Highlights

What protects marriages from difficult events and circumstances? A relatively straightforward question, but one whose answer I think most marital researchers (myself included) would acknowledge remains unresolved. And this lingering question is not merely an academic conundrum, but significantly affects the resources available to professionals and couples seeking to strengthen marital unions.

In light of this, my colleagues and I recently conducted two studies in which we investigated the protective effect of two different aspects of marriage that, to date, have received little empirical attention. Results from both studies were promising and suggest potentially untapped means of promoting marital quality.

Study 1

In the first study,1 we focused on couple social integration—the degree of connectedness a couple has with their social context. Decades of studies have documented the benefits of social integration for individuals’ well-being. Yet does this effect extend to marriages? Employing a measure developed by Scott Stanley and Howard Markman, we surveyed 492 married individuals to investigate the benefits to marital happiness from spouses’ appraisals that, as a couple, they are connected to other people and their community.

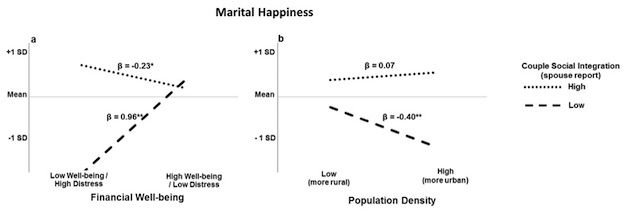

Results indicated that couple social integration was indeed associated with greater marital happiness, and this effect was particularly evident for couples with high financial distress and for couples living in more urban areas. In fact, as shown in Figure 1, financial distress was associated with a low level of marital happiness only for marriages in which spouses reported low levels of couple social integration; at high levels of couple social integration, levels of marital happiness did not suffer even with high levels of financial distress. Similarly, levels of marital happiness declined as local population density increased, but only among couples with low levels of couple social integration; levels of marital happiness were unaffected by population density among spouses reporting high levels of couple social integration.

Figure 1: Marital happiness as a function of (a) financial well-being and couple social integration and (b) population density and couple social integration

So, what do we make of this? Here are three immediate observations.

First, in thinking about couples and their social context, we should devote greater attention to how aspects of couples’ social environment can promote (rather than undermine) marital quality. Although the negative spillover effects from stressors such as financial strain are well-documented, results from this study highlight one means by which the social context may actually protect marital quality from hardship.

Second, individuals working with couples can help their clients think about ways to not only improve their interactions together, but also bolster their interactions with their community. Being involved, supported, and engaged with others—as a couple, and not just individually—appears to allow couples to strengthen their relationship and protect it against factors that they may be less able to influence, such as finances and where they live.

We should devote greater attention to how aspects of couples’ social environment can promote, rather than undermine, marital quality.

Thirdly and more broadly, books such as Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone and Alone Together (by Paul Amato and colleagues) have highlighted the formidable declines in social integration among American individuals and couples in the last half century. Communal ties and involvement are weakening across society, and the private sphere is, in a sense, becoming ever more private. In light of the benefits of social integration documented here and elsewhere, this decline suggests couples may be losing a resource that protects their marital happiness. Ensuring social integration among married couples, therefore, may require more explicit attention and effort.

Study 2

In the second study,2 we examined the effects of felt spousal gratitude—spouses’ sense of feeling appreciated, acknowledged, and valued by their partner. Multiple recent studies have touted the benefits of being grateful for your partner; such gratitude is linked to higher satisfaction, greater stability, and a more communal orientation in relationships. Yet we wanted to know: What are the results of feeling gratitude from your partner? In particular, we investigated its direct effect on aspects of marital quality as well as its ability to interrupt the negative sequence of events linking financial distress, negative communication (i.e., demand/withdraw interaction patterns), and lower marital quality.

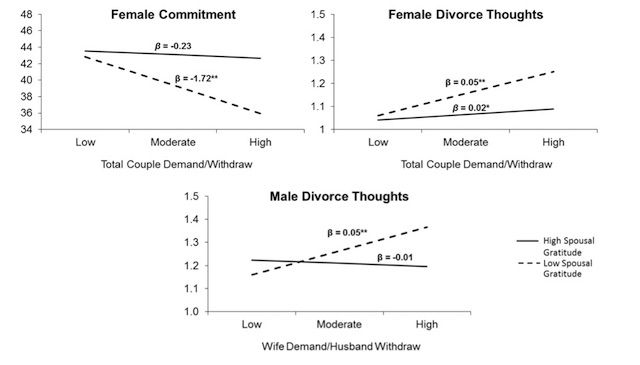

The results were clear. Individuals who felt more gratitude from their partners reported higher marital happiness, more commitment, and (among wives only) fewer thoughts of divorce. Moreover, spousal gratitude countered the negative effects of demand/withdraw interaction on indicators of marital stability (see Figure 2). In each instance, increasing levels of demand/withdraw were associated with greater instability (i.e., less commitment, more thoughts of divorce), but only among individuals who felt low levels of gratitude from their spouses. Those high in felt spousal gratitude did not report greater risk for marital instability, even with high levels of demand/withdraw interactions.

Figure 2: Spouses’ marital quality indicators as a function of demand/withdraw communication and spouses’ expression of gratitude

What do the findings from this second study mean? Three additional observations:

First, even couples who are not great at handling conflict can find other practical ways to strengthen their marriage, like doing and saying things to make sure their partner feels appreciated. Not every couple is going to be stellar at communication during conflict, but making a habit of saying “thank you” regularly and demonstrating appreciation by other means may be achievable for nearly all couples.

Second, as any married person can attest, a lot of marriage is comprised of mundane matters: running errands, cleaning dishes, getting kids ready for school. Gratitude (or lack thereof) may play a key role in how the multitudes of simple events that comprise a marriage eventually come to shape the bigger picture of marital satisfaction and stability. Thinking through the fundamental dynamics that positively or negatively shape people’s everyday experience of marriage—and how to effectively intervene in them—remains an important question for couples, therapists, and researchers.

Third, negative communication patterns appear to be less costly to marital stability when spousal gratitude is strong. In this way, gratitude may provide what some marital researchers have described as a “Teflon” effect.3 Gratitude, in essence, can envelop a couple and prevent negative behaviors and emotions from “sticking” to them and negatively altering their thoughts and behaviors toward their spouse.

Summary

Couple social integration and felt spousal gratitude: Two significant, yet potentially underemphasized (or at least under-investigated), marital processes that help couples navigate the strains of married life. Importantly, both of these processes also seem malleable to intervention, and capable of being changed by couples themselves. The more we are able to help couples strengthen aspects of their relationship that they can control—such as connecting with their community and making sure each partner feels appreciated—the more we can help them overcome the difficult circumstances that are beyond their control.

Allen W. Barton is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Georgia’s Center for Family Research. Much of his research focuses on family-centered prevention science, including the prevention of marital distress and divorce. He is the founder of LiveYourVows, a movement that seeks to help ordinary couples in ordinary marriages do something extraordinary—live your vows (Twitter; Instagram; Facebook).

1. Barton, A. W., Futris, T. G., & Nielsen, R. B. (2014). With a little help from our friends: Couple social integration in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 986-991. doi: 10.1037/fam0000038.

2. Barton, A. W., Futris, T. G., & Nielsen, R. B. (2015). Linking financial distress to marital quality: The intermediary roles of demand/withdraw and spousal gratitude expressions. Personal Relationships, 22(3), 536-549. doi: 10.1111/pere.12094.

3. Bradbury, T. N., & Karney, B. R. (2004). Understanding and altering the longitudinal course of marriage. Journal of Marriage & Family, 66(4), 862-879. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00059.x