Highlights

That women are waiting longer to have children, and having fewer of them to boot, is no secret. It’s also no longer a secret that women are increasingly relying on medical help to get pregnant, as the Wall Street Journal reported last week on the results of a recent Center for Disease Control & Prevention study on trends in childbearing.

The study found significant rises in the percentages of women ages 25 to 39 who relied on reproductive assistance—a broad category that includes simply seeking medical advice—to have a child. Interestingly, the numbers stayed steady for women 24 and younger and women over 40. Perhaps this is because women in these age brackets are at their most fertile and infertile life stages, respectively, and there is little that technology can do to change this.

That a growing number of women who want children are struggling to conceive is a major social failure. In a culture that is truly empowering to women, childbearing should come to take less of a physical, emotional, and psychological toll on women, not more. Yet the numbers are trending in the reverse direction (our abysmal score for maternal death and infant mortality rates for a developed nation being a whole separate discussion).

That a growing number of women who want children are struggling to conceive is a major social failure.

And assisted reproduction is no walk in the park. Any website or pamphlet on assisted reproductive treatments like hormonal treatments or in vitro fertilization (IVF) will outline a number of side effects for women ranging from mood swings, to severe weight gain, to mania. An article in the Harvard Health Letter blatantly states that infertility treatment can “exacerbate anxiety, depression, and stress,” and it cites two astounding studies that show the emotional and mental toll of infertility:

One study of 200 couples seen consecutively at a fertility clinic, for example, found that half of the women and 15% of the men said that infertility was the most upsetting experience of their lives. Another study of 488 American women who filled out a standard psychological questionnaire before undergoing a stress reduction program concluded that women with infertility felt as anxious or depressed as those diagnosed with cancer, hypertension, or recovering from a heart attack.

Why, despite these facts, are so few people talking about the impact of assisted reproduction and infertility on female flourishing?

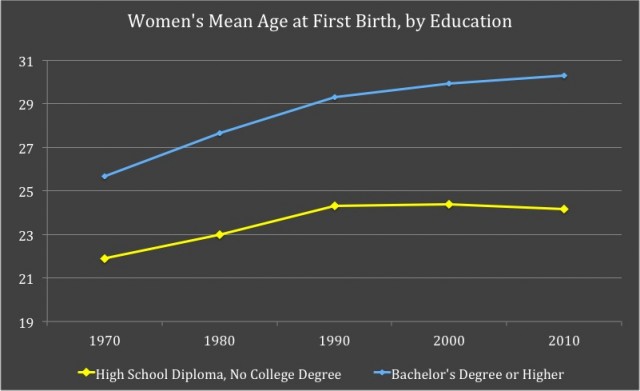

The root of rising female infertility, I would posit, is easy to identify. Women are being told, despite the plain and rather stubborn reality of female fertility, that they must delay marriage and children in order to succeed in their careers. This is especially true for women with a college degree or higher, a group that has accounted for a growing share of women over the past few decades. These women have always waited longer than other women to have children, but since 1970 the gap has widened by an additional two years. Women with a college degree now have their first child around age 30, while women with a high school diploma but no college degree first give birth around age 24.

Source: National Vital Statistics Birth Datafiles, 1970-2010

How no longer riding the dating roller coaster but instead navigating life with a supportive life partner inhibits career success is beyond me. That balancing career interests and the ever-present needs of children is tough is far clearer. Though the two are by no means mutually exclusive, even at a young age.

One other major reason women cite for delaying children is cost. This is understandable when more and more women, like men, are attaining advanced degrees that come with significant debt loads, when the cost of a college degree is soaring, and when parents are coming under increasing pressure to enroll their children in countless extracurriculars. But ironically, the longer one delays children, the more likely one is going to incur major costs in trying to conceive. The average cost for just one round of IVF, for example, is over $10,000.

Most women still want to have children. Eighty-one percent of unmarried, childless women between ages 15 and 44 say that they want to have children one day. So if we as a society are in the business of helping women, we should start by making that desire easier, safer, and less physically demanding to fulfill. And if we are being honest with ourselves, that means putting an end to encouraging delayed marriage and children.

Eighty-one percent of unmarried, childless women between ages 15 and 44 say that they want to have children one day.

Instead, we should be finding ways, through community and public policy, to support women who choose to have children at younger ages but face hurdles like significant student debt or poor childcare options. Universities, for example, would do women a favor by giving young moms the option to delay repayment of student loans during the early years of their child’s life. Workplaces could offer moms just getting on their feet a childcare bonus to help women whose earnings reflect their age. Newspapers and magazines could stop running articles encouraging women to delay children and do things like opt for harvesting and freezing their eggs.

Parents have a role to play, too. A recent study shows that today’s college students say the ideal age to get married is 25, while their parents say 26. The average college graduate marries at age 27. Rather than encouraging their daughters to wait to marry and have children, parents can help their daughters think through how to prepare to juggle children and career.

But when the overall message, especially to women in the most educated brackets, is “wait, wait, wait,” it’s only making the dreams of over three-fourths of childless women that much more elusive.