that the effects of children on parental happiness are weak, and if they exist, they are mostly associated with parenthood per se, rather than a particular number of children. And this matters for fertility trends: if becoming a parent provides a unique source of happiness, most individuals in low fertility countries are likely to continue to desire at least one child, providing a floor on how low fertility is likely to decline. But parental happiness gains from second and third children seem to be low and variable across contexts, suggesting that having more than one child will depend on individual and societal contexts “being right” for having children.

6. Social policies can raise fertility rates in low-fertility countries: Mostly a myth.

The benefit-cost ratios for policies to increase fertility in low-fertility settings —such as generous parental leave, child benefits, and related social programs—are not likely to be favorable. There is relatively weak empirical support for the effectiveness of many policy options that have been considered, despite their substantial private and/or social costs. A recent detailed analysis of the expansion of Norwegian maternal leave, for instance, concluded that the large increases in public spending on maternity leave required a considerable increase in taxes, at a cost to economic efficiency, with no measurable effects on children’s school outcomes, parental earnings, and parental participation in the labor market.

In contrast to the weak evidence for the expansion of maternal leave policies, there is some recent evidence that the expansion of publicly funded day care facilities has contributed to increases in fertility (or, at least, a slowing down of fertility decline). Increasing access to early child care is therefore a potentially promising option for policy-makers in high-income countries concerned about very low levels of fertility.

A similar conclusion was reached by a very comprehensive evaluation of family-related government programs in Germany, which spends about 200 billion Euros per year on family-related tax credits, child payments, subsidies for day care, etc. In many cases, the programs cannot be shown to have achieved their aims. A possible exception, consistent with other studies on this topic, is the expansion of high-quality day care for preschool children: It facilitated increased labor force participation among parents with small children, made important contributions to the human-capital formation of small children, and had modest effects towards increasing fertility, according to the evaluation. But it is unlikely that any policy can close the significant fertility gaps that exist across Western nations.

Hans-Peter Kohler is the Frederick J. Warren Professor of Demography at the University of Pennsylvania.