Highlights

- Some parents will always choose not to use center-based care, and even as child care programs seek to expand access to center-based care, the same level of support needs to be afforded to children who are raised at home. Post This

- Poor families are far less likely to enroll their kids in child care than middle-class and wealthier families. Post This

- The state may have an interest in giving parents more ability to choose different child care options, but the state has no grounds to decide that parents themselves are disfavored (i.e. less-subsidized) for the care of their own kids. Post This

President Biden has proposed an increase in spending on day care and early childhood education by hundreds of billions of dollars through a range of different programs. Exact legislative language isn’t available yet for all items in the proposal, so it’s not possible to say exactly what this plan would do in practice. But there are several key principles that should guide policymakers as we debate child care policies and the increase in spending in this area: choice, compensation, fairness, and cost.

1. Choice

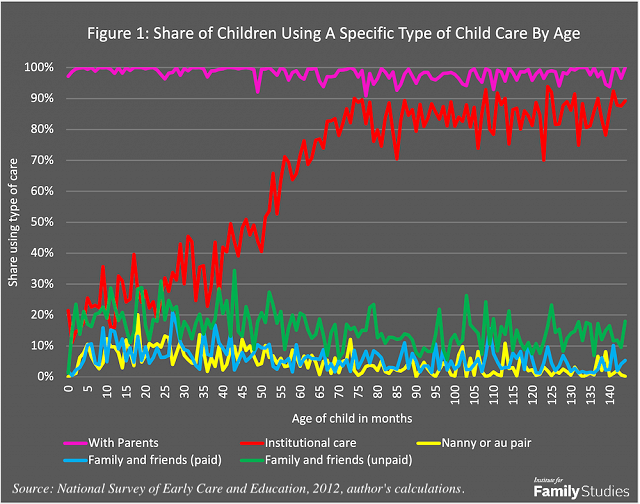

Any new spending should give parents more choice about child care, not less, and correspondingly should not discriminate between different parental choices. According to the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education, the graph below shows what share of kids at each month of age receive any child care in each of the listed settings.

It is not until about 50 months old that a majority of children are enrolled in center-based care (or public education), and enrollment in these environments never exceeds 90% of children. Which is to say, even for children at ages where there is universal freely provided public education and laws compelling a certain level of education, nearly one in 10 children apparently won’t be enrolled anywhere at all (though some other sources, like the Current Population Survey, put the figure closer to 5%). For early childhood care, where presumably attendance will not be mandatory, enrollment rates will almost certainly never reach 90%, meaning the number of children outside of the formal care system will always be very large.

Some parents will always choose not to use center-based care, and even as child care programs seek to expand access to center-based care, the same level of support needs to be afforded to children who are raised at home. Otherwise, parents are not being afforded a fair choice: they can either receive tens of thousands of dollars of state support for free child care, or keep their child at home and receive nothing. Were the state offering tens of thousands of dollars in extra subsidies to people of a specific race, sex, or religion, we would understandably see this as discrimination even if it contained no extra penalty for the disfavored group. It’s no different for parental choice: the state may have an interest in giving parents more ability to choose different child care options, but the state has no grounds to decide that parents themselves are a disfavored (i.e. less-subsidized) option for the care of their own kids.

Some might argue that this criticism is baseless because we don’t give homeschoolers a subsidy equal to public school spending. To this there are two major replies. First, we really should do more to support school choice by providing vouchers to families. Indeed, most people recognize that the public educational system in America is underperforming versus our international peers, so emulating our broken, hyper-conformist school system is not a very compelling argument.

Supporting only center-based care puts a heavy thumb on the scale against parental child care provision despite the fact that there is no reason for the state to believe center-based care is better.

Second, there are good reasons to impose some limits on school choice, especially at higher grade levels. Schooling often involves topics parents aren’t qualified to teach (as many learned during the remote schooling months of COVID), and so it is very inefficient to provide homeschooling for the majority of kids; parents may often struggle even to identify suitable online courses or curricula in subjects they can’t teach their kids. But parents absolutely can teach a baby to walk or identify colors. Schooling also often has curricular components that are widely agreed upon as necessary for functioning in modern society (like basic literacy and arithmetic). When there are disagreements about the curriculum for public education, they are often rancorous and divisive precisely because the fundamental justification for public education is that some neutral, agreed-upon curriculum exists. But there are deep philosophical debates among early childhood experts about whether it makes sense to have a curricular approach to caring for a 3-year-old, and the vast majority of what young children learn occurs through emulation and osmosis. To a great extent, the things young children learn are either biological universals (how to walk), cultural traits (parental language and accent, religious rituals), or some mixture of both (how to use the toilet: squatting or sitting?). These are things that virtually anyone is qualified to teach but parents are uniquely positioned to teach. And indeed, when Germany expanded its public child care system, linguistic minorities systematically refused to participate, perhaps because they wanted to preserve their within-family practices of cultural transmission.

In other words, any child care system that is going to expand and empower parental choice will have to do more than just subsidize day care. It will also have to subsidize care at home. This isn’t some controversial right-wing talking point: Norway, Sweden, and Finland all provide some type of at-home child care allowance. These allowances are disproportionately used by parents who are linguistic or cultural minorities, precisely for the reasons outlined above: childcare is about cultural formation, and so cultural minorities tend to opt-out.

2. Compensation

Child care work is important, and so it deserves appropriate pay. On average, according to the Current Population Survey, workers in the child care industry get paid about $12 per hour. Workers in all other industries combined (including salaried workers) earn about $31 per hour. So child care workers make just over 1/3 of what other workers make. On its face, this seems egregious.

But there are several complicating factors. First, child care workers generally work fewer hours: 35 a week vs. 39. In general, jobs with shorter workweeks or more flexibility (such as part-time options or job-sharing) pay lower hourly wages. Put another way, because a lot of people would prefer to work a shorter week, employers can trade off “job quality” (i.e., fewer total work hours) for “hourly wages.” The reality is, long-hours jobs tend to have higher wages-per-hour, and child care work tends to require less time on the job.

Second, center-based care has more regular hours. Parents generally want predictable child care, and it’s rare (although not impossible) to have day cares open at 11 at night or 5 in the morning. Compared to other sectors, child care workers have more predictability and regularity in their work schedule

Third, child care work is work that many people want to do. This is not to say it is easy! But the share of the population that derives personal satisfaction from caring for children is much larger than the share of the population that derives those feelings from, say, filling out an inventory sheet or stacking boxes. Because child care work offers relatively high “intrinsic rewards,” employers can always find workers who will work for relatively low wages.

The reality is that the inequality in wages between child care jobs and other jobs is largely due to features inherent to the industry.

None of this is to say child care workers should not be paid more, but it is to suggest that the forces keeping workers’ wages low are extremely hard to combat. There are a lot of what economists call “compensating differentials” in child care work that mean there are a lot of potential workers out there who will accept a job at a relatively low wage. If we set a minimum wage for child care workers at $15/hr, it’s likely employers would trade off on benefits, or else have a lower threshold for firing workers, since finding replacements at that wage rate would be comparatively easy.

Indeed, there’s empirical proof that this wage gap for child care workers is probably very hard to solve. In 1983, the earliest data I have, non-childcare workers earned, on average, 152% more per hour than childcare workers. In 2019, the difference was still 152%. There have been years when the ratio was larger or smaller, but the key point is that despite numerous changes in labor policy, minimum wages, and government supports, the ratio between child care wages and non-childcare worker wages has been pretty stable. The reality is that the inequality in wages between child care jobs and other jobs is largely due to features inherent to the industry.

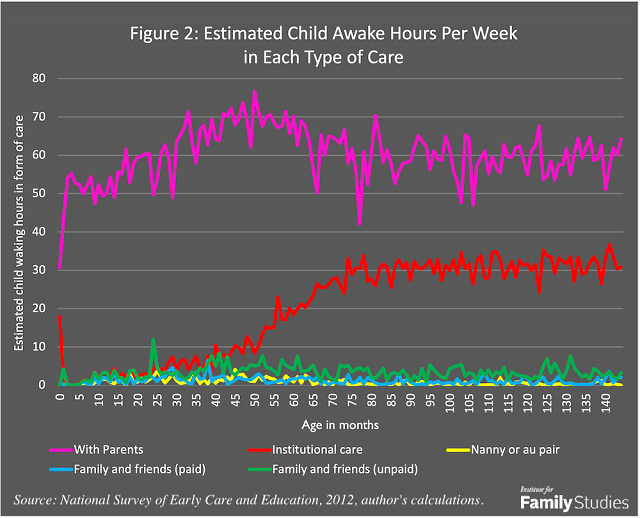

More to the point, these factors only apply to employees in child care. Parents who care for their own child at home get even lower wages. A day care worker might watch anywhere from 2 to 8 kids depending on age, making his or her per-child hourly wage somewhere between $1.50 and $6.25 per child, per hour. But using the same survey as before, we can estimate how many hours of care parents provide (note, I did not include hours when children were likely sleeping). The figure below shows the average hours of care provided by each type of care provider, by age of children in months.

All cash transfers directly to parents simply for having children under President Biden’s newly-generous child tax credit of $3,600 per child under 6 amount to $14,400 before age 4. Those parents’ total hours of caring for that child likely add up to about 12,400 hours. This means that, right now, the average parent is being compensated about $1.15 per hour for caring for a child between birth and age 4; and remember, I’m excluding the child’s sleeping hours here. So parents caring for their kids at home are compensated at about 1/6 to 2/3 the rate of child care workers under Biden’s current plan (it was even worse under prior policies, of course). However, this isn’t a fair comparison: families get this subsidy whether they use child care or not.

Now imagine that the government announces a subsidy for child care worth $20,800, the amount of money the Center for American Progress says it costs to provide high quality child care for toddlers for a year. That same report says that for that age group, 62% of the cost is labor. So that tells us how much money is going directly to subsidize labor: $12,896. That’s the size of the benefit the government would need to provide parents, per child, to make the decision between day care and at-home care financially fair. Anything less is discriminating against at-home care, which means largely discriminating against poorer families from ethnic, linguistic, and religious minorities.

Needless to say, thus far, no Democrats have actually proposed an at-home care allowance of that kind.

3. Fairness

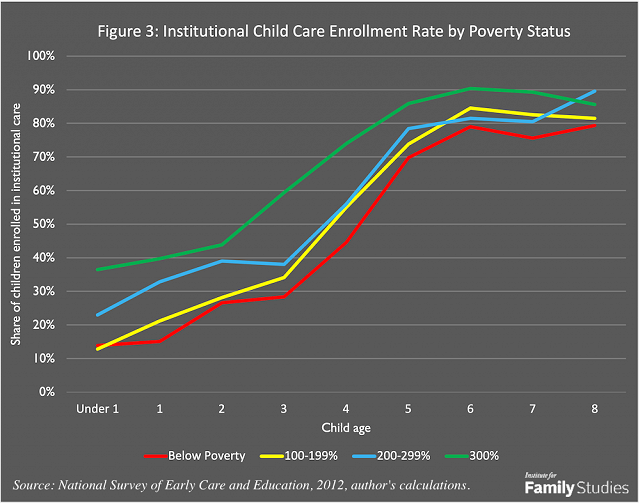

Any policy will necessarily have to confront difficult questions about who uses what type of care and why, and how to be fair to people who make different choices. I have at several points noted that who uses child care is not exactly random, but it’s worth getting more explicit. First, again using data from the NSECE, we can compare the income and poverty status of kids in center-based care to other kids. Here’s the share of kids who are in center-based care or school, by child’s age, based on household poverty status.

As this figure illustrates, the odds a kid is enrolled in center-based care vary widely based on family income. Poor families are far less likely to enroll their kids in child care than middle-class and wealthier families.

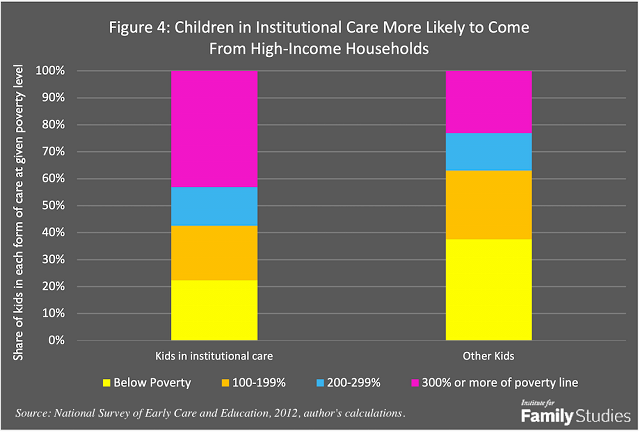

Another way to look at this is to ask, when child care transfers to kids are made, what share of them go to poor families vs. high-income families? The figure below provides an answer to this question.

Of kids in formal care, just 22% are from families below the poverty line, and a solid majority of kids are coming from families with incomes at 200% of the poverty line or higher. Among kids who are not in day care, the proportion flips: 38% are below poverty, and a majority are below 200% of the poverty line. In other words, kids at day care are overwhelmingly more likely to be well-to-do kids, and kids being raised at home tend to come from poorer families.

To ensure basic fairness and neutrality across cultural lifestyle preferences, any child care policy should include an at-home care allowance.

However, this isn’t persuasive to many people, because there’s an obvious reason that child care usage rates would vary in this way: higher-income families can afford child care, while poorer families can’t. Wouldn’t making child care free alleviate these gaps?

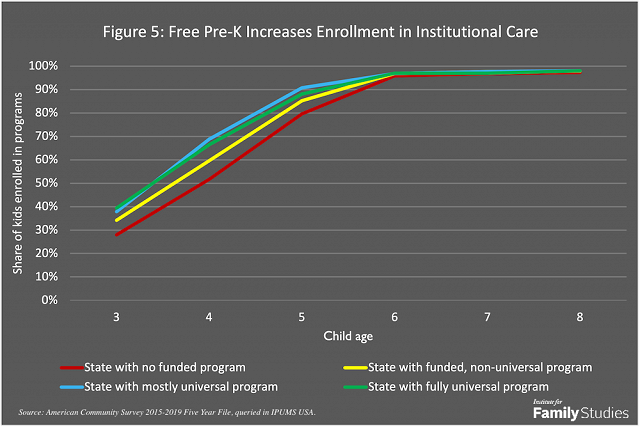

Probably not. Unfortunately, the NSECE does not provide state-level data to compare states with free child care programs to other states. But the American Community Survey does provide state-level data, as well as estimates of the share of 3- and 4-year-olds enrolled in any formal program of the kind that Democrats propose to expand. By comparing states with free, universal pre-K to other states, we can determine if making child care free increases enrollment or changes the income mix of who attends. To identify which states have free early childhood education programs, I used a recent report from the Education Commission of the States.

States with free, universal programs do see higher shares of kids enrolled in those programs at early ages. In general, the difference between states with no funded program at all and states with fully- or mostly-universal programs is about 10- to 20-percentage points of the child population being enrolled. This is a big effect.

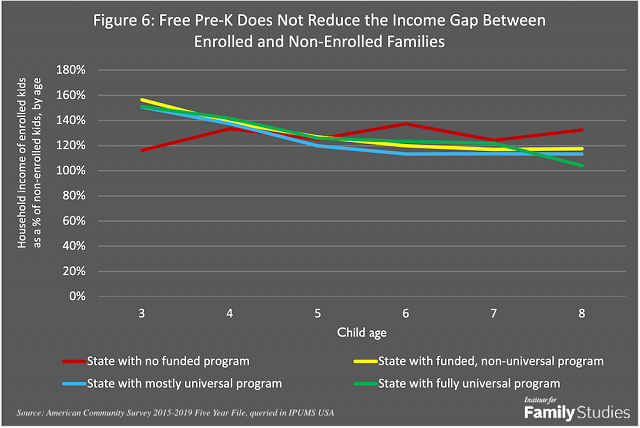

But does it change the income gap in who enrolls? Here, the answer is no. Here’s the ratio of average household incomes between kids in institutional care and kids not in such care.

States with no program constitute a small sample size, so their trend may not be reliably estimated. But if anything, it looks like free and universal pre-K makes the income ratio worse, not better. More likely, it has no effect at all. When pre-K is free, enrollments do rise, but they rise as much among high-income as low-income families, with the result that high-income families remain over-represented among day care users. This effect continues even beyond mandatory schooling ages: homeschooling families tend to be poorer than other families.

In other words, subsidies for child care disproportionately go to high-income families even when programs are totally free and universally accessible. The cause of the mismatch is not that poor families just cannot afford child care, but that poor families have lower demand for it. There are many reasons for this. For example, poor families include cultural minorities who may desire to take a more active hand in their child’s cultural formation. It’s also possible that how much people enjoy caring for children is correlated with income: high-earning people might derive less satisfaction from doing more child care.

But a more likely explanation is that poor families tend to have bad work options. Even if child care is free, if their best work option is a low-wage job with unpredictable scheduling and poor working conditions, many of these parents may view staying home with their child as a preferable option. A parent who is thinking about their child’s long-term future might conclude that child is better off in a lower-income family where one parent provides full-time care instead of in a subsidized day care program.

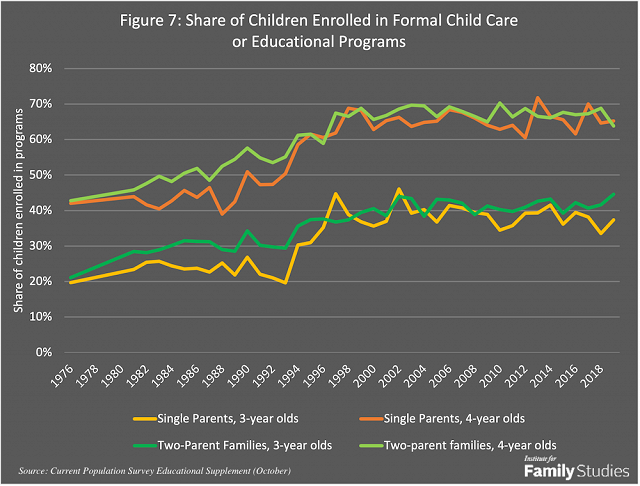

The influence of work policies on child care is easy to demonstrate in one important natural experiment: welfare reform. From the mid-1990s until the early 2000s, states and the federal government changed numerous policies to encourage work more and discourage welfare dependency. As part of this, subsidies for child care increased, but the “returns to work” were also dramatically increased for low-wage workers. These changes mostly impacted single parents, who made up a disproportionate share of the welfare rolls. The figure below shows the share of 3- and 4-year-olds enrolled in any formal education by whether they were in a one-parent or two-parent household.

Welfare reform used a combination of work subsidies like the EITC alongside work requirements to increase the returns to work for low-income women especially, even as direct support for work-related child care was increased. Welfare reform was very successful at boosting labor force participation among low-income moms, and in the process, it doubled the share of single parents’ young children who were enrolled in center-based care.

This was a victory for the economically conservative goal of getting poor moms off welfare rolls and into the workforce, but it was perhaps a defeat for social conservatives who would like to see more parental involvement in children’s lives. And indeed, two recent studies have shown that welfare reform decreased parental engagement in children’s lives and led to more emotional distance between parents and kids, with the result that children’s behavioral and schooling outcomes deteriorated appreciably. Nor is this just an issue in the U.S.: in Quebec, childcare expansions caused a significant increase in behavioral problems among enrolled kids, and ultimately an increase in crime.

4. Costs

Finally, there’s the issue of cost. The Consumer Price Index indicates that child care prices have risen 214% since 1990, the earliest data available. This is far above the general inflation rate, and one of the higher inflation rates of any sector, right up there with college tuition and complex medical procedures. This isn’t just because of rising wages for child care workers; the increase in childcare worker wages (189%) has been somewhat less than the overall price trend, and has been about the same as other workers (174%). Indeed, payroll’s share of costs for the child care industry was basically unchanged from 1997-2012, even though parental spending-per-hour-of-care rose by at least 30% from 1990 to 2011 in real, inflation-adjusted terms.

Child care represents a kind of perfect storm of cost-drivers.

So what’s happening? Well, the likeliest drivers relate to the fundamental problems facing childcare. Throughout the economy, nominal wages rose. But in many sectors, workers got more productive. One worker in a car factory can make more cars per hour today than 30 years ago. But this isn’t the case with child care. One child care worker today has the same number of eyes and hands and ability to wrangle kids as 30 years ago. So child care centers compete to hire workers against sectors with much greater productivity growth. That’s why wage growth has been about the same in the child care sector as in other industries: because wage growth across sectors is always highly correlated in the long run. This phenomenon is called “Baumol’s cost disease,” and is well-known among labor economists.

But it gets worse: you can’t just ramp up production of “child care services” by hiring more workers. It’s not like you can just run your childcare center for more hours of the day; most parents aren’t itching to hire child care from 9 PM to 3 AM. Nor can you just cram more kids into the same space. Thus, as productivity growth throughout the economy outpaces productivity growth in child care, labor-costs-per-hour-of-care rise; but as total labor demanded rises, this creates an almost exactly proportional increase in demand for physical space for child care. And child care space is complicated: child care providers face extensive regulations about what kinds of space they can use, and beyond that, even if use were totally unregulated, parents prefer certain uses of space. For example, kids need some sunlight and a space for outside play without the threat of getting hit by a car. So child care centers often have to shell out for ground-level real estate with fenced-in space for a playground. That is extraordinarily expensive to do in a society with increasing real estate costs, urbanization, and strict land use regulations. Some municipalities even use their zoning codes to prohibit child care centers from opening up on cheap real estate. So child care providers not only face the challenge of Baumol’s cost disease, they also face a real estate problem similar to what first-time homebuyers face.

To make matters worse, well-intentioned efforts to improve child care quality sometimes backfire. Regulations that require educational certifications for child care workers dramatically reduce the number of providers in an area, restricting supply and possibly increasing cost. Free child care programs sometimes even cause downstream cost increases in other areas.

In other words, child care represents a kind of perfect storm of cost-drivers. A financial commitment big enough to provide free care for every child in America today won’t even cover half of them 20 years from now, even in inflation-adjusted terms. Policymakers could help families more by tackling the factors driving cost growth rather than simply throwing good money at a bad system.

Conclusion

America’s child care system is deeply flawed, phenomenally expensive, and access is often limited to the wealthiest families. Lack of access to affordable child care has negative effects for many families, and many families don’t have real choice about how to balance their various responsibilities. For all these reasons, it’s good that child care is getting more policy attention.

But as we have this debate, we must be clear about what child care is: a program disproportionately used by well-off people to enable a specific cultural preference. The main reasons people use or don’t use child care relate to attitudes about childrearing and outside wage-earning options, not necessarily the cost of care itself, and so increased subsidies will mostly benefit current users who are disproportionately well-off. Moreover, supporting only center-based care puts a heavy thumb on the scale against parental child care provision despite the fact that there is no reason for the state to believe center-based care is better.

To ensure basic fairness and neutrality across cultural lifestyle preferences, any child care policy should include an at-home care allowance. Sure, such an allowance would dramatically increase the CBO score for a piece of legislation, but that is hardly the worst cost-related problem related to subsidized child care. Spiraling labor, land, and regulatory costs are making child care increasingly unaffordable for most parents at any level. Without concerted action to contain costs, any subsidy proposal will become a massive and ever-growing financial drain, even as access remains elusive.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was formerly a market forecaster for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.