Highlights

Editor's Note: With over 18,000 pageviews, the following research brief from Lyman Stone, which first appeared on the blog on November 11, 2021, is our fourth most popular blog of this year.

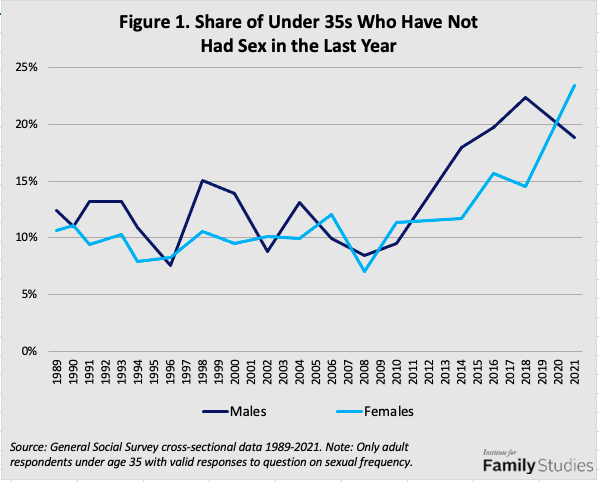

The pandemic disrupted American life in many ways, but one trend remained the same: rising sexlessness. A growing share of younger Americans are living without sex. The new 2021 General Social Survey can be used to track these trends over time. As Figure 1 below shows, since 2010, there has been a sharp rise in the share of males and females ages 18 to 35 who report not having sex in the prior year. This trend, which has been described in detail in prior IFS reports, continued in 2021.

The trends certainly have some statistical noise, and the trend began earlier for males than females, but the overall change is evident for both cases. The share of under 35-year-olds going without sex more than doubled from 2008 to 2021, from around 8% to around 21%

Some of this rise in sexlessness is driven by the broad social trend of increasingly delayed marriage. Married people are more likely to be sexually active than unmarried people: in 2021, only about 5% of ever-married people under 35 reported no sex in the past year, versus about 29% of the never-married. As a result, declining marriage tends to reduce sexual activity as married people make up a shrinking share of the population of people under 35. And indeed, in the General Social Survey data, the never-married share of under-35s rose from just over 50% in the early 1990s, to 60-75% over the last decade.

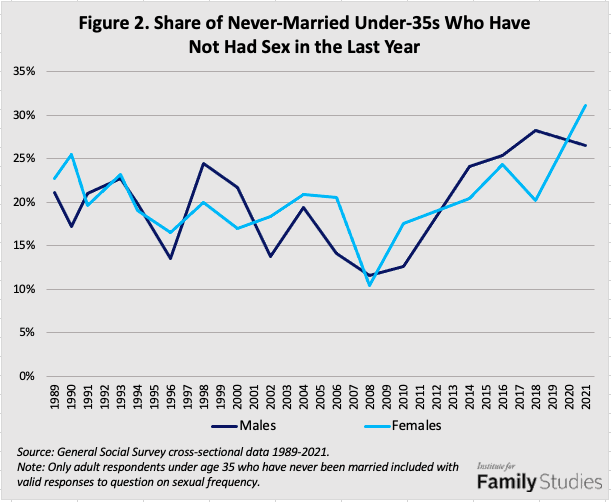

But there’s also an upward trend in sexlessness among never-married young people, albeit a slightly less pronounced one, as shown in Figure 2. While delayed marriage accounts for much of the trend of rising sexlessness, it isn’t the whole story.

Whereas sexlessness overall has about doubled since the 2000s, sexlessness among the never married has only risen from about 20% to between 25% and 30%, an increase of a quarter to half. So there have been at least two separate trends related to rising sexlessness: one is delayed marriage, and the other is rising sexlessness among the never married. That second trend is of particular interest and worth investigating further: among what groups of never-married people is sexlessness rising the most?

Unfortunately, limiting analysis to “never married people under age 35” creates very small sample sizes in the General Social Survey, and so to generate meaningful results, I combine male and female respondents into a single category. Overall trends for the two groups are similar, and most sexual activity is between males and females, so this conflation is reasonable.

Attitudes About Premarital Sex

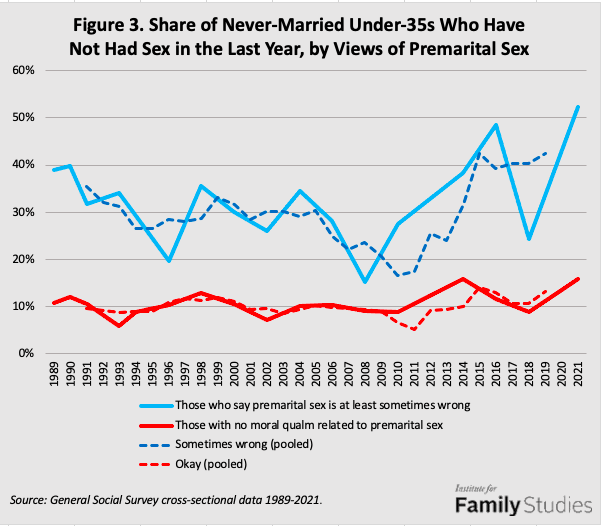

I first assess whether sexlessness has changed differently related to attitudes towards premarital sex. Some people see premarital sex as at least sometimes morally wrong, whereas other people don’t have any problem with sex before marriage in general. The GSS asks some respondents their opinions on exactly that question. Among people under 35 who have never been married, opinions of premarital sex have been fairly stable over the last 15 years, with 70% approving and 30% disapproving of premarital sex. Since any sex among never-married people is, by definition, premarital, we can expect that never-married people who say premarital sex is wrong will be more likely to be sexually abstinent than people who say premarital sex is okay.

Note: Only adult respondents under age 35 who have never been married, with valid responses

to question on sexual frequency. Pooling of year +/- 2 years to account for variable time between

waves. Premarital sex views collapsed into two categories, with those who view premarital sex as

"almost always wrong" & "wrong on some occasions" grouped & compared to those who say "not wrong."

As the figure illustrates, young adults who believe premarital sex is wrong have consistently been about two to three times as likely to be sexually abstinent for several decades (in the 2021 GSS, rates of sexual abstinence are 52% vs. 16%).

But trends over time are somewhat imprecise due to small sample sizes and statistical noise. To account for that, I also showed “pooled” estimates, which lump together all valid GSS respondents in a given year, plus respondents from one or two years before and after that year. This expands the sample size to make it a bit easier to spot durable trends. Whether pooled or not, it seems like most of the increase in sexlessness among never married under-35s has been among those who say premarital sex is at least sometimes wrong. Though it is true they are a minority of never-married individuals in this age group, their distinctive behaviors are driving the trend. In other words, much of the rise in sexlessness has been driven by people who have moral concerns about premarital sex. It might be better to call it abstinence than sexlessness, since it’s consistent with expressed values.

Pornography Use

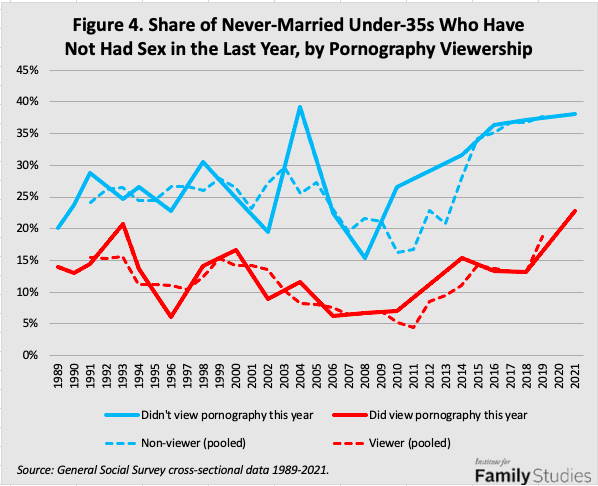

One additional component of these changes in sexual behavior can’t be ignored: pornography. The GSS asks respondents about their pornographic viewership behaviors, too. However, there’s been no major change in how likely people are to view porn among those who accept or condemn premarital sex. Across most periods, people who believe premarital sex is wrong are slightly less likely to report using pornography. Moreover, pornography use doesn’t appear to act as a substitute for sex at all. Figure 4 shows trends in sexlessness among never-married under-35s, broken out by their self-reported use of pornography in the last year.

Contrary to popular conception that pornography is replacing sexual encounters, pornography users are more likely to report having sex, and the rise in sexlessness has been similar among both pornography users and non-users. In 2021, about 23% of never-married under 35-year-olds who reported watching pornography had not had sex in the past year, versus 38% of those who did not watch pornography. So rising sexlessness is probably not closely related to pornography use, although it is the case that self-reported pornography usage has risen: the share of never-married under 35-year-olds who reported viewing porn rose from around 40% in the early 1990s, to 50% in the 2000s, to almost 60% in 2021.

Religious Behavior

One final way of breaking out the data is particularly striking and may help tie the disparate influences of sexual attitudes and behaviors together: religion. Religious service attendance is correlated with sexual behaviors and attitudes, so it may encapsulate many of the trends described above related to views of premarital sex or pornography usage. Moreover, religious worldviews and attitudes may be a key motivation for abstaining from use of pornography, holding the view that premarital sex is wrong, and abstaining from sex until marriage.

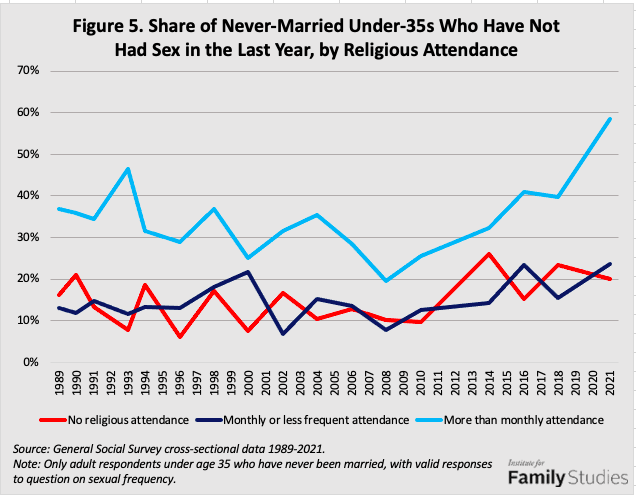

So, does religious behavior correlate with abstaining from sex? The answer is yes, as shown in Figure 5.

While there has perhaps been a modest increase in sexual abstinence among religious non-attenders or occasional attenders, the lion’s share of the increase in sexlessness has been among the relatively religiously devout. Since 2008, among never-married individuals under age 35 who attend religious services more than monthly, the rate of sexlessness has risen from about 20% to nearly 60% in 2021. Among their less religious peers, sexlessness has risen from around 10% in 2008 to 20% in 2021.

Since at the very least, most religious communities in America view premarital sex as a less preferred sexual arrangement than marriage, the increase in sexual abstinence among religious young adults could speak to an important change among religious communities. It could be that Americans who deviate from religious sexual norms are finding it harder to stay attached to religious communities as the cultural differences between religious and non-religious worlds become larger. In this scenario, as non-religious American culture becomes more sex-positive, the tension with religious norms becomes more intense, and people who deviate from those religious norms leave the church. This would imply that for many people, a key motivating factor in their religious behavior is sex.

But another explanation is that the behavior of religious people themselves is changing. Perhaps religious young adults are simply complying with the norms of their communities more determinedly than previous generations. In this scenario, we aren’t seeing religious young people change their metaphysics to validate sexual liaisons, but rather, we’re seeing religious young adults adopt more intense behavioral norms than prior generations.

In reality, both stories are probably true. Doubtless, changes in American culture writ large have made religious norms harder to square with day-to-day life for young people spending more and more years without a spouse, and some young adults have decided that the cost of compliance with religious sexual norms isn’t worth paying, as declines in church attendance may indicate. Among adults under 35 who have never been married, the share who are frequent religious attenders fell from over 30% in the early 1990s to under 20% today. But while significant, these changes in religious attendance have been far too gradual to explain the whole trend observed in sexlessness. In particular, there has been essentially zero change in religiosity among unmarried young adults in the GSS sample since 2008. So while compositional changes may matter, the behavior of religious people has changed, too. This would seem to indicate that the current generation of religious young adults is more scrupulous about avoiding premarital sex than the last generation or two.

Increasingly delayed marriage has a large and well-understood effect on sexual frequency among American adults. But the rise in sexlessness among unmarried adults is not as well understood. If the data from the General Social Survey is to be believed, a key part of this story of changing sexual behavior in America is a change among religious people, or others, who believe premarital sex is wrong. Increasingly, religious young adults are “practicing what they preach,” adopting a distinctive set of sexual behaviors. As a result, the growing diversity and polarization that typifies so much of American life is reaching even further, even into bedrooms.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.