Highlights

- Decline in time with friends may explain why parenting feels so exhausting to so many of us. In America, the playdate is dying. Post This

- Americans spend more time caring for their pets than for elders. Post This

- Mothers are not spending more time with kids than in the past, but dads are, especially unmarried dads who live with children. Post This

You may have heard about the rise in intensive parenting, the idea that parents are spending more time on “parenting” than ever before. And it’s true: by many measures, there has been a rise in “helicopter parenting,” and parents nowadays do seem more preoccupied with the work of raising children than parents of the past. But is it really the case that parents are spending more actual time on kids than in the past? Unfortunately, data on time use is low quality over long-time horizons, but the best evidence suggests that on the whole, there actually has not been much increase in how much time parents spend with their kids. What has changed, however, is what parents do with that time.

Time Use in the Long Run

One popular study, which has been cited widely, claims that parents are spending more time with kids than ever before. It relies on non-standardized time use data across many countries back to 1960, and specifically measures “child care.” In this case, exact definitions matter: “child care” means time parents said they were actively watching or interacting with their children. The data source includes surveys that aren’t strictly comparable and use different definitions of child care time, but even so, it does seem to suggest people are spending more time focused on their kids.

But think for a moment about parenting and time use. Suppose a parent is making dinner while their child is playing with Legos on the floor. The parent is obviously present with the child; but in another important sense, the parent’s actual activity is “cooking.” Or consider a parent who goes to the grocery store and brings along a child—is that child care? The answer is that nobody really knows. Modern time use surveys allow parents to report “secondary care activities,” and even those don’t capture the full extent of child-watching activities. Many time use studies don’t track the mere presence of children, but some do. For example, whereas the study above claims that Italian mothers added about an hour of hands-on-parenting a day between 2000 and 2010, time use data from IPUMS MTUS (a standardized international repository of time use data) shows that Italian mothers’ time-with-kids rose only 15 minutes in that time period. On the other hand, whereas the paper above suggests that French mothers spent about 10 minutes less per day on child care between 1985 and 2010, in reality, their time spent with children rose by about 15 minutes per day.

Thus, there doesn’t seem to be a close correlation between supposed increases in “child care” time and time parents spend “with kids.” A graph of all of this is messy and confusing because very few countries have multiple years of data for time with children. But one country has had continuous, reliable collection of this data for two decades now: the United States.

American Parenting is Stable

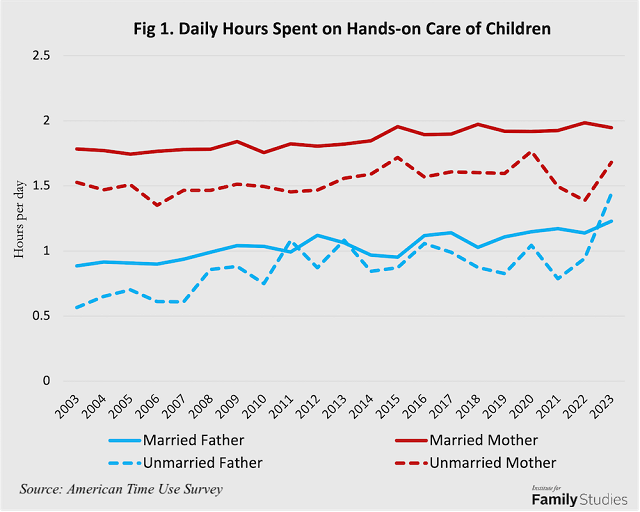

The American Time Use Survey (ATUS) has collected detailed data on child care and time with kids from 2003 to 2023. Figure 1 below shows results from that survey for how many hours per day men and women with children in the home report spending in hands-on care or interactions with children. Note that for unmarried parents, this would refer exclusively to those who have coresident children for whom they are a biological, adoptive, or step-parent. Parents without a child in the home with them are excluded from this calculation, and they have much lower levels of involvement with their children, on average.

Married moms spend about 2 hours a day on child care. This is up from 1.8 hours a day in 2003, consistent with the idea that parenting is getting more demanding. For unmarried moms, there’s been a much less consistent increase. Likewise, for married dads with a child at home, child care time has risen from 0.9 hours a day to 1.2 hours a day. For unmarried dads with a child at home, estimates are much more volatile, but have risen from about 0.6 hours per day to between 0.9 and 1.5 today. Here, it’s key to remember that this sample is only of unmarried men who have a child in the home. That child may or may not be their biological child, and non-coresident parents are not included in this calculation at all. Doubtless, the large numbers of fathers and mothers who do not reside with their children have very low time use on child care on average, but they cannot be identified in ATUS.

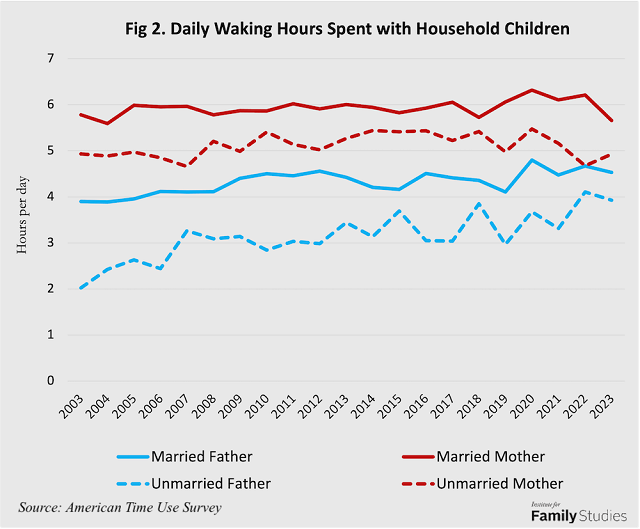

Thus, parents of all stripes are doing more child care than in the past. But are they spending more time with kids? Figure 2 below shows the number of waking hours spent with children by parents.

Married moms in 2003 spent about 5.8 hours a day with their children in some capacity—which is about the same as they reported in 2023. Likewise, unmarried moms in 2003 reported about 5 hours a day of time with kids, the same value reported by unmarried moms in 2023. For women, then, there’s been zero increase in hours spent with children.

For married dads, time spent with kids has risen from about 4 hours a day to about 4.5 hours a day, and for unmarried dads it has risen from about 2 hours to about 4 hours a day, a very large increase, but probably reflective of the very select sample of unmarried coresidential dads.

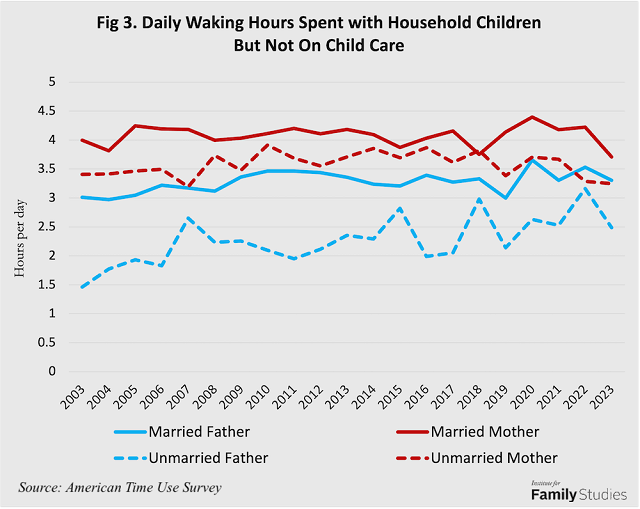

Thus, mothers are not spending more time with kids than in the past, but dads are, especially unmarried dads who live with children. This is overwhelmingly time spent not directly on child care, as shown in Figure 3 below. For example, if a parent’s main activity was “grocery shopping” or “cooking a meal” or “weeding the garden” and they just happened to be doing the activity with kids, these would be time “with kids” but “not on child care.” For moms, non-care time with kids has actually declined a bit in recent years; but for dads, rising non-care time accounts for virtually 100% of the increase in time spent with kids. Increasingly, dads are just bringing their kids along for work, or chores, or errands, or social activities, much as many moms have always done.

Thus, virtually the entire increase in “parenting time” comes from low-intensity supervision by dads. On the other hand, moms have shifted away from low-intensity parenting towards more hands-on, intensive parenting.

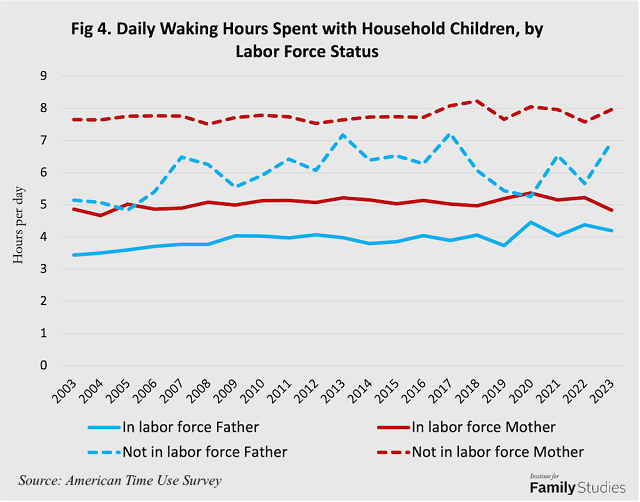

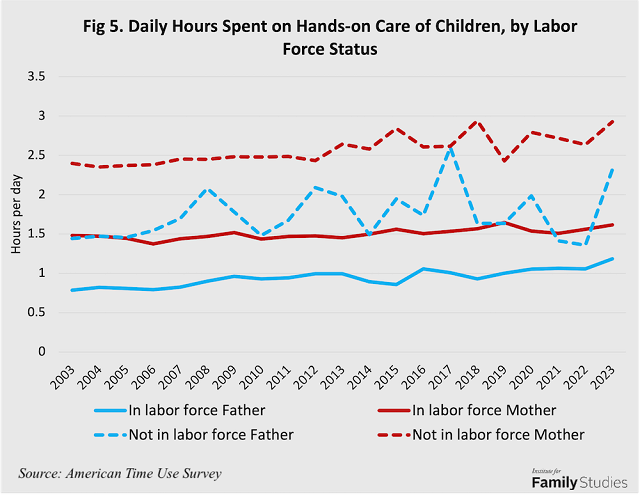

Obviously, jobs are the major competitor for parents’ time, so it’s worthwhile to break out the data by labor force status. Parents who aren’t employed or looking for work spend much more time with their children, as Figure 4 below shows. But again, there’s been virtually no increase for either working or non-working moms: the entire increase in parenting time is driven by dads.

Thus, to the extent the time demands of parenting have risen, these rising demands have fallen mostly on dads, though men still do quite a bit less care of children than women, even when they are stay-at-home-dads.

But this finding—of little overall change in demands on parental time—seems hard to square with popular perceptions of care duties. Parents today routinely testify to feeling swamped by all their children’s activities and feeling pressured to do more intense parenting. So what’s the story here?

Several changes in our parenting culture may explain why parenting seems more intense despite not actually taking much more time.

Other Care Duties

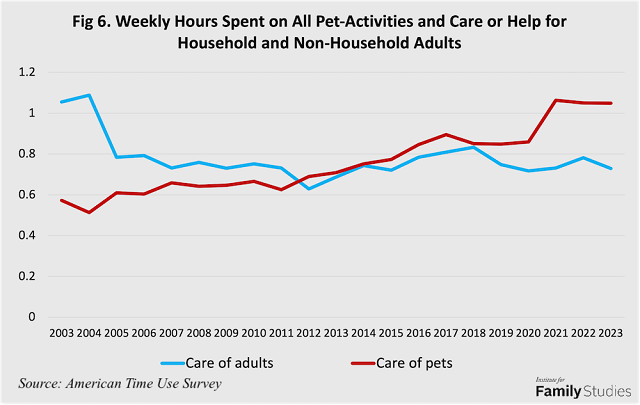

Even as parents are not spending much more time on their kids, they are spending more time on other things. Two other categories of care work stand out as especially noteworthy: care of pets and other adults (especially elders). As our society ages, it would make sense to find a growing burden of adult care. But this is not what ATUS finds: there’s been no major change in time spent on the care of other adults since 2005 or so.

On the other hand, time spent on care of pets has risen persistently. Whereas in 2003, Americans spent an average of about half an hour a week on their pets, by 2021-2023, they were spending over an hour a week. That means, Americans spend more time caring for their pets than for elders.

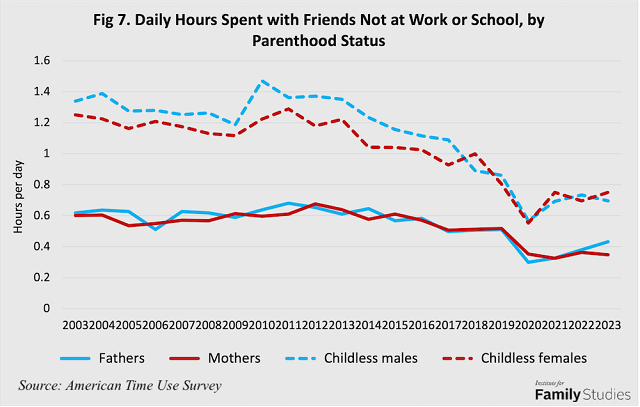

It’s likely other kinds of perceived duties and responsibilities have expanded as well, causing Americans to feel more crimped for time—but the simple reality is that when it comes to their care duties, the story that Americans are more overwhelmed than in the past is just wrong. Far from burdened by innumerable relationships, the rise in the care of pets is very much an exception in a general landscape of decreasing time spent on relationships of all sorts. Figure 7 below shows time spent with friends: it is down by 30-50% since the early 2000s. For nonparents, time with friends in 2023 was arguably near where you might expect from a pre-COVID trendline. But for parents (and especially moms), social time seems not to have recovered as robustly after COVID.

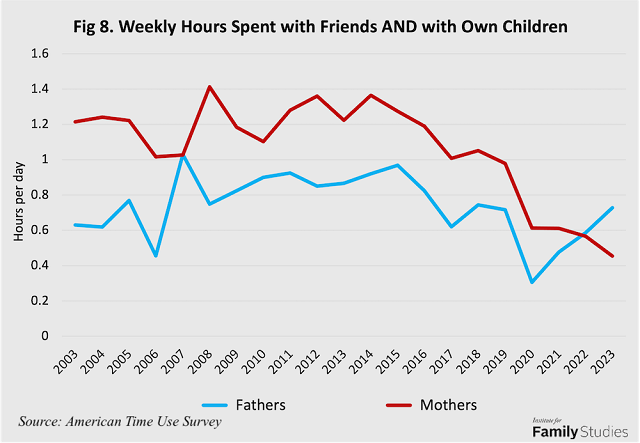

And yet, this decline in time with friends may explain why parenting feels so exhausting to so many of us. What has happened in America is that the playdate is dying. Figure 8 below shows average daily hours spent by parents simultaneously in the presence of their own children and their friends.

For mothers in particular, there has been a massive decline. Whereas in the 2000s and early 2010s, the average mom could expect to spend about 1.2 hours a week with her children and with a friend (possibly another mom), today she can only expect to spend about 30 minutes. For men, there’s been little change. As of 2023, dads seem to spend more time at playgroup than most moms.

The decline in friends-and-kids time isn’t just a product of falling time with friends in general. For dads in 2003-2006, about 15% of time they spent with friends also included their children. Today, it’s almost 25%: perhaps male friendship is becoming more child-centric even as time with friends is declining. On the other hand, for moms in 2003-2006, about 30% of their time with friends also included their children, but today it’s under 20%: women are losing their friends-with-kids supports even faster than they are losing time with friends generally.

Smartphones and Social Media?

It may be worth asking why Americans’ social time with friends has fallen so much. That this decline in time spent with friends began around 2010 or so would seem to suggest the influence of ubiquitous access to social media via smartphones. Unfortunately, ATUS has no measure of smartphone access nor social media usage, and the particularly sharp decline from 2015 or so doesn’t seem as obviously tied to when Americans were first adopting mobile access to social media. While it seems likely that the rise of digital social lives may have partly displaced real-world social lives, that doesn’t seem to be the whole story here: there’s no reason smartphones or social media should have displaced playdates for moms more than other forms of socialization.

So although the rise of constantly-online socialization probably created some headwinds for the inherently real-world nature of child socialization, that’s not the whole story. It seems that new cultural norms particularly relevant to parents (and especially moms) may have worsened the climate for parenting around 2013-2016.

So, what changed for moms in the mid-2010s? Well, the online space of mom-influencers seems like an obvious place to look. With vitriolic online debates about “gentle parenting,” gluten and anxiety, children with special needs, and the need for “free range” parenting, trad wives and more, parenting in the last decade has become inundated with branded parenting styles and strong claims about the horrible health effects of other parenting styles. The task of parenting has become more divisive and subject to judgement than ever before, and as a result, parenting together has gotten harder and less comfortable. Online social spaces feed into this process by allowing the most extreme voices to find and reinforce each other, but even parents who try to stay out of the online battle are impacted, as the friends they would otherwise have coparented with are, now, worried about exposing their child to the wrong sort of parent. And indeed, while ATUS has no measure for smartphone use, variables measuring frequency of online shopping, use of computers for leisure, or screen time generally all predict less time spent with friends, and especially less time parenting alongside friends. Google Trends data point to the rise of branded parenting styles too: terms like “gentle parenting,” “free range parenting,” or “helicopter parenting” all exploded in usage over the course of the 2010s. We became a society more divided by “parenting style” than we used to be, and so we can’t “parent together.”

Conclusion

There’s a real change afoot in American parenting, and it’s not that parents are just getting more “intense.” Rather, there have been a few major changes in parental time use.

First, moms are switching towards more focused, hands-on parenting activities, while dads are bringing their kids along to more of their lives.

Second, all Americans are seeing a dramatic diminishing of time spent with friends, with the result that parents are more relationally isolated in the past.

Third, this decline in time with friends is even more severe for moms. Increasingly, mothers are expected to leave their children behind if they want to have a social life.

Fourth, at the same time, dads are increasingly bringing their kids along when their friends are around. Nowadays, dads spend more time with their kids and friends together than moms do.

And finally, despite the rising number of old people in our society who need care, the amount of time people spend caring for elders isn’t actually rising, and in fact it has been surpassed by the ongoing dramatic increase in time spent taking care of pets.

Far from American parenting becoming more time-demanding, Americans are shedding many time-intensive ties (like friendship), reallocating time towards various kinds of experiential consumption (like pet ownership), and facing the demands of parenting more alone than ever before. Finally, perhaps in response to the increasingly lonely work of parenting, parents are increasingly thinking of their parenting in diverse, branded, technical ways, which may make it harder to coparent alongside peers who parent differently. Perhaps, then, the feeling many parents have that parenting is more difficult than ever is not due to parenting being more demanding today but to the fact that parenting is becoming lonelier than in the past.

Lyman Stone is a senior fellow and director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies. He is also the chief information officer of the consulting firm Demographic Intelligence.