Highlights

- Relative to people who reported having sex zero times or once per year, those who had sex up to 51 times were about a third less likely to die, and those who did it weekly or more were only about half as likely to die. Post This

- The sex-reduces-death effect is strong and clear among married people, but weak (and statistically insignificant by a mile) for the single and separated in a recent study. Post This

The more often someone has sex, the less likely he is to die. That’s the upshot of a new study published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

To study this crucial issue, the authors used data collected from 2005 through 2014 via the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and linked it to mortality records. They ended up with data on more than 10,000 people, more than 200 of whom died, a relatively big sample size.

The survey includes information about a lot of other health problems too. In running their analyses, the authors were able to control for “age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, education attainment, family poverty ratio, leisure-time physical activity, alcohol intake, BMI, smoking status, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, history of diabetes, history of [cardiovascular disease], and history of cancer,” as well as how the subjects rated their own health.

Even with all that taken into account, the differences in mortality among people with different levels of sexual activity were remarkable. Relative to people who reported having sex zero times or once per year, those who had sex up to 51 times were about a third less likely to die, and those who did it weekly or more were only about half as likely to die. Deaths from cancer and cardiovascular disease were both lower among people with higher sexual frequency.

So, what’s going on here? That’s less clear. The paper itself walks through a number of different theories that might explain the results.

Eager husbands everywhere will be tempted to interpret the effect as causal: i.e., sex itself reduces the chance of death. Don’t dismiss this out of hand. As the study notes, sex burns about 100 calories on average for men and 70 for women. Sex also releases endorphins, creating a “happy or blissful feeling” that “may be associated with better mental health and specifically enjoyment of life.” Endorphins further boost “natural killer cell activity,” which guards against infection and even cancer.

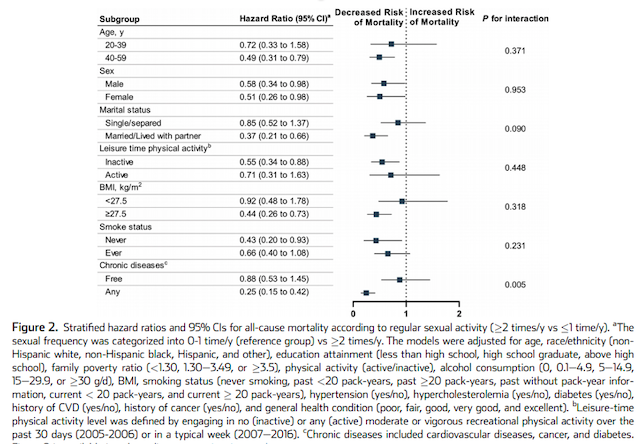

But social conservatives might prefer another possibility: High sexual frequency is largely a consequence of committed relationships, and the quality of the relationship rather than the sex itself is what reduces mortality. I think there’s at least some support for that theory in this chart, which breaks the results down for different subgroups. As the figure shows, the sex-reduces-death effect is strong and clear among married people, but weak (and statistically insignificant by a mile) for the single and separated.

Source: “Trends in Sexual Activity and Associations With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Among US Adults,”

Cao et al., The Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Technically speaking, the “P for interaction” is significant only at the 10% level, which means we can’t be too confident the effect differs by marital status. We’d need an even bigger sample to know for sure. But the difference is visually striking, and it’s at least consistent with a theory where the study is just picking up the effects of strong marriages—and where single people can’t get the same benefit by having more sex.

And of course, there’s also the most boring possibility of all: The study controls for a whole bunch of variables that measure health, but it obviously can’t control for everything that affects mortality risk, and a lot of the variables it does include are measured imprecisely. To take just one example, “leisure-time physical activity” is simply whether participants self-reported “any moderate or vigorous physical activity at leisure time,” which doesn’t include the exercise people get from paid work or housework. Further, the authors themselves note that “early symptoms of diseases may predict a decline in sexual activity before the diagnosis of the condition.”

Despite the complicated modeling, in other words, the study could just be picking up the fact that healthier people are more sexually active. Yawn.

One last note: In a separate analysis using NHANES data through 2016, the authors investigate whether people are having less sex than they were in the mid-2000s. Their results here are small and statistically insignificant, and they conclude that “the prevalence of sexual activity . . . was stable among US adults aged 20-59 years.” It’s worth pointing out, though, that IFS’s Lyman Stone has found a decline specifically among young men in numerous data sets, including NHANES itself.

Anyhow, as for whether sex saves lives, I would guess all these theories contribute at least something: Sex boosts health by itself, committed relationships are good for your health and also involve lots of sex, and healthy people have more sex even above and beyond what’s accounted for in the study’s controls.