Highlights

“Sexist.” “Bigot.” “Offensive.” These are the words of choice for public figures—from Tucker Carlson to Erick Erickson—who have the temerity to argue that men’s breadwinning still matters in contemporary families. A recent Washington Post article by Erik Wemple, for instance, called Carlson a “sexist,” in part, for pursuing this line of questioning: “Are female breadwinners a recipe for disharmony within the home?” And a few years ago, Megyn Kelly rebuked Erick Erickson for advancing the view that male breadwinning is better.

One challenge with ruling this kind of argument out of bounds is that it overlooks research in social science on male breadwinning and contemporary marriages. Today, men still earn the majority of the income in most married-parent families. A study by University of Chicago economist Marianne Bertrand and her colleagues found that husbands and wives were less likely to report a “very happy” marriage when the wife earned more; they were also more likely to report marital difficulties in the last year. A recent Pew survey found that never-married women are much more likely to report that finding a spouse or partner with a “steady job” is “very important” to them. Not surprisingly, a new study found that “the tendency for women to marry men with higher incomes has persisted.”

Clearly, the ideal and the reality of male breadwinning remain alive, at least in some quarters. However, some, such as Richard Reeves, the co-director of the Center on Children and Families at Brookings, have argued that the traditional model is less likely to characterize the marriages and family lives of more educated and affluent Americans. He suggests, for instance, that marriage among the well-educated is less likely to be predicated on male breadwinning.

While Reeves is certainly right to note that the college-educated are more likely to embrace “egalitarian ideals” of marriage and family life, when it comes to the behavior of more educated Americans, the reality is more complicated. Looking specifically at patterns of marriage, it looks like male breadwinning lives on. To examine this issue, I investigated the relationship between the share of individuals above age 15 who are married (“marriage share”) and measures of male breadwinning, which I proxy using the percent difference between male-female labor income (“earnings”) and employment using Census Bureau tract-level data from 2000 to 2015. Another way to think about this is: Are Americans more likely to be married in communities where men are earning or working relatively more than women?

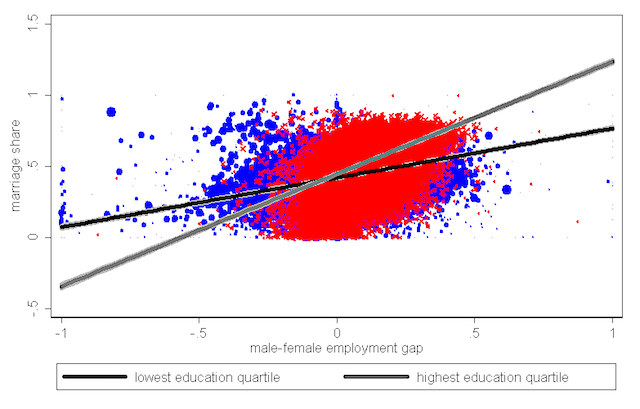

I found that areas with a higher male-female employment gap—that is, the percent extra of employed males, relative to employed females—have greater shares of the local population who are married. For example, Figure 1 (below) plots the relationship separately for tracts with the least and greatest share of college or graduate degree workers.

The data shows that a one percentage point rise in the male-female employment gap is associated with a 0.347 percent rise in the share of married adults for the areas with the lowest fraction of college or graduate degree workers, but is associated with a 0.79 percent rise for the areas with the highest fraction of college or graduate degree workers.

Figure 1: Male-Female Employment Gap and Marriage Share, Across Tracts (2000-2015)

Source: Decennial Census and American Community Survey accessed through SocialExplorer. The figure plots the share of individuals above age 15 who are married with the male-female employment gap at the tract-level for tracts in the first (blue dots, black line) and fourth (red dots, gray line) quartiles of college attainment (the fraction of individuals with a college degree or more). Each observation is weighted by its total population.

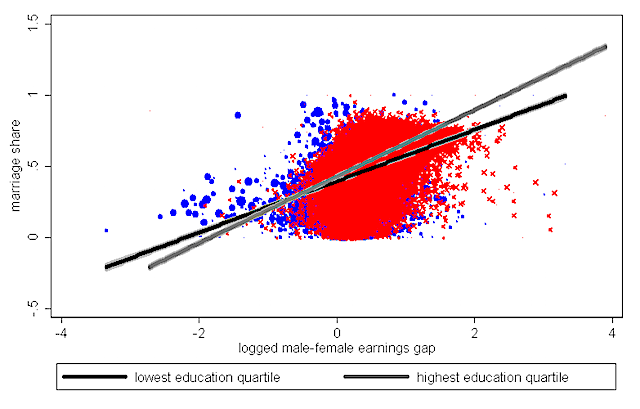

The results are very similar when using the male-female earnings gap as the proxy for male breadwinning: a one percentage point rise in the male-female earnings gap is associated with a 0.18 percent point rise in the share of married adults in the least educated areas, but with a 0.233 percent rise in the most educated (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Male-Female Earnings Gap and Marriage Share, Across Tracts (2000-2015)

Source: Decennial Census and American Community Survey accessed through SocialExplorer. The figure plots the share of individuals above age 15 who are married with the male-female logged earnings gap (wages and salaries) at the tract-level for tracts in the first (blue dots, black line) and fourth (red dots, gray line) quartiles of college attainment (the fraction of individuals with a college degree or more). Each observation is weighted by its total population.

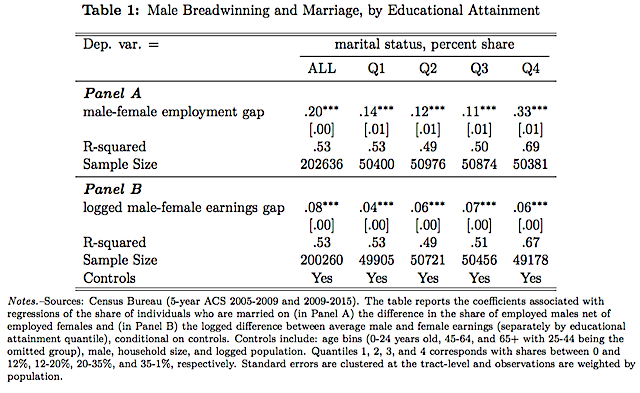

Are these differences due to other demographic factors that are spuriously correlated with marriage rates? To examine this, I separately regress the share of married adults on the two proxy variables of male breadwinning, controlling for the age, race, and household size distributions across tracts over time. Table 1 (below) documents these results. Increases in both the male-female employment and earnings gaps are associated with robust increases in the share of married adults. And what’s especially important is that the gradient is largest for tracts with the greatest share of college or graduate workers and lowest for the tracts with the lowest share. For example, in the fourth quartile, a one percentage point rise in the male-female employment gap is associated with a 0.33 percentage point rise in the share of married adults, whereas it is only associated with a 0.14 percentage point increase in the bottom quartile.

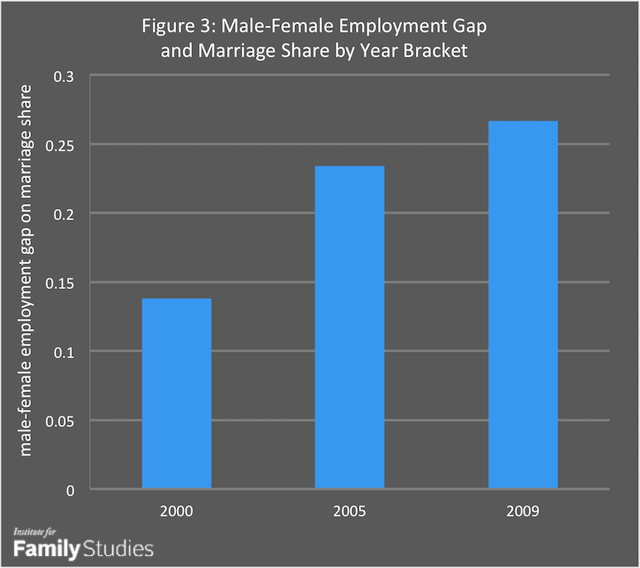

Furthermore, the relationship intensified during the Great Recession. For example, Figure 3 (below) regresses the share of married adults on the male-female employment gap separately by five-year intervals. If anything, the gradient between marriage and breadwinning appears to be growing more, not less, important. Moreover, given that the rise is consistent since 2000, the presence of the Great Recession does not seem to invalidate this relationship. Indeed, the Great Recession may have had a disparate impact on marriage in communities hit hardest by men’s job losses.

Source: Decennial Census and American Community Survey accessed through SocialExplorer. The figure plots the share of individuals above age 15 who are married with the male-female employment gap at the tract-level separately by year bracket. Controls include: age bins (0-24 years old, 45-64, and 65+ with 25-44 being the omitted group), male, household size, and logged population. Each observation is weighted by its total population.

What does this data tell us? The idea that male breadwinning is less important for marriage in more educated communities, as Richard Reeves has argued, may sound good in theory. But in reality, it looks like male breadwinning is perhaps even more important in better-educated communities than it is in the nation as a whole.

To be sure, this analysis is correlational, so we cannot be certain of the direction of causation here. This relationship may be explained in part by the fact that men tend to work harder and more successfully after they marry. But what is clear is this: In the United States as a whole, and especially in better-educated communities, when men earn more and work more relative to the women in those communities, a greater share of the local population is married. These findings suggest we should be more cautious and humble before accusing those who are concerned about male breadwinning and marriage of being sexists or bigots.

Christos Makridis is earning doctorates in both economics and management science & engineering at Stanford University.