Highlights

- "More affluent families spend more overall, but as income inequality has grown, more of their spending seems strategically invested in their children." Post This

- "The result is an 'arms race' of sorts, where higher-income families try to get ahead or just keep up by increasing their spending, but low-income kids are left behind." Post This

“Rising income inequality is reshaping parenting practices in the United States along class lines,” according to a recent report published in the journal, American Sociological Review. Authors Daniel Schneider, Orestes “Pat” Hastings, and Joe LaBriola used data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey and the American Heritage Time Use Survey, along with state-level data, to measure whether increasing income inequality is impacting the gap between how much money and time that upper-income and lower-income parents spend on their children. I asked report co-author, Dr. Pat Hastings, a sociologist at Colorado State University, about the findings and their implications for intergenerational mobility in the United States (this interview has been edited for clarity).

Alysse ElHage: Your recent report, “Income Inequality and Class Divides in Parental Investments,” found that the more income inequality there was at the state level, the more money upper-income parents spent on their children. How much more? Give us a sense of what the gap between upper- and lower-income parents looks like?

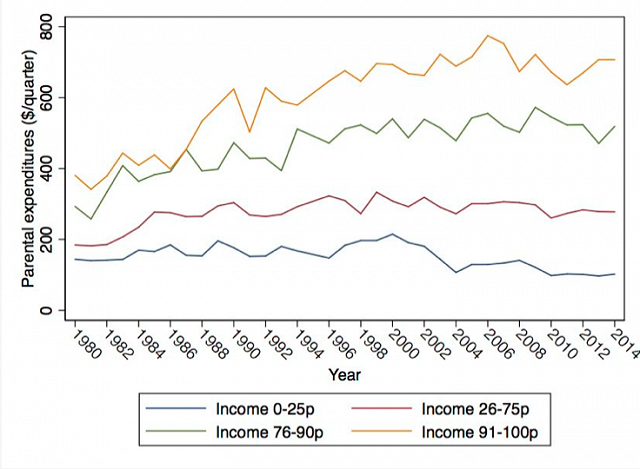

Pat Hastings: We looked at data from states between 1980 and 2014 and how that was associated with parental investments in lessons, extracurricular activities, school expenses, and childcare. In the highest income-inequality contexts, families whose incomes put them among the top 10% of earners spent more than four times what those in the bottom 25% spent on these things. Both income inequality and the gap in parental investments has been increasing over time. In 1980, parents in the top 10% spent about twice as much as those in the bottom 25% on these items. So, overall this gap has about doubled since 1980, but it grew more in the states that saw greater increases in income inequality.

Source: Schneider, Hastings, & LaBriola, "Income Inequality and Class Divides in Parental Investments," American Sociological Review, May 2018.

Alysse ElHage: According to the report, higher-income parents are targeting their money in specific ways that will ultimately boost their children’s chances at a better life. Talk more, if you will, about the kinds of things upper-income parents are investing in.

Pat Hastings: We didn’t try to comprehensively examine every expense related to parenting but instead focused on categories of spending that we think are important for kids’ future success: lessons, extracurricular activities, school expenses, and childcare. But we also separately examined some categories of spending that are less important to children’s development–such as kids’ furniture and clothing—which we called “consumption goods.” We found that rising income inequality was linked to widening class divides in parental investments but was not linked to spending on consumption goods. Of course, more affluent families spend more overall, but as income inequality has grown, more of their spending seems strategically invested in their children.

Alysse ElHage: It makes sense that rich parents would spend more on their kids when they have more money to spend, but what’s interesting about your study is that the bigger the gap between rich and poor in a state, the larger the gap in parental investment by household income. Why is this finding significant as we think about intergenerational mobility?

Pat Hastings: We think parental investments are important for children’s opportunities and success later in life in a number of ways. A lot of previous research has shown how early childhood investments—even before children are old enough to attend school—have long-term beneficial effects. Similarly, school-age children and youth who receive tutoring or participate in after-school and summer learning opportunities have real advantages with respect to academic achievement. And other extracurricular activities like sports and clubs help develop important non-cognitive skills and can even directly affect one’s competitiveness for selective universities and jobs.

This is significant because I think most Americans prefer a society with a relatively open structure where everyone a good chance of making it to the top if they work hard. While that’s obviously not impossible, our results show just how much harder that is for children growing up in low-income families. This is significant for middle- and upper-class families as well who are making ever larger financial investments in their kids.

Alysse ElHage: You also found that rising income inequality at the state level appears to change parental preferences. Explain this finding more for us and what it means for upward mobility for lower-income children.

Pat Hastings: We wanted to get beyond showing the relationship between income inequality and the class gap in parental investments and try to understand why this is the case. One possibility was that, because higher-income households have more income when inequality is higher, they just have more dollars to spend and end up spending it on their kids. Although this is fairly mechanical, it’s also very real and consequential.

The other possibility was that higher income inequality might really change how parents think and act when it comes to parenting and investing in children. If parents perceive of an increasingly winner-take-all society, then it becomes more important for them to give their children every advantage that they can. The result appears to be an “arms race” of sorts, where higher-income families try to get ahead or just keep up by increasing their spending, but low-income kids are left behind.

We find that both these things are happening, and each explains about half of the effect of income inequality on the widening class gaps in spending on children.

Alysse ElHage: Did your study find any differences in how much time upper- and lower-income parents invest in their children?

Pat Hastings: In addition to parents’ spending money on their children, we also looked at parents’ time with their children, which also has important long-term benefits for children. If higher-income parents were spending less time with their kids, then the class gaps in parental investments of money—particularly spending on childcare—might not really be so advantageous. Instead, this would have suggested that those parents were substituting their parenting time either to spend more time working (which may be part of the growing income inequality) or because their children were so busy in other activities.

But that is not the case. Since 1980, parents of all income groups have increased their time spent with children, and this doesn’t seem to be related to income inequality. So more affluent parents are making ever-larger financial investments in kids, while not reducing their time with their children.

Alysse ElHage: What are some things we can do to close this gap and help more lower-income kids achieve upward mobility?

Pat Hastings: Our research really only documents the trend, rather than pointing to a solution. I’d love to do more research on this, but I think existing research suggests several possible solutions, some of which are more realistic than others.

For example, it’s probably not very realistic to expect higher-income families to voluntarily tone down their spending, because – like the classic “prisoners dilemma” – there’s no reason for them to do it unless others do, too. Likewise, reducing income inequality itself would also help reduce this gap in parental investments, but this is very controversial and seems unlikely in the current political climate.

The most feasible answer is greater public and private investment in children from low-income families. Schooling itself has an equalizing effect, and all children can benefit from high-quality schooling. But there’s a role for private spending too. In my city, for example, a local foundation recently provided youth-enrichment grants to low-income families to make sports leagues and summer camps more affordable for their children. Community organizations, philanthropic foundations, church programs, volunteer mentoring programs, and the like can provide real benefits for low-income children.

Ultimately, there’s probably no single right answer, but a combination of these things—which range from national- and state-level policy-making to local involvement—can help give lower-income kids better opportunities to succeed.

Orestes Pat Hastings is a sociologist at Colorado State University whose research explores how the features of people’s social and economic contexts influence their decisions, behaviors, and attitudes.