Highlights

- While schools and mass media must take some responsibility, my analysis of public-use data from the Department of Education suggests that the development of political awareness among young people starts in the family. Post This

- Parents may also nurture political awareness in their offspring through their choice of the schools their children attend and the courses they encourage them to take. Post This

- Students earned higher scores on the political knowledge quiz if they talked with their mother or father frequently about national issues and current events. Post This

How do politicians get away with telling lies about their accomplishments or blatantly exaggerating the effectiveness of government programs? They do so because many members of the public, young and old, are not very knowledgeable about national issues. In a nationwide study, the Department of Education found that a typical high school student scored only 33% on a short quiz covering basic facts about the U.S. government and politics, such as the name of the current Vice President or what the first 10 amendments to the Constitution are called. Their elders didn’t do much better: a typical American adult scored only 53% on the same quiz.1

In 2018, a continuing monitoring program called, “NAEP,” or “The Nation’s Report Card,” found that more 8th Grade students scored “below basic” in civic awareness (27%) than were deemed “proficient” in their knowledge of government (24%). The rest (49%) had only a minimal, “basic” understanding. Furthermore, the state of civic knowledge of American students has not improved over the last two decades.2

Who is to blame for this state of affairs? Many commentators are quick to accuse schools, while others point their fingers at television and radio broadcasters for failing to inform their audiences about the basic facts and processes of our political life. Sociologist John Robinson of the University of Maryland contrasts mass media reporting on government and politics, which deals mostly in disconnected, “breaking news” coverage of electoral races and governmental scandals, with TV weather reporting, where the atmospheric processes behind tomorrow’s forecasts are laid out in graphic detail on a daily basis.3

While schools and mass media must take some responsibility, my analysis of public-use data from the Department of Education suggests that the development of political awareness among young people starts in the family. High school students’ performance on the political knowledge quiz is directly related to the educational attainment and family income of their parents and varies with family structure and across racial and ethnic groups. Similar relationships apply to 8th graders’ performance on the NAEP civics assessment.

Like Parents, Like Child

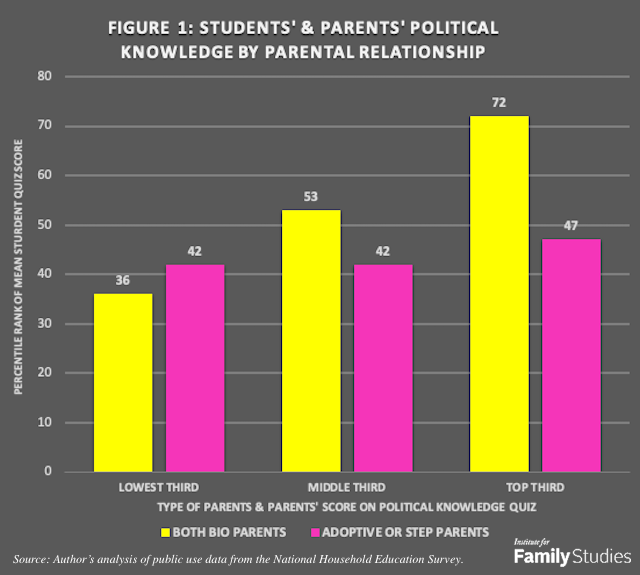

One of the strongest predictors of how much a child knows about politics and government is how much his or her parents know. As the NCES political quiz was administered to a child and an adult in the same households, I was able to relate the student’s score to that of his or her father or mother. (Alternate versions of the quiz were used when two were given in the same family.) When the parent scored in the bottom third of the adult distribution, the student’s score averaged at the 33rd percentile of the youth distribution. And when the parent scored in the top third, the student’s score averaged at the 67th percentile. When the parent’s score fell in the middle third, the student’s score was at the 48th percentile, on average.4

Adjusting the parent score-child score relationship for background factors, like parent education level, family income, and race, weakened the correlation somewhat.5 But the correlation remained significant, both practically and statistically.

Interestingly, the relationship between parent score and child score was stronger when parent and child were biologically related than when the parent was an adoptive parent or stepparent who was genetically unrelated to the child6 (see Figure One). Not surprisingly, this suggests that political knowledge is related, in part, to general intelligence.7

Parent-Child Communication

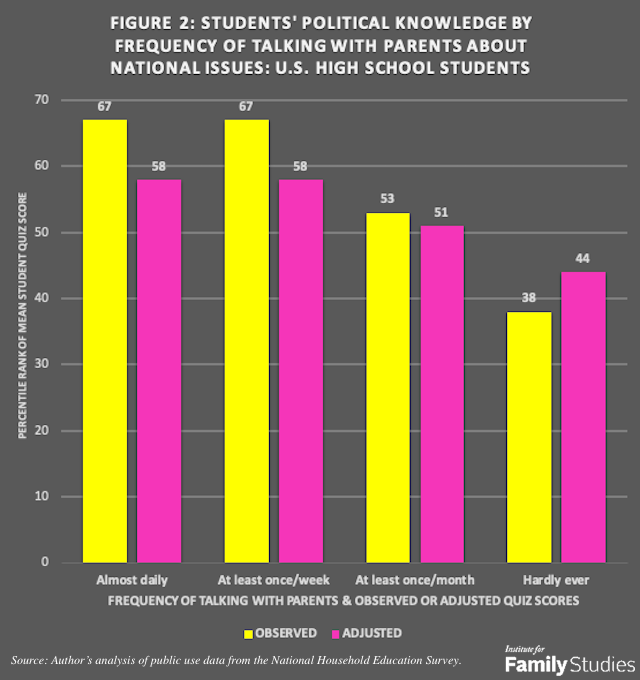

Students earned higher scores on the political knowledge quiz if they talked with their mother or father frequently about national issues and current events. Regrettably, only 5% of students reported having such conversations “almost daily,” whereas 47% “hardly ever” did.8 As shown in Figure Two, those who reported having such conversations almost every day or at least once a week scored at the 67th percentile, whereas those who hardly ever conversed about issues scored at the 38th percentile. Adjusting for family background weakened the relationship, as shown in the figure as well, but it remained significant.

Media Use

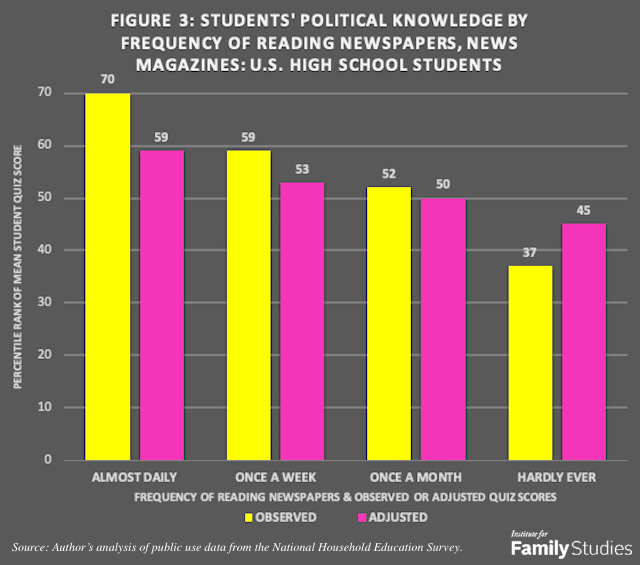

Families that subscribe to newspapers or news magazines tend to have students who are more knowledgeable about government and national politics. Yet only 9% of high school students reported reading newspapers on a daily basis, whereas 43% hardly ever did.9 Students who reported reading about national news in newspapers or news magazines almost every day scored at the 70th percentile on the political knowledge quiz, whereas those who hardly ever did such reading scored at the 37th percentile. Those who read about once a week or once a month had intermediate scores, as shown in Figure Three. Adjusting for family background reduced score differences, but the relationship remained linear and significant. By contrast, the regularity with which students reported watching national news on television or listening to news on radio was not significantly related to their political awareness score.10

Type of School Student Attends

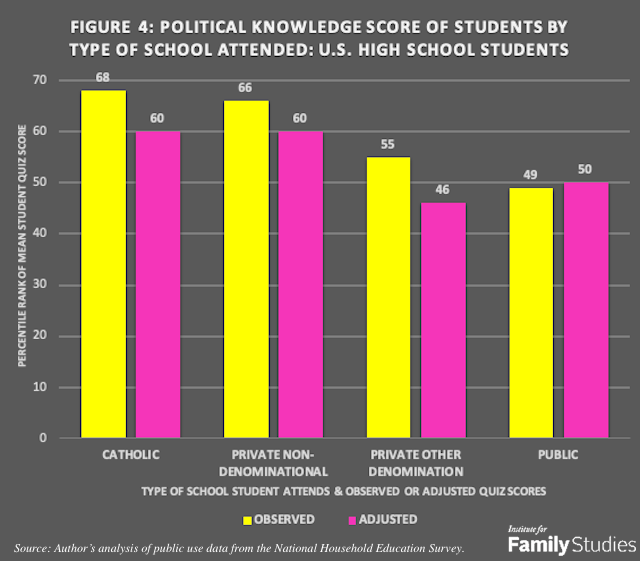

Parents may also nurture political awareness in their offspring through their choice of the schools their children attend and the courses they encourage them to take. Students who attended Catholic private schools scored at the 68th percentile on the political knowledge quiz, on average, and those attending non-denominational private schools scored at the 66th percentile.11 Both were significantly higher than the mean score for students attending public schools, which ranked at the 49th percentile. Students attending private schools affiliated with religions other than Catholic had an average score at the 55th percentile. This was not significantly higher than the public-school mean.

Differences between school types were reduced after adjusting for family background factors, as shown in Figure Four. The adjusted scores for students in Catholic schools and non-denominational private schools remained significantly higher than the average score for public school students.

Differences in civic knowledge across school types have also been found in the NAEP civics assessments. In 2018, 41% of 8th Graders in Catholic private schools were found to be proficient or advanced in their civics knowledge and skills, compared to only 22% in non-charter public schools. Students in public charter schools did slightly better (26% proficient or advanced). Conversely, the proportions of students whose civics knowledge was below the basic level was only 9% in Catholic schools, compared to 23% in charter schools and 29% in regular public schools.

Type of Courses Student Takes

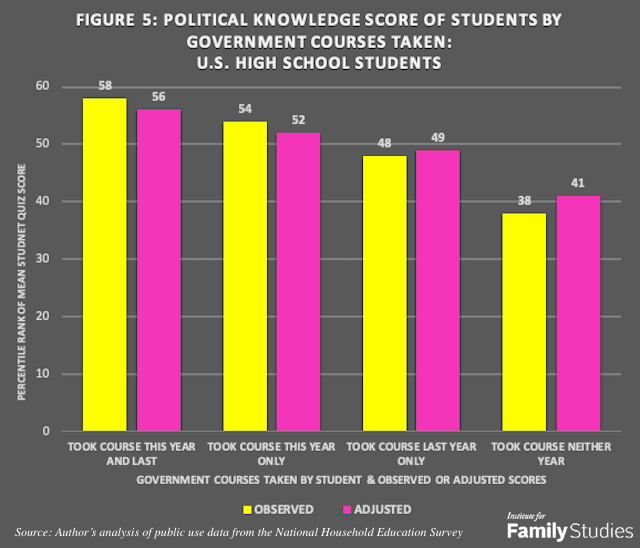

High school students who have taken courses in government or civics tend to have greater political awareness than those who have not had such courses. Students who were taking such a course in the current school year scored at the 54th percentile on the political knowledge quiz, while those who took such a course in the previous year as well scored at the 58th percentile.12 Both groups had significantly higher scores than students who took the course in the previous year only (48th percentile) or had not taken one either year (38th percentile). The relationship was weakened but remained significant after adjusting for school type and family background factors, as shown in Figure 5.

Toward A More Informed Electorate

There is consensus among political scientists and social commentators that a democracy cannot function well without an informed electorate. The findings presented in this brief, plus evidence from many other polls and studies, indicate that much of the American electorate is far from well-informed about vital public issues or how our political system operates. Nor do we seem to be making progress toward ensuring that future generations of citizens will be more politically aware than current ones, despite generally rising levels of educational attainment.

Although individual families cannot change this situation in a major way, parents can take steps to help ensure that their own children develop into knowledgeable, involved citizens. Some of these steps are the following, each supported by results described above:

- Staying informed about national and local issues themselves;

- Subscribing to newspapers or news magazines, and reading them regularly;

- Encouraging one’s children to do the same, when they are capable of it;

- Talking with them about current issues, political events and leaders;

- Sending them to schools with rigorous courses in government or civics and seeing to it that their children take such courses.

While taking these steps, parents can also help their children understand that other persons may have different political perspectives, that those with differing points of view should be respected, and that open discussion and debate of opposing viewpoints is not something to be feared or shunned, but is, instead, central to the workings of a healthy democratic society.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.

1. Author’s analysis of public use data from the National Household Education Survey. See also: Mary Jo Nolin and Chris Chapman. (1997). Adult Civic Involvement in the United States. NCES 97-906. U.S. Department of Education: National Center for Education Statistics.

2. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). (2019) 2018 Civics Grade 8 Assessment Report Card: Summary Data Tables. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

3. John P. Robinson, personal communication.

4. The correlation between parent and child scores was r = .39, N = 4,275, p < .0001.

5. Quiz scores adjusted by means of multiple regression analysis, setting covariates at their overall mean values for the sample. After adjustment, parent scoring in the lowest third had children who scored at the 41st percentile, on average, whereas parents scoring in the highest third had children who scored at the 60th percentile.

6. The correlation between parent and child scores was r = .38 when the child lived with both birth parents (N = 2,514, p < .0001), whereas the correlation was only r = .09 (N = 205, p = .21) when the child lived with adoptive or step parents, and an adoptive or step parent was the adult in the household who took the political knowledge quiz.

7. Ian J. Deary. (2001). Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction. Chapters 4 & 7. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

8. In addition, 22% of students reported that they talked with parents about national about once a week and 26%, about once a month.

9. In addition, 29% of students reported that they read newspapers or news magazines about once a week and 19%, about once a month.

10. Forty percent of students reported that they watched news on television or listened to it on radio almost every day; 31% did so at least once a week; 12%, about once a month; and 17%, hardly ever.

11. 5% of students attended Catholic private schools; 2% attended non-denominational private schools; 2% attended private schools affiliated with a religious denomination other than Catholic; 91% attended public schools.

12. 29% of students took courses in government in both the current and previous school year; 23% were taking such a course in the current school year only; 18% took such a course last year only; and 30% did not take such a course in either year.