Highlights

- In every country (without exception), more girls than boys aspired to a people-oriented occupation, and more boys than girls aspired to a things-oriented or STEM occupation. Post This

- We found that for every girl who aspired to enter a things-oriented STEM occupation, there were 5 boys. Again, the ratio was larger in gender-equal countries. Post This

- The sex differences in interest in people and things is not only found throughout the world today but stretches back at least a century. Post This

A quick Google search of news articles on gender differences in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) yielded 95,000 hits, and a similar Google Scholar search of academic articles yielded more than two million. These patterns reflect an almost obsessive focus among many politicians and gender activists on the fact that there are more men than women in certain STEM fields, especially engineering, computer science, and information technology. These disparities are an obsession because they deviate from the ideological belief that there should be gender equality (equal outcomes) in all domains that are socially influential and important.

In some people’s minds, this utopian state is being thwarted by outside forces that are suppressing girls’ and women’s engagement with these areas of study and occupations. Some believe that one such force is “stereotype threat,” whereby socially derived negative stereotypes (e.g., regarding women and mathematics) undermine girls’ and women’s performance in these areas,1 but that notion has been rejected by different research groups due to methodological and statistical problems.2 A focus on such external forces allows people to maintain the belief that gender equality in socially valued domains is just around the corner, given sufficient interventions to change these forces. At the same time, such a focus robs girls and women of personal agency and fails to consider that the interests, motivations, and strengths of girls and boys may differ for reasons that are not due to stereotypes, socialization, implicit bias, sexism, or a host of other factors.

If social factors, whatever they might be, are driving the sex differences in occupational interests and choices, then these differences should disappear or become smaller in societies that promote social, political, and occupational equality. In a prior study, we showed just the opposite.3 The sex differences in the proportion of women and men who pursue college degrees in things-oriented STEM (e.g., engineering, computer science) was larger in gender-equal countries, such as Finland and Norway, and smaller in less gender-equal countries, such as Algeria. In the latter countries, women appear to pursue STEM degrees for economic reasons rather than for personal interest. Whatever the reasons, larger sex differences in wealthy, gender-equal countries are common and include aspects of personality, psychopathology, self-esteem, and many physical traits (e.g., height).4

We recently completed a follow-up to our earlier study of gender-equality and sex differences in the pursuit of STEM degrees.5 Here, we analyzed the occupational aspirations of nearly half a million 15- and 16-year-olds across 80 developing and developed nations that participated in the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) of mathematics, science, and reading competencies. In this assessment, students were asked to answer the question, “What kind of job do you expect to have when you are about 30 years old?” which we termed occupational aspirations. PISA staff classified occupations using the International Standard Classification of Occupations.6 We then classified these as things-oriented, people-oriented, or other (i.e., neither clearly things- nor people-oriented), based on the well-documented sex differences in interest in things versus people.7

There are sex differences in occupational aspirations and choices that are universal; they are found across generations and across nations. The consistency of this pattern suggests fundamental sex differences in the types of activities, including occupations, that are attractive to girls and women and boys and men.

Things-oriented occupations are heavily focused on using or designing a tool or machinery. These include blue-collar and white-collar occupations, such as welding, civil engineering, or application programmer. People-oriented occupations are centered around interacting with clients, customers, or children. These include all teaching and instructor occupations as well as professions that involve helping patients (e.g., physician, nurse). Occupations that did not fit either of these categories, such as biologist, legislator, or accountant, were classified as "other." We also separately analyzed aspirations for entry into things-oriented STEM occupations (e.g., engineer).

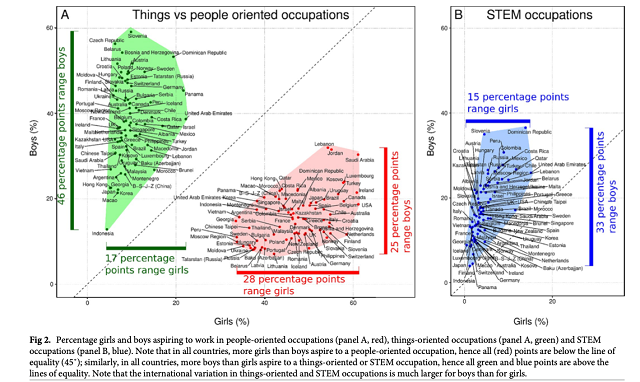

The figure below shows the percentage of girls and boys aspiring to work in people-oriented occupations (panel A, red), things-oriented occupations (panel A, green) and STEM occupations (panel B, blue). In every country (without exception), more girls than boys aspired to a people-oriented occupation, hence all (red) points are below the diagonal line, and more boys than girls aspired to a things-oriented or STEM occupation.

Across countries (median), there were about 4 boys for every girl aspiring to a things-oriented occupation, and about 3 girls for every boy aspiring to a people-oriented occupation. Both the things-oriented ratio and the people-oriented ratio were larger in wealthy, gender-equal countries, in keeping with our earlier gender equality paradox finding for STEM degrees. Indeed, we found that for every girl who aspired to enter a things-oriented STEM occupation, there were 5 boys. Again, the ratio was larger in gender-equal countries. As examples, there were 1.5 and 1.7 boys for every girl aspiring to a things-oriented STEM occupation in Morocco and the United Arabic Emirates, respectively, as compared to 4.5 and 4.8 boys to every girl in gender-equal Sweden and Norway.

These patterns mirror those found in a 1918 survey of almost 1,700 U.S. adolescents. That survey found that there were almost 12 boys to every girl with interests in occupations that involved working with engines (blue-collar and white-collar), and 12 girls to every boy interested in teaching.8 A similar study conducted about 15 years later revealed the same sex differences, that is, boys, in general, were more interested in occupations that involved working with things, and girls in occupations that involved working with people.9 In other words, the sex differences in interest in people and things is not only found throughout the world today, as we and others have found, but stretches back at least a century.

That said, we did find evidence for secular changes in girls’ occupational aspirations, especially girls from higher-income families. Adolescents from lower-income families had more sex-typical aspirations, often in blue-collar professions. Adolescents from higher-income families had more white-collar aspirations, including boys’ interest in things-oriented STEM fields. Many girls from these families were interested in professions that were neither things- nor people-oriented (e.g., accountant, manager). The latter findings are consistent with changes in women’s occupational choices from 1972 to 2010 in the U.S., where there was an increase in women working in professional occupations but there was not a shift to more engagement with blue-collar or white-collar things-oriented occupations.10

In all, there are sex differences in occupational aspirations and choices that are universal; they are found across generations and across nations. The consistency of this pattern suggests fundamental sex differences in the types of activities, including occupations, that are attractive to girls and women and boys and men.11 Nothing short of draconian social engineering will change these patterns to reach the utopian goal of gender equality in high-status male-typical occupations. Rather, social changes have resulted in more women entering professional occupations but not a shift toward interests in male-typical STEM (or blue-collar) occupations.

David C. Geary is a Curators’ Distinguished Professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences and Interdisciplinary Neuroscience at the University of Missouri. Gijsbert Stoet is Professor of Psychology at Essex University (UK).

Editor’s Note: This essay is based on findings from Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2022). Sex differences in adolescents’ occupational aspirations: Variation across time and place. PLoS ONE, 17, e0261438.

1. Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 4–28.

2. Stoet, G. & Geary, D.C. (2012). Can stereotype threat explain the gender gap in mathematics performance and achievement? Review of General Psychology, 16, 93-102. Flore, C.P. & Wicherts, J.M. Does stereotype threat influence performance of girls in stereotyped domains? A meta-analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 53, 25-44.

3. Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2018). The gender-equality paradox in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. Psychological Science, 29, 581-593.

4. Schmitt, D. P., Long, A. E., McPhearson, A., O'Brien, K., Remmert, B., & Shah, S. H. (2017). Personality and gender differences in global perspective. International Journal of Psychology, 52, 45-56.

5. Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (in press). Sex differences in adolescents’ occupational aspirations: Variation across time and place. PLoS ONE.

6. Bureau of Statistics, work unit of the Policy Integration Department. [cited 18 Apr 2021]. Available: https://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/intro.htm

7. Su, R., Rounds, J., & Armstrong, P. I. (2009). Men and things, women and people: a meta-analysis of sex differences in interests. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 859-884.

8. Miner, J. B. (1922). An aid to the analysis of vocational interests. The Journal of Educational Research, 5, 311-323.

9. Carter, H. D., & Strong, E. K., Jr. (1933). Sex differences in occupational interests of high school students. Personnel Journal, 12, 166–175.

10. Lippa, R. A., Preston, K., & Penner, J. (2014). Women's representation in 60 occupations from 1972 to 2010: More women in high-status jobs, few women in things-oriented jobs. PloS ONE, 9(5), e95960.

11. Geary, D. C. (2021). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences (third ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.