Highlights

- Young and middle-aged American men are less likely to be working now than at any time in U.S. history. Post This

- Childhood adversity is strongly related to current health, and adversity, parental marriage, and health are all strongly related to labor force participation. Post This

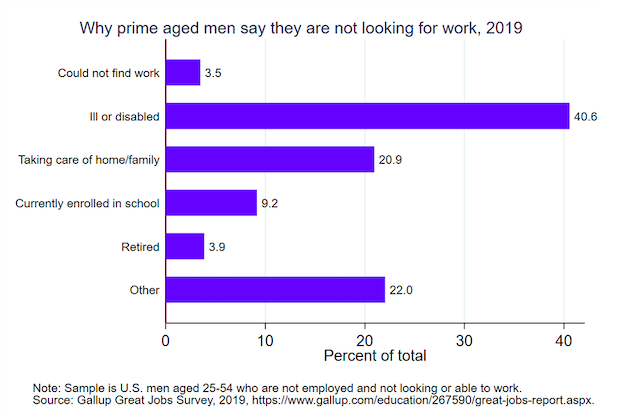

- Prime-aged men say that health is the most important reason they are not working. Post This

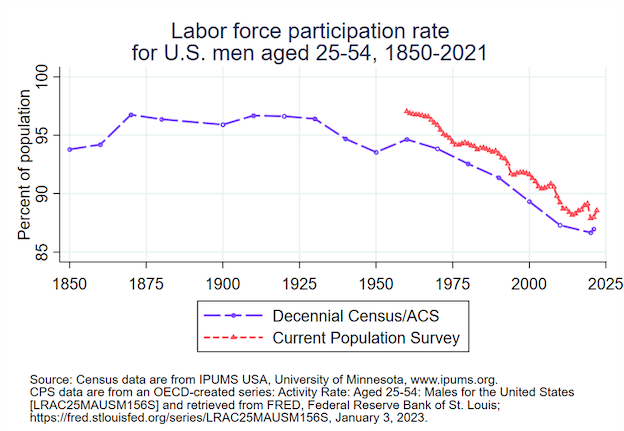

Young and middle-aged American men are less likely to be working now than at any time in U.S. history. The official labor force participation rate for prime-aged men fell from 97.1% in 1960 to 88.6% in 2022 (averaged through November), using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey. This decline can be put into deeper historical context using data from the decennial census, which shows a drop from 96.7% in 1910 to 93.5% in 1950, preceding the steeper subsequent fall (Figure 1) from 1960 to the present.

The trend has gotten a great deal of attention among policy scholars and academics, but the fundamental causes are often muddled. With a few exceptions, scholars have downplayed the important role of physical and mental health and ignored how rising stresses on familial life may be leading to health problems in adulthood. As I argue below, health is critical to understanding labor force participation, and family well-being is likely to be a core component.

Views From the Left

The conventional Democratic Party position has been that trade and technology have lowered demand for male labor disproportionately, making work less attractive, especially for men without a college degree. In 2016, the Obama Administration’s Council on Economic Advisors CEA issued a paper called “The Long-Term Decline in Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation.” They ruled out several factors, such as a rise in spousal earnings or access to government benefits, and they dismissed the idea that men were “choosing not to work for a given set of labor market conditions”, and instead blamed technology, automation, and globalization for reducing men’s attachment to work.

On the analytic side, the demand-side story weakens upon close inspection. First off, inflation-adjusted median wages for men have stagnated since the 1960s but not declined, as Scott Winship, amongst others, has noted. Second, if demand for low-skilled labor has fallen enough to push 8% of men out of the labor force, why are unemployment rates for these same men near historic lows? In other words, it is clear that men who look for work are finding it, which is hard to reconcile with a low-demand story. Job vacancies per working-age adults are hovering around an all-time high, and have been since around 2016, suggesting that demand for labor is extremely high. Most of these jobs do not require a college education. Finally, during the period of rising import competition and manufacturing job losses, current or former manufacturing workers were no more likely to drop out of the labor force than workers in other sectors, as my research has shown, and manufacturing establishments were less likely to lay off workers than other domestic sectors. While manufacturing has faded, construction, transportation, installation, and repair jobs still provide just as many jobs as a share of total employment as they did in the 1960s, as information technology and professional opportunities have opened up, coinciding with a huge increase in male college attainment.

Importantly, the Obama Administration CEA completely ignored health. They consider that rising access to disability payments may have contributed, but they dismiss this—rightly in my view—as having too small an effect. They do not consider the possibility that men may be out of work for health reasons but not receiving disability payments.

Views From the Right

One of the most influential scholars has been Nicholas Eberstadt, whose writing has done much to bring this issue to the public’s attention. In a 2020 summary of his work for National Affairs, Eberstadt disputes the conventional liberal story described above. He notes the steady drop in labor force participation that doesn’t correspond with trade or technology shocks.

Instead, Eberstadt emphasizes supply issues. His main argument is that family structure has sapped the impetus for many men to work. In 1965, roughly 85% of prime-aged men were married. That fell by roughly 30 percentage points by 2015. In recent years, there is roughly a 10 percentage-point gap in labor force participation between men who never married and those currently married. This large gap persists even within education groups—more evidence against the demand story.

Yet it is difficult to know whether marriage causes work and other measures of success, or whether success raises the probability of marriage, and which effect dominates. It is both well-documented and obvious that higher social status makes men, on average, more attractive marriage partners. Eberstadt and others—such as George Akerloff—would argue that marriage makes men work harder.

I investigated this using data from IPUMS CPS that tracks men over two-year periods. This allowed me to see what happens to work hours when men go from unmarried-to-married or not-having-a-child to having a child from 1978 to 2022. I limited the analysis to prime-aged men and controlled for age and year of survey collection. First, it is clear that married men, men with children, and men who rate their health better work longer hours—with the latter showing the strongest correlation by far. Yet when predicting the change in hours worked from one year to the next, getting married doesn’t have any effect, and having a child predicts a small negative effect (-54 hours for the year). Declining health status has a large effect (-188 hours for those losing 4 points on a 1-5 scale). This analysis is not definitive, and it may be that marriage or fatherhood creates significant motivation to work that would otherwise be lacking, as some scholars have concluded, but I find it hard to believe that this effect is large enough to explain the patterns shown in the figure above.

Additionally, both the Obama CEA and Eberstadt rightly mention high rates of incarceration as one cause of labor force decline. My analysis of Gallup data collected between 2019 and 2020 shows that nearly 9.7% of prime-aged men have been incarcerated. This estimate is close to those produced in the literature using prison population databases to measure the lifetime risk of incarceration. Those data show a large spike in incarceration rates during the “War on Drugs” in the 1990s and a gradual fall in more recent years. Importantly, I find that former incarceration status lowers the probability of being in the labor force by 7.6 percentage points from 2019 to 2020. Fortunately, lifetime incarceration risk fell by roughly 50% from 2004 to 2016. Falling incarceration rates since the early 2000s should have resulted in rising labor force participation for younger cohorts relative to older cohorts. That is not seen in the CPS data, suggesting that incarceration trends are not a dominant cause.

Health and Work

Another possibility is that some men are increasingly incapable of holding down a job because of declining mental or physical health. Anne Case and Angus Deaton famously showed that middle-aged non-Hispanic, White Americans have been experiencing declining health and rising risk of death, especially among those who did not attend college—who have also seen the largest decline in labor force participation. They found that chronic joint pain and sciatic pain were among the symptoms associated with rising morbidity in this population. Likewise, the late economist Alan Krueger found striking evidence that prime-aged men who are out of the labor force frequently report poor physical health, emotional distress, and pain. Indeed, he found that 44% were currently taking pain medication and discusses the role of opioids in hindering work.

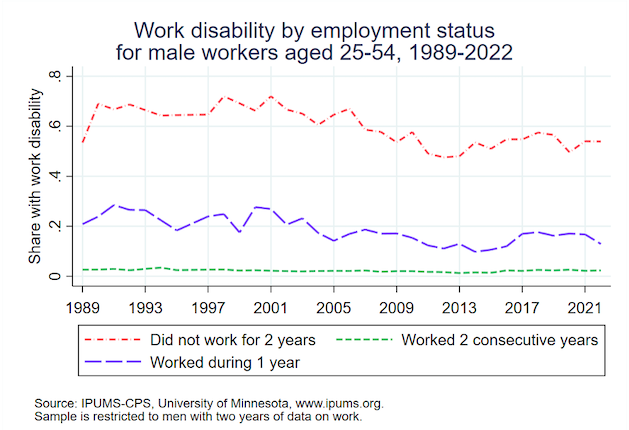

My analysis of the Current Population Survey distinguishes between men who did not work for two consecutive years, those who worked in at least one year, and those who worked in both years. The share of men who are out for two years has gone up from 3% to 9% from 1979 to 2021. There is a level and trend for those out for one of two years. In 2021, most men who are out of the labor force for two years report having a work disability (54%). For those out for only one year, 17% report a disability. By contrast, only 2% of those who worked both years report a disability.

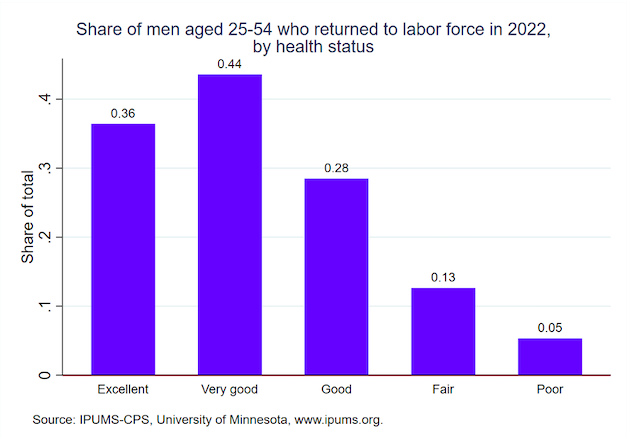

Accordingly, men who were out of the labor force in 2021 were 8 times more likely to return in 2022 if they were in excellent or very good health compared to those in poor health.

Other evidence comes from how men themselves understand why they are not working. Prime-aged men say that health is the most important reason they are not working. In a 2019 survey, Gallup asked men why they are not working. Among men who are prime-aged and out of the labor force, the most common reason given was “ill health or disability”: 41% gave this response, while 21% said “taking care of home or family,” and 22% cited some “other” reason not listed.

If health is key to labor force participation, and labor force participation is falling, one would expect health to be declining. Here, the evidence is not well established, but over the last 30 years, there is some data showing that prime-aged men are now more likely to be facing health-related impediments to work and other activities. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has conducted a nationwide survey since 1993 called the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). It collects detailed data on mental and physical health. One item reads: “During the past 30 days, for about how many days did poor physical or mental health keep you from doing your usual activities, such as self-care, work, or recreation?”

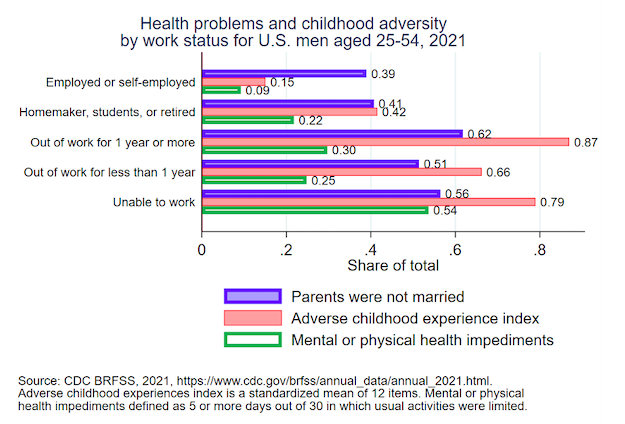

In 1993, 6% of men aged 25 to 54 said physical or mental health kept them from doing their usual activities for at least five days out of the past 30 days. By 2021, this share roughly doubled to 14% of prime-aged men. These ailments are clearly connected to labor force participation. Prime-aged men who are not working are 25 percentage points more likely to say physical or mental health problems limit their activities in 5 or more of the past 30 days, compared to those employed (34% versus 9%).

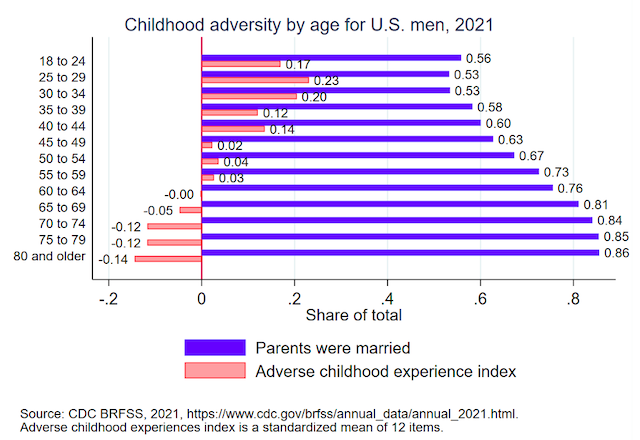

This raises the puzzling issue of why so many prime-aged men seem to be struggling with health issues. That complex issue is beyond the scope of this research brief, but one place to look for clues is their family of origin. It is well known that childhood trauma causes mental health problems into adulthood, as a recent meta-analysis found. The BRFSS recently started collecting data on adverse childhood experiences. These include 12 items about the respondents’ childhood household, such as whether they lived with someone who was depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal as a child, an alcoholic, or illegal drug user, incarcerated, abusive to the respondent or other household members, or sexually abusive. Two items asked whether an adult figure in the respondents’ childhood household made them feel safe and made sure their needs were met. Using 2021 data, I standardized each item and took the mean to create a childhood adversity index. A score of 0 is the average, and one is a standard deviation above the average, meaning the respondent experienced more adversity than about 84% of respondents.

Adults who grew up in married households had an adversity index that was 0.47 standard deviations lower than those who did not, and as has been widely noted, younger adults are less likely to have been raised by married parents. Along these lines, men born in the 1980s and 1990s had much higher adversity scores than those born in earlier years.

Childhood adversity is strongly related to current health, and adversity, parental marriage, and health are all strongly related to labor force participation. The causal effects cannot be precisely estimated from surveys such as these, but the associations suggest that labor force participation could be notably higher by preventing health problems or helping men cope with them. Consistent with this potential link, Carol Graham and Sergio Pinto have found that prime-aged men who are out of the labor force have particularly low subjective well-being and optimism.

Conclusion

The long-term decline in male labor force participation is a complex issue, and likely has many causes, some of which may be positive. Rising household incomes—brought about by economic innovation and the rising work and incomes of women—have surely allowed men to afford more time away from work than in past generations. Men in good health frequently rejoin the labor force after being out of it and contribute more to raising their children than in previous generations.

Yet there appear to be far more troubling causes. By some measures, prime-aged men have worse mental and physical health now than 30 years ago, consistent with concerns raised by Case and Deaton about rising deaths of despair. What is unambiguous is that prime-aged men who are out of the labor force suffer from poor mental or physical health at very high rates, and poor health is the most common reason they say they are not looking for work. Whether and to what extent health problems are rising, or why, is less clear, but children are less likely to grow up in two-parent families, and this is associated with a wide range of adverse experiences that, if untreated, can cause severe problems into adulthood. Concerns about trade, automation, and video games may be missing the most important factor at the root of contemporary men’s idleness: poor health.

Jonathan Rothwell is the Principal Economist at Gallup and a Non-resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution. He is author of the book A Republic of Equals: A Manifesto for a Just Society from Princeton University Press and can be found on twitter @jtrothwell.