Highlights

- In every major Protestant group, and among Catholics, there are less than 100 prime-age, unmarried men per 100 prime-age, unmarried women. Post This

- What makes American churches bad places to meet a spouse is that American churches just don’t have many unmarried young people at all. Post This

- The dearth of men in church is considerably less severe, and considerably less mysterious, than it is made out to be. Post This

There is a crisis of absent men in American churches.

This is a widely accepted view. There are books on the topic, along with informative websites to help churches fix this problem, and there are occasionally surveys cited to demonstrate the severity. But much as Evangelical fears about widespread pornography usage probably overstate the reality of the problem, the dearth of men in church is considerably less severe, and considerably less mysterious, than it is made out to be. These facts may matter to religious leaders for a variety of reasons, but for family demographers, there is a very specific significance to gender imbalances. Religious communities often form semi-closed dating and marriage markets: people of a given faith often prefer to be coupled with people of the same faith. If there are large gender imbalances, with far more men or far more women, then young people may have difficulties forming families.

Using a variety of data sources, it’s possible to show which religious groups have the most severe gender imbalances. However, due to sample sizes and to keep this piece manageable in length, I focus just on Christian groups.

So, is it really the case that American churches have a deficit of men?

Data for Religious Demography

Gender imbalances might matter because they alter what options young people have for dating and marriage, especially in Christian communities where same-sex relationships are often prohibited.1 Thus, the relevant ratio is not just men to women, but young, unmarried men and women. And because many Christian religious traditions frown on divorce, I focus here on young men and women under the age of 50 who have never been married, or who are widowed.

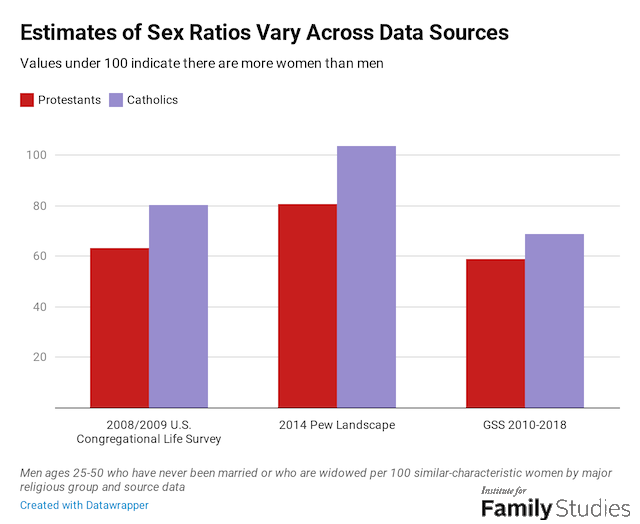

Across different surveys, there are very different estimates of sex ratios among this group. Consider the two largest religious groups in America, Protestants and Catholics. The graph below shows different estimates of how many prime-age, unmarried men self-identify with each religious group for every one-hundred similar women.

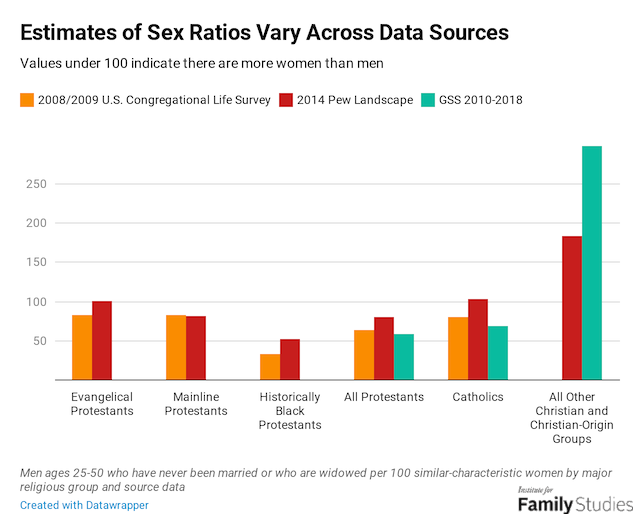

Measured sex ratios vary widely by source, as can be seen. But while the estimates vary in scale, different sources agree on relative ratios across different religious groups. Figure 2 compares the 2014 Pew Religious Landscape Survey (PRLS), the 2008/2009 USCLS, and the 2010-2018 General Social Surveys. While absolute values differ, the three sources basically agree on the order of groups. Historically Black Churches (HBCs) have the biggest deficit of prime-age unmarried males, while all sources agree that non-Protestant, non-Catholic Christian groups actually have more men than women! Among Catholics and Protestants, there is some disagreement, but the broad trends hold up.

Men at Church

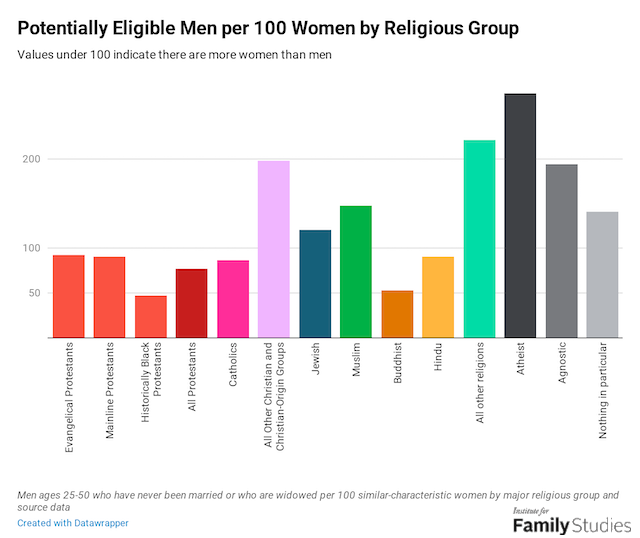

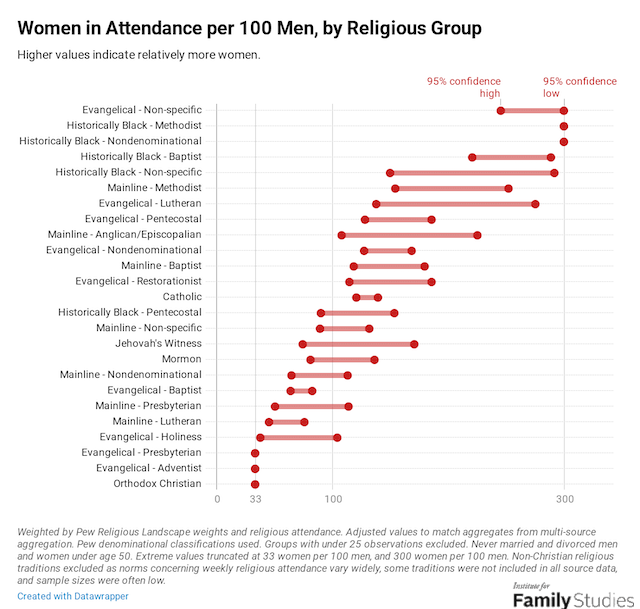

Using a combination of available sources, it’s possible to look at gender ratios in some detail.2 In every major Protestant group, and among Catholics, there are less than 100 prime-age, unmarried men per 100 prime-age, unmarried women. Among HBCs, the situation is especially severe: there are less than 50 men for every 100 women. Among “Evangelical” Protestants, which includes a variety of more conservative denominations, the imbalance is far less severe: there are about 93 men per 100 women. Finally, the most male-dominated groups are the catch-all group of smaller Christian bodies like the Orthodox and Christian-origin bodies, like Mormons, as well as the non-religious groupings, like atheists and agnostics.

If you google statistics on men in the church, the main number you will find is that 61% of the people in church on a Sunday are female. This figure comes from the USCLS. But when I restrict to prime-age, unmarried people, and supplement USCLS with large-scale randomized surveys, it turns out that it’s more like 52-57% of people who identify as Christian are female, which is considerably less severe.

But this is all based on self-identification. What we really want to know is not who claims to be of a certain faith, but rather who participates in the community of faith.

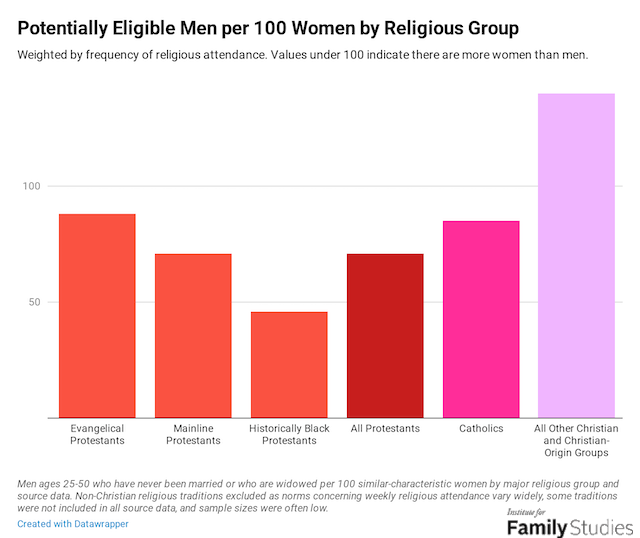

To assess this, we can weight each respondent in each survey by their reported religious attendance. This is a way to estimate what the gender balance of actual attendance may look like: a person who attends twice as frequently will count for twice as much, which makes sense, given that this person is exposed to the community, including its more irregular attendees, twice as frequently. Once we weight gender ratios by religious attendance, the gender ratios get more severe.

Men who identify with a given religion participate in religious community less frequently for most religious groups. Among the Christian groups with large enough samples to speak confidently, the largest sex-difference in religious participation can be seen in the Mainline Protestant churches. Among all self-identified Mainliners, there are 91 marriageable men for every 100 such women. But in terms of who actually shows up, the average Sunday service probably has more like 71 men per 100 women.

These might sound like decent odds for a dating market. But in fact, they are abysmally bad. Consider the case of a Mainline Protestant woman who has some desire to marry a Mainline Protestant man. The average Mainline church has about 80 attendees on a Sunday. Of those, about 11 are likely to be under 50, not married, and not divorced. Of those 11, six or seven are likely to be women; let's call it seven, as we stipulated that the scenario centers around a woman. That means there are seven eligible women and 4 eligible men.

Of course, it’s likely some of those men and women are already dating each other or people outside the community; and that’s not even considering the question of whether those four men are actually a good match in terms of what that woman wants in a partner. Even expanding this scenario to assume that same-denomination churches in a region are a single dating market, you can expand to five or 10 churches and still end up with a single-digit number of men who meet the basic demographic criteria and aren’t currently in a relationship with someone else.

This is not a functional dating market. So, it’s no wonder the share of Americans who meet their partner at church has plummeted from about 12% in 1940 to barely 4% today.

But in reality, for many religious people, “all Evangelical Protestants” aren’t the relevant dating pool. Religious young people often want to have a relationship with people of their same religious tradition. To assess this, I use PRLS’ “religious families,” which group together denominations of a similar historic tradition (Lutheran, Baptist, Anglican, etc.), while still separating groups of denominations by the Evangelical, Mainline, HBC, and other categories.

These patterns match those seen in the more aggregated groups: historically black churches have the largest gender imbalances. However, it is notable that my own religious tradition, evangelical Lutheran churches,3 is one of the most lopsided groups as well. Meanwhile, the mainline Lutheran church actually has relatively more men.

But, if instead we look at Presbyterians, the evangelical Presbyterian Church of America has a much more relatively male-biased population than the mainline Presbyterian Church of the United States of America.

In other words, gender ratios don’t seem to be closely related to doctrinal differences. Churches that ordain women or not, or those that are more conservative or more progressive, don’t seem to have systematically different gender ratios in their pews.

Religious Community, Religious Belief

But out of curiosity, I took an even closer look at the issue of a partner’s “eligibility” for a committed relationship. The PRLS data includes some more detailed questions about religious belief and practice. Normally, sociologists just look at a few headline variables like frequency of religious attendance. But for a devoutly religious person, many other factors matter too! For a person hoping to marry someone else of the same faith, it’s not just a question of religious attendance. Among Adventists, vegetarianism may be a very important shared commitment. Among Catholics, some of the single men and women may have taken vows of celibacy. And among Protestants, especially of the evangelical variety, a person’s regimen of prayer, Bible study, and church volunteering is a vital part of religious life.

For a relatively religiously devout person who wants to marry a similarly devout partner, what do their odds look like?

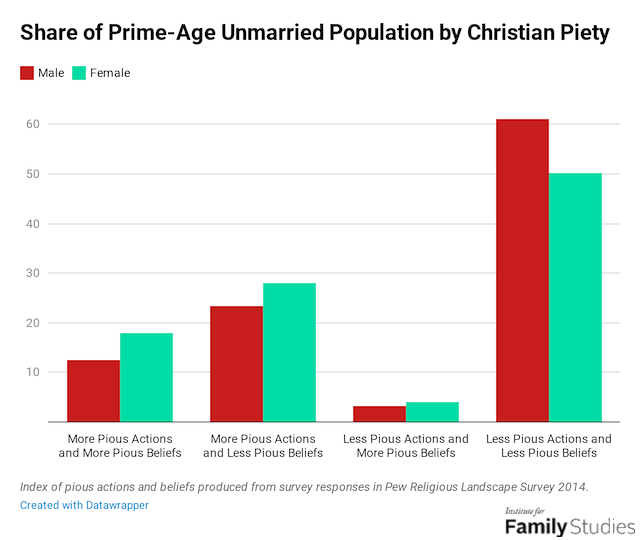

I used PRLS data to score every respondent on the degree to which they self-report pious activities like church attendance and prayer, and separately the extent to which they state agreement with simple Christian teachings, like the existence of a personal God, or the role of God in creating human life. There are subjective decisions involved in this scoring, but broadly speaking for a person to fall in the “more pious” category, they needed to be about one standard deviation above the society-wide average in terms of frequency or intensity of religious activities, or in terms of expressed agreement with Christian teachings. Figure 6 shows what share of the never-married or divorced population under age 50 population falls in each category, by gender.

Just 12% of prime-age unmarried men both believe basic Christian teachings and are meaningfully practicing Christian piety. The figure is about 18% for women. This means that for both men and women, majorities are not in any meaningful sense practicing or believing Christianity. This includes people of non-Christian faiths, people of no faith, and people who may identify as Christian, but who are extremely irregularly connected to a church and who also espouse few Christian beliefs.

And what’s the gender ratio among those more pious Christians? For every 100 eligible women, there are 85 eligible men. In other words, large shares of devout Christian women will have great difficulty finding a similarly, or even passably, devout Christian romantic partner.

Conclusion

It’s tempting to make this a story about changing cultural attitudes about gender, but that story is wrong. Women have been more religiously devout than men in Western society at least since the rise of Christianity; indeed by some metrics, the 19th-century church may have had an even bigger gender imbalance than today. Where there are the most severe gender imbalances today, like among Historically Black Churches, the cause is not mysterious: fatherlessness, drugs, and incarceration. Other denominations with severely imbalanced sex ratios likely have other specific reasons for their dearth of men. The point is that, on the one hand, some degree of sex imbalance in the church is quite normal and no threat to the vibrancy of Christian communities, and, on the other hand, a severe sex imbalance (worse than 90 men per women, for example) often has a concrete sociological origin, often outside the church.

So why does it seem so much harder to find a spouse in the church than in the past?

Revisiting the example Mainline Protestant dating market from above, it’s worth considering what really happened. It wasn’t actually the sex ratio that made dating hard for our hypothetical women. By the time we even considered the sex ratio, we’d already slimmed the market down from 80 participants to 11 just through basic demographics.

What makes American churches bad places to meet a spouse is that American churches just don’t have many unmarried young people at all. Finding a good spouse requires a considerable volume of options, which is why online dating and other digital options are so popular. They correctly recognize that finding a good match often requires sorting through a large number of bad matches. Churches are only useful places to meet a spouse if there are a lot of young people there.

Throughout history, people have usually met their romantic partners at whatever place gave young people opportunities to congregate. In some times and places, that has been churches. In some, it is schools. In others, bars or festivals. Today, it’s largely online and digitally.

But it might not have to be that way. Small, struggling churches could consolidate into larger bodies with a larger dating market, giving more young people incentives to participate. Research in my own denomination has found that young people catechized in large congregations are more likely to remain in the faith into adulthood versus similar young people catechized in smaller churches. Big congregations better communicate the vibrancy of church life through a high density of community activities.

Indeed, if churches combine together, or if they collaborate on frequent festivals and events (which are also the last remaining holdouts of religiosity in a super-secularized society like Japan), that creates greatly-expanded spot-markets for finding a partner, especially if the event is something fun and easy to invite friends to (like, for example, a Lutheran church hosting an Oktoberfest). In other words, the “dating market” for most religious groups, with the exception of HBCs and other severely imbalanced groups, is not mostly constrained by sex ratios. It’s mostly constrained by economies of scale.

1. Religious demography is greatly complicated by the fact that U.S. government surveys do not ask about religion. Thus, conventional demographic sources are of no use. Instead, large social surveys have to be used. The Pew Charitable Trusts have conducted the largest surveys on American religious life, with their most recent comprehensive religious survey conducted in 2014, with other group-specific surveys in 2011, 2012, 2015, and 2017. The General Social Survey (GSS) also includes questions about religion, making it useful for answering this question. To ensure a large enough sample size, I pool GSS data from 2010 to 2018. Finally, the U.S. Congregational Life Survey (USCLS) also conducts an enormous survey with tens of thousands of respondents; however, its sample is not truly random, and based instead on which congregations and parishioners are most willing to participate.

2. I combine estimates derived from all sources, weighted by the number of relevant cases. So, for example, across all sources I have about 6,900 never married or widowed Protestants ages 18 to 50. By pulling from a wide variety of sources, I am able to account for some of the idiosyncratic source-specific errors in given surveys and get a much bigger sample size. The resulting data gives probably the best currently-possible estimate of the gender balance in the “dating market” in different religious groups.

3. This category includes the Lutheran Church- Missouri Synod, the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod, and the Evangelical Lutheran Synod, but notthe Evangelical Lutheran Church of America.