Highlights

Throughout history, marriage and parenthood have been defining milestones of adulthood. But for today’s millennial generation, these social institutions are not only loosely linked, but also beginning to lose ground.

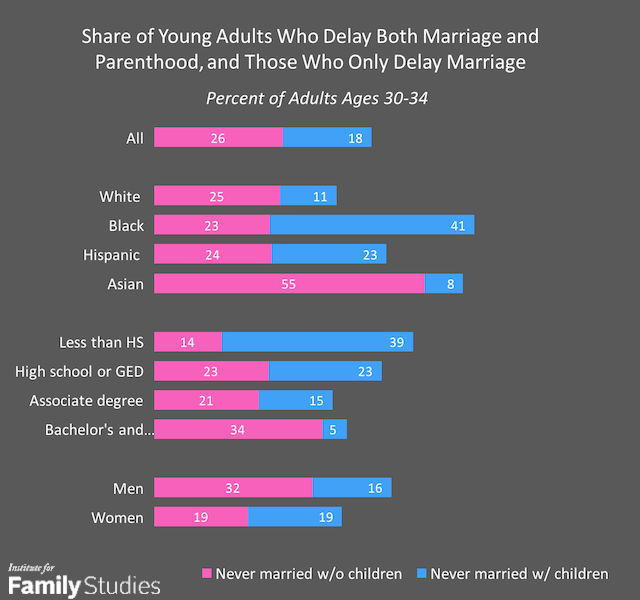

At ages 30 to 34, more than a quarter of Millennials (26%) have not yet started a family—meaning they have neither been married nor had any children, according to a new analysis of government data by the Institute of Family Studies. Another 18% of Millennials have children but have never been married. Only a narrow majority—56%—have been married before. And most of these ever-married young adults (78%) have children.

Source: IFS analysis of National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997. Note: Based on adults surveyed in 2013-14.

The group who has been married (with and without children) are included but not shown.

Millennials’ delay in “settling down” marks a clear distinction from earlier generations. When the Baby Boomers (specifically, the late cohort born between 1957 and 1962) were the same age, only 13% had not formed a family. And only 10% had never married but had children.

At the same time, Millennials’ family formation pattern fits in the bigger trend in American society today. Since 1970, the median age of first marriage in the U.S. has risen by about seven years. And the average age of first-time mothers jumped by about five years, from age 21 in 1970 to 26 in 2014.

Young adults of all groups today are postponing marriage and/or parenthood to some extent, but there is a clear divide across race/ethnicity, education, and gender. Some young adults are more likely to delay marriage but not childbearing, while others are delaying both.

Among the major racial and ethnic groups, Asian American young adults are mostly likely to delay both marriage and childbearing. In their early 30s, more than half of Asians (55%) have never been married and are childless, compared with about a quarter of young adults in other racial groups. This may be linked to the fact that Asians tend to have higher educational achievements so it takes them longer to finish their education, which delays their start of a family.

At the same time, young adults with at least a bachelor’s degree are more likely than others to delay both marriage and childbearing. About one-third of college-educated young adults ages 30 to 34 have never married or had children, compared with only 14% of their counterparts who haven’t graduated from high school. In addition, young men are more likely than young women to delay starting a family (32% vs. 19%).

In contrast, black and Hispanic young adults are more likely than others to delay only marriage but not parenthood. At ages 30 to 34, some 41% of blacks and 23% of Hispanics have never been married but have children, compared with 8% of Asians and 11% of whites. And young adults with less education are also more likely to only delay marriage but not parenthood: nearly 40% of young adults without a high school diploma had children but have never been married, compared with only 5% of young adults with at least a bachelor’s degree.

Never-married Young Adults with Children are More likely to Live with a Partner

Never-married young adults are not necessarily “single.” In fact, about one-third of never-married young adults in their early 30s (32%) live with a partner.

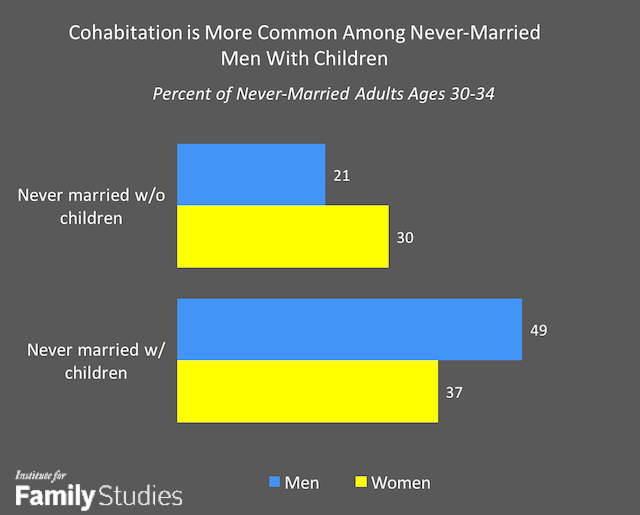

Having children is linked to a higher chance of cohabitation among these young adults. About 4-in-10 never-married parents ages 30 to 34 (43%) live with a partner, which almost doubles the share among their counterparts who do not have children (24%).

Never-married and childless women in their early 30s are more likely than their male counterparts to live with a partner (30% vs. 21%). However, the gender pattern goes the other way among never-married young adults with children. Nearly half of never-married dads ages 30 to 34 live with a partner (49%), compared with only 37% of never-married moms in the same age group.

Source: IFS analysis of National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997. Note: Based on adults surveyed in 2013-14.

The racial patterns of cohabitation among the never-married also vary by the presence of children. For example, among never-married and childless adults in their early 30s, whites (29%) are more likely than blacks (14%) or Hispanics (15%) to live with a partner. On the other hand, among never-married young adults with children, Hispanics have the highest share of cohabitation (58%), followed by whites (48%) and blacks (25%).

Never-married and Childless Young Adults are Ranked in the Middle Economically

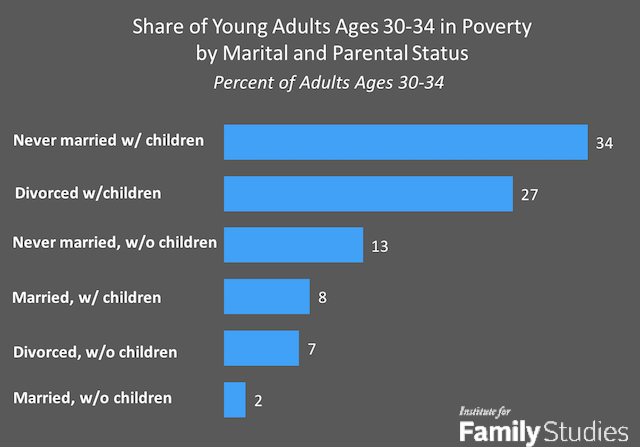

Family arrangement is often linked to financial well-being, and young adults are no exception. When ranked by the poverty rate, never-married and childless adults in their early 30s stand in the middle—13% of them are in poverty. This is slightly lower than the average rate among this age group (15%).

Never-married and childless young adults are much less likely than their counterparts who have children to be in poverty (13% vs. 34%). But financially, this group is not doing as well as married young adults. Only 2% of married young adults who delay having children are in poverty, the lowest rate of all young adults. And married young adults with children are also doing relatively well: only 8% are in poverty.

Source: IFS analysis of National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997. Note: Based on adults surveyed in 2013-14.

Cohabitation makes a difference in young adults’ financial status. Among never-married and childless young adults, those who live with a partner are much less likely than those who live by themselves to be in poverty (6% vs. 16%). Similarly, among young adults who have never been married but have children, the poverty rate of cohabiters is a lot lower than that of non-cohabiters (23% vs. 42%).

Will Today’s 30-somethings Eventually Settle Down?

No one has a crystal ball to predict the family pattern of today’s young adults. When it comes to marriage, we may get some hints from the pattern of previous generations. According to an earlier projection that I conducted at the Pew Research Center, there has been a steady increase since 1970 in the share of young adults who have never married by the time they reach ages 45 to 54. Assuming the current trend continues, when today’s never-married young adults reach their mid-40s and 50s, a quarter of them are likely to have never tied the knot.

In the case of parenthood, recent data shows that women who delay childbearing may “catch up” their fertility somewhat later in life. With the rise of birth rates for women ages 30 and older, today’s 30-something women have more babies than women in their 20s. Birth rates for unmarried women in their 30s are also rising. In 2015, unmarried women ages 30 to 34 had 60 births per 1000 people, reaching a historical record for this age group.

However, after age 35, there is a sharp decline in the birth rate. Only 34 births occurred among 1,000 unmarried women ages 35 to 39 in 2015. And birth rates for unmarried women are much lower than that of married women.

Given these demographic trends, we expect that while many of today’s 30-somethings may eventually marry and become parents, a significant share will remain unmarried and/or childless when reaching older ages. The demographic and economic divide between young adults who postpone both marriage and parenthood and those who only postpone marriage but not parenthood will further contribute to economic inequality in the United States. Moreover, the combination of delayed childbearing with the declining marriage rate is likely to lead to a steady drop of the overall fertility rate among U.S. women.

Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies and a former senior researcher at Pew Research Center, where she conducted research on marriage, gender, work, and family life in the United States.

Editor's Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.